In two previous articles on ‘Don’t Pay’ and ‘Enough is enough’ we stressed the importance of collaboration between workers in companies like British Gas or electricity providers with initiatives that struggle against energy price inflation.

The following translation describes the work of the autonomous committee of workers at the electricity company ENEL in Rome in the 1970s. There are three main aspects that we find particularly important for the situation in the UK today: firstly, the workers at ENEL managed to organise themselves independently from the trade unions and developed their own effective form of strikes, something that was missing in recent disputes, first of all during the strike at British Gas in 2021; secondly; the fact that some members of the autonomous committee were employed as technicians and engineers in the nuclear power and research department meant that they were able to criticise from a workers-scientific point of view the class character of the state’s development plan, which was supported from all so-called ‘progressive forces’, such as the Communist Party PCI; thirdly, the inside knowledge of the ENEL workers facilitated the widespread campaign of reducing the electricity bills and allowed the workers to sabotage the companies’ attempt to cut peoples’ electricity supply.

The committee at ENEL was part of a wider communist association, which organised itself around the Autonomous Workers’ Committee in Via dei Volsci. Part of this association were 13 neighbourhood committees, involved in housing and antifascist struggles, and workers’ committees at the university clinic, the railways, the telephone company SIP, at several factories and on building sites. These types of communist committees existed in most larger cities, with strongholds at factories like Magneti Marelli, and there were various attempts to forge the committees into a new political organisation, amongst others through the project of Senza Tregua. We still see these experiences as a major reference point for us today.

We have translated the following passages from ‘Working class autonomy in Rome’, by Giorgio Ferrari and Marco D’Ubaldo. It starts with a bit of general background on CAO in Via dei Volsci and then look at the ENEL committee and the struggle for autoreduction.

Via dei Volsci – a road and a history

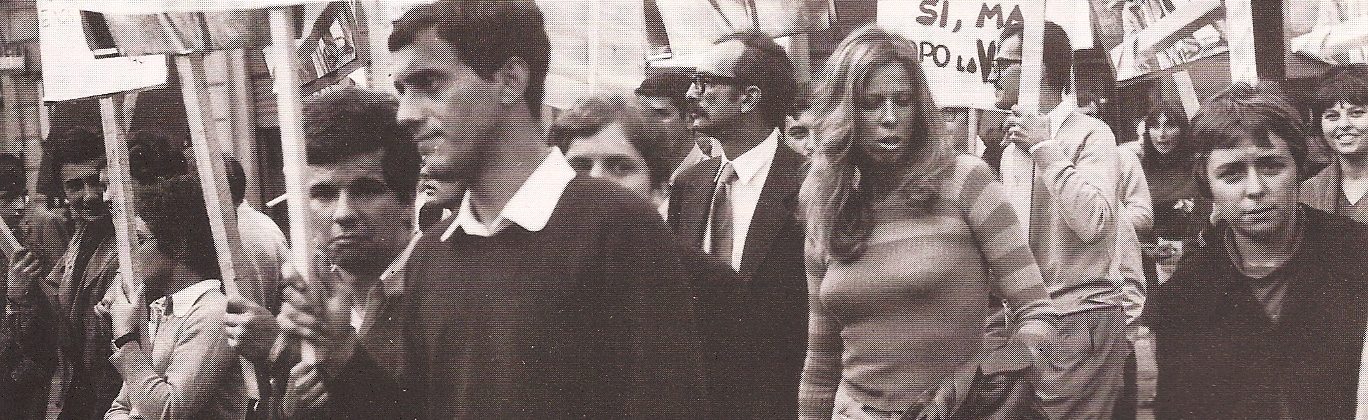

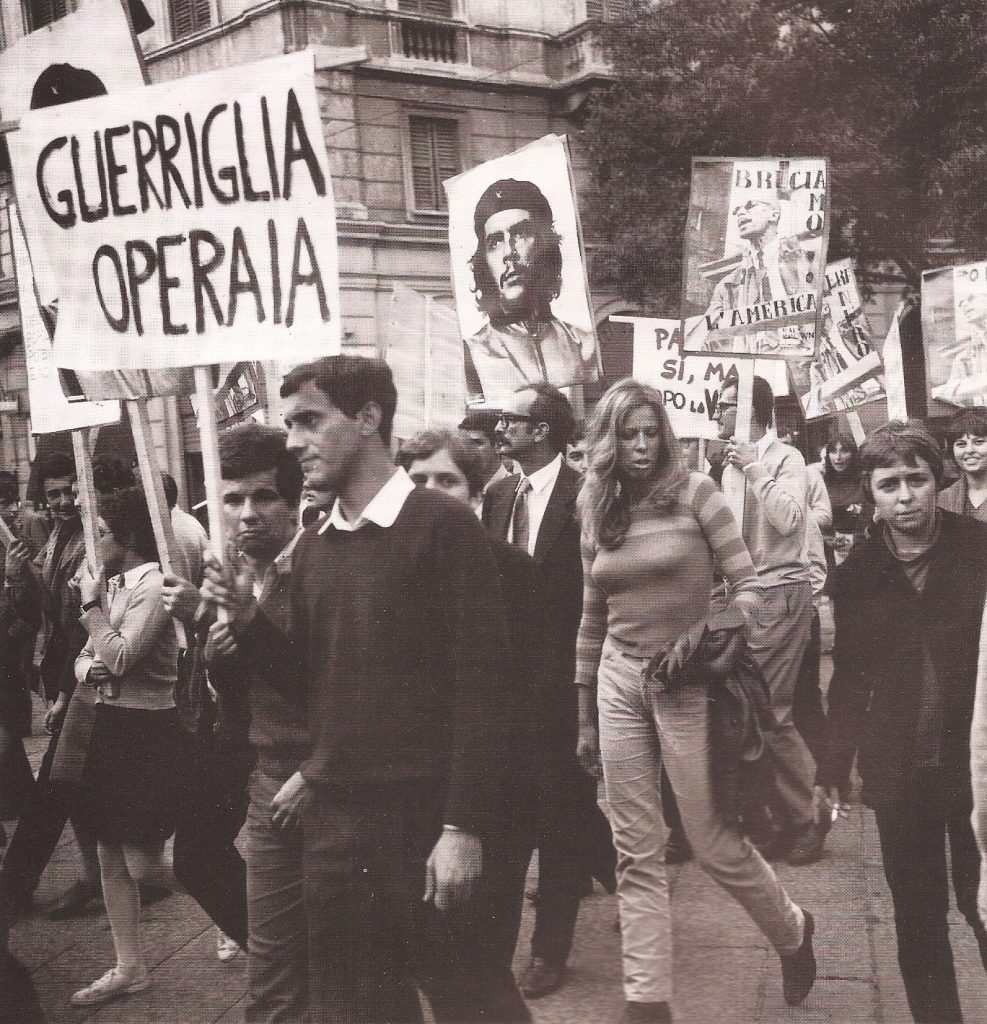

We had grown. Other collectives and committees in Rome and its hinterland had joined the initial group of comrades who left Manifesto in 1972. In three years, from 1973 to 1976, the number of collectives had practically doubled and now covered various neighbourhoods – from Monteverde to Valmelaina, from Primavalle to Tuscolano, from San Lorenzo stretching to Ostia, Tivoli and Castelli Romani. Thus, when the political meeting place in Via Volsci became a reference point, all the groups of the extra-parliamentarian left were part of the political situation in Rome, even though the political representation was still solidly in the hands of the Communist Party of Italy (PCI).

The hegemony of the PCI and trade unions was only questioned in a few areas of the service sector. The rank-and-file organisation CUB practiced hard forms of struggle in the railways, in disagreement with the mainstream unions CGIL-CISL-UIL. The CUB repeatedly caused the train station Roma Termini to come to a complete standstill. At the SIP (the new national corporation for the telephone service) there was a consistent and active core group of workers. In the health service, the Collective of Workers and Students at the Polyclinic was a reference point, while the Political Committee at ENEL (Ente nazionale per l’energia elettrica, National Electricity Board) was present in the electrical utilities sector.

With the exception of a few students who were active in the Collective at the polyclinic (and who played a fundamental role in the development of the struggle), these organisations were exclusively formed by workers: office workers, technicians, employees in the administration, manual workers. Workers, indeed. Wearing the scrubs of the nurse, the porters’ uniform or the boiler suit of the ENEL electrical supplier, these workers were part of the exploited workforce, like those working in factories – even though they might not have had the ‘stigma’ of calloused hands. It was a characteristic trait of the comrades of Via Volsci that they drew attention to the movements of these workers, who were otherwise snubbed by the ‘official authorities’ of the working class, as if they were unproductive or parasites, and, in any case, only seen as marginal when it comes to the interpretation of the conflict between capital and labour.

There was no other political organisation in Rome that had such a composition of militants, which set it apart from other experiences of the extra-parliamentarian left. However, it was not easy to gain acceptance of this diversity, which was also a diversity of language and behaviour.

The Political Committee at the ENEL

The Political Committee acted within the national electricity board ENEL. The Commitee was initially linked to the Manifesto group and formed out of the struggle led by some departments around the issue of work organisation. The structure of ENEL was composed of many different segments that reflected the diverse aspects of a productive cycle requiring multidisciplinary knowledge and elevated levels of specialisation corresponding to groups of workers of multiple professions. But the totality of the productive process, which was integrated by nature, meant that this composition of the workforce was constantly influenced by the activity of each of its productive sectors. In addition to this, many of the technicians of the ENEL had chosen employment in a public company and within an essential public service (back then you could still choose between various job offers), rather than a job in the private industry. The totality of these factors resulted in workers focussing more on the way that work was done rather than on its result: it was not the product of work or its alien character vis-a-vis the workers that was put into question (in fact electricity was attributed with a certain social usevalue), but rather how labour was extracted within the company (the hierarchy, the command) and what impact it had in relation to the users – primarily domestic – of the utilities. So while the purpose of ENEL was that of a public economic enterprise, the labour contract of the employees was of the same kind ase in any private sector company. This put the ENEL workers, in particular the 50,000 workers in the distribution sector, in the contradictory position of sustaining a work organisation which had a clear capitalist character, but with the ‘apostelic’ halo of progress and democratic development of the nation, which was often positively referred to in trade union rhetoric. It was therefore not by chance that the first leaflet of the Political Committee ENEL was headlined with the sentence: “Also the electricians are part of the working class”, in order to stress the fact that the workers at ENEL don’t have separate interests from those expressed in the general workers’ condition in the confrontation with the bosses.

After the nationalisation of the electrical utility sector, electricity distribution in Rome was divided up between a municipal enterprise ACEA and ENEL, which created specialised departments: work centres (cable laying and construction of new lines), cabin workshops (construction and maintenance) and centres for connecting users to the grid. The latter was located in Via Baldo (northern zone) and was composed of 200 workers and 50 office staff. Workers in this department were very combative and started a series of extremely incisive strikes during the renewal of the collective contracts in 1967-68 and 1970-71. During these strikes a workers’ assembly decided to engage in strike forms that differed from those organised by the trade union, the so-called ‘hiccup strikes’, which pushed ENEL into a crisis. The workers, who used company vehicles, left the depot in the morning to connect households to the grid, but instead of going on strike according to the trade union plan (two hours on stretch or half a day) they extended the impact of the strike by breaking it up in five minute chunks, returning to the depot frequently. Practically the workers returned to the depot to strike for five minutes, in order to leave again. By repeating this two, three times a day, workers managed to paralyse the entire labour process, while incurring a minimal loss of wages. The struggle continued independently even after the proposal for an agreement for the national contract was put forward (and refused by the workers), after which ENEL and the trade unions decided, together, to subtract one hour of strike activity from workers’ wages – even if they had been on strike only for a few minutes. The struggle had a huge impact on workers in Rome and signalled the emergence of the Political Committee ENEL as a reference point for many workers. This experience marked the first distinction from the traditional left and from the unions when it came to the demands put forward in these years. It also marked a turning point in the balance of power vis-a-vis ENEL, which reacted in two ways: on one hand, the company initiated a process of restructuring which dismantled many of the local workers’ concentrations; on the other, it changed job categories and job tasks.

The agreement with the trade unions stated that the electrical utility and service sector required a multi-skilled professional type of worker who was able to perform the various tasks required by the entire labour process. In exchange for the new work organisation, the agreement proposed a paltry career advancement linked to ‘meritocracy’ (individual job evaluation, professional courses etc.). But these were not times when such concessions were met with great interest from the side of the workers, because they were indifferent, from a point of view of the content of labour, towards the knowledge of the individual labour processes, their composition and recomposition into basic and complex tasks. What interested them was to uncouple all this from the job categories – and therefore from the wage level – in a situation when, moreover, the introduction of a unitary job category in the collective contract at least in theory removed the barrier separating manual workers from office workers, although in practice institutionalised new job categories at the bottom of the wage pyramid, which resulted in pushing workers’ wages further to the bottom. Only the hypocrisy of the trade unions can make up differences in terms of ‘knowledge’ between connecting an electrical meter, joining a high-voltage cable or maintaining an electrical junction box, which would justify a ladder of three or four different levels of categories which a worker could barely climb during a working life and only after having managed to navigate the obstacle course of ‘professional training’. In reality the mass of workers learn the necessary skills themselves, they learn ‘their job’ with the help of workmates whom they often entrust their lives to, given the dangerous nature of the work. The refusal of having to be multi-skilled and flexible, and of the new job tasks which this entailed, became the terrain of confrontation for obtaining certain pay increases through the demand of automatic progression from one job category to the next. This demand for automatic progression was also opposed by the trade unions, because it undermined their capacity to negotiate contracts for the workforce.

It was very significant that the ENEL workers refused to cut off the electricity of those users who auto-reduced their electricity bills. Without an exception, those workers who had been assigned to disconnect the supply returned the service documents with the following entry: “Upon arrival the user could not be located or was not at home”. It also didn’t work for ENEL to schedule the disconnections outside of the official working hours, which would therefore be paid as overtime, as only very few took up this disgraceful task.

The agreements over the two national contracts were not enough to resolve the dispute between workers and ENEL in the area around Rome, which had been initiated by the Political Committee. The Committee managed to start another struggle over the question of ‘legality’. Disciplinary measures, in fact, constituted another aspect through which the trade union exercised the control over struggles and demands of workers: as long as these stayed within the established trade union framework, they remained protected. Otherwise, workers were abandoned and subjected to the mercy of the company’s repression, which didn’t limit itself to fines, but included suspensions and in some cases transfers and sackings. That’s why the Committee started to challenge the disciplinary measures head on, using procedures laid out in article 7 of the labour law. Workers mandated the Committee with representing them in disciplinary hearings with ENEL and the local labour tribunals. ENEL management refused to deal with the Committee, as it didn’t recognise it as a trade union organisation. The Committee reacted by filing a case against ENEL for discrimination of trade union activity. During various court sessions the judiciary decided that the trade union activities of the Committee were an established fact, referring to strike statistics from ENEL in the area of Rome which demonstrated that the strikes called for by the Committee were followed by more workers than the strikes called for by the mainstream union federations. The Committee was therefore ‘in fact a trade union organisation’ and had therefore full entitlement to represent and protect workers when it came to disciplinary measures. These court decisions were confirmed during appeal hearings and later on, in 1976, by a final decision of the high court. This was a heavy blow for ENEL and the trade union,given the fact that they had supported each other in undermining the legitimacy of the Committee, by denouncing them as an organisation of thugs, provocateurs and extremists.

Parallel to this, the Committee had also developed an intervention within the technical sector of the company, which employed around 3,000 spatially dispersed workers, out of which 900 were located in the region around Rome. This sector had to decide on technical solutions for electrical power generation and transmission, e.g. the realisation of hydroelectric, thermoelectric and nuclear power projects and establishment of a high-voltage transmission network. Therefore, mainly higher skilled workers were employed in the so-called Centre for Planning and Construction, around 80% of whom had graduated in technical and scientific courses. In these years, the National Energy Plan was launched, to which the oil crisis of 1973 had added further significance. This plan had pharaonic characteristics, as it was heavily focussed on the immediate demand side and not at all on a longer term vision, e.g. in terms of the use of fossil fuels (it was primarily based on oil and coal). The plan was a child of the developmentalist culture which was also shared by the PCI and, during this period, created convergent interests with the big industrial corporations. The crown jewel of this program was the development of nuclear energy. The final version of the Plan, which had been elaborated by the then minister Donat Cattin with the support from the PCI, envisaged the construction of twenty power plants with thousands of megawatt capacity each. Several comrades of the Political Committee worked right in ‘the heart of the beast’ – the nuclear sector of ENEL – and they initiated the push for a contestation of this plan, both in the public sphere outside the company and vis-a-vis the technicians of the Centre for Planning and Construction at ENEL, whose role as the ‘healthy carriers’ of the technical-developmentalist virus was put up for debate. Under the pretentious slogan of “we have to give more energy to the country” these technicians were turned into instruments for a massive operation, at the heart of which was ENEL: the transfer of resources and capital from the state coffers towards the private capitalists through the channels of electrical supply.

The struggle around the role of technicians was certainly not a ‘vanguard struggle’ – as it was called back then. Nevertheless, because we did not confine it to the company level, but managed to relate it to the struggles that emerged in the territory, the struggle contributed significantly to the eruption of the movement against nuclear power. It was a major problem for ENEL to interpret and contain the protagonist, these technicians who put up for debate both the decisions concerning energy policies and the organisation of work inside the company. There was a very visible contrast between their struggle, and the trade union organisations and the PCI, which maintained a party cell within the company that was particularly active amongst clerical staff. Also the forms of struggle that the Committee pushed forward did not conform to what you would expect from ‘white collar’ workers – internal and external protest marches, hard pickets, like the one that blocked the national headquarter of ENEL in Piazza Verdi during the strike for the collective contract in 1973, to which the employees of the Centre for Planning participated with conviction and contentment. On that day, Angelini presented himself at the picketed entrance and demanded, in an haughty manner, to be given access given that he was the president of ENEL, but he received only one collective response: “And who gives a fuck!”.

This is how, in the eyes of the workers ‘those from the Political Committee’ became the punishers of the company, while the latter displayed to an increasing degree a ‘bosses’ attitude’, and there wasn’t a struggle of workers or employees that wouldn’t find a resonance in the various workplaces within ENEL, of which there were around 20 in the Rome region, employing a total of 4,000 workers. Obviously the struggles of the blue collar workers were more incisive, because they threatened customer supply. But the nuisance that the struggle of the office staff caused ENEL was enormous – for example, when the company decided to close down the nursery that female office workers were using at the headquarters and the Centre for Planning. In response, the Committee organised an occupation of the rooms of the council administration building together with these workers. This forced the councillors (who represented the entirety of political parties) to engage in closed negotiations for as long as it took, until the late evening, to revoke the closure and reinstate nursery workers who would otherwise have lost their jobs.

However, even if the initiatives of the Committee in the streets of Rome enraged the central power of ENEL ‘close to home’, its actual presence within the total manual workforce was marginal, given the vast numbers of electricians – around 90,000 – and their dispersed character within the national region. The Committee managed to find links with other workers’ structures in ENEL that intervened in Turin and Milan, and that politically referred to Lotta Comunista. For a few years (and not without difficulty, given political differences) this gave life to some coordinated struggles; but these were too few to impose themselves and shape the national contract demands for ENEL workers […]

Auto-reductions

After it was created, ENEL was given the enormous task of modernising the entire electricity network and connecting many areas to the grid that hadn’t been before. In order to do this, ENEL needed fresh capital through taking up further credits, which increased the debt burden of ENEL vis-a-vis the national electrical corporation. In consequence, the attitude of the political left, which was responsible in parliament for overlooking the functionality of the only instance of nationalisation in the Italian Republic, was that of shifting the weight of the debt onto the shoulders of workers and consumers. They did this by limiting wage demands and regulations to protect the existing organisation of work, and by increasing the price for electricity, without questioning the classist character of the tariff system which penalised domestic consumption. Inn schematic terms, the general situation was that the industrial sector contributed 32% of ENEL’s income, while consuming 65% of the total electricity produced. The domestic and commercial sector, on the other hand, consumed 35% and paid 68% of the bills.

The first bigger struggle around electricity bills emerged in 1972 in the northern periphery of the city, in the neighbourhood of Montecucco, along Via Portuense, which leads from Rome to Fiumicino. Rather than being a real neighbourhood, Montecucco is more of a typical settlement of popular housing built in the post war era, divided into identical and ugly blocks which were sufficient to make the ignorant passerby understand that it was proletarians who lived here: a dormitory town without shops or buses.

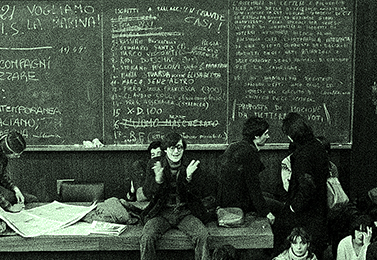

This area is supplied by ENEL, which had recently adopted a ‘precalculated’ payment scheme, where the electricity bill is estimated using figures of previous consumption. This was primarily done in order to reduce the number of workers engaged in meter reading. As a result,exaggerated electricity bills started to appear in Montecucco and the residents decided spontaneously to stop paying and to protest in front of the ENEL company office of the Lazio district. The protest was suggested by the Political Committee ENEL, which had been contacted immediately by comrades who were active in the area. The demonstration was successful and the director Sassano, who saw his office occupied by around 50 protestors (the rest remained outside), took on the job of dividing the bills into smaller installments, and verifying the actual consumption that had to be paid for. After this initiative, a long discussion took place at the office of the Autonomous Workers Committee in Via dei Volsci and the question circulated in the minds of the participating comrades: why didn’t we come up with this idea ourselves?

The lessons the proletarians of Montecucco taught us made us realise that without a concrete and consequent form of practice, our ‘badass’ reasoning about income and illegality was merely mental gymnastics. Furthermore, this working class behaviour meant ‘illegality in practice’ and refusing ‘de facto’ the imposition of capitalist command and established rules, in order to reappropriate – at least partly – those shares of income that would otherwise be inaccessible. The reason why we called the following process – from electricity to telephone bills to transport prices to consumption goods – ‘autoreduction’ was to underline both the self-organisation of struggle, and the will to leave open the dialectic relation between power and counterpower on the one hand, and on the other the perception of what is fair and equal when it comes to the price of services and goods.

We decided, then, that the example of Motecucco should not stay isolated, but be spread and generalised in the wider territory. The comrades form the ENEL took it upon themselves to analyse the tariff structure and process of invoicing that the company was using. It became apparent that domestic consumers paid five times more for the electricity than the average industrial client. They also found out that the prepayment method based on the company’s assessment (which was not applied in the case of industrial consumers) was forcing 18 million domestic users to pay in advance for what they hadn’t actually consumed yet. This resulted in one of the biggest deceits of nationalisation, given that during the transfer from private to public control, the tariff system in place during fascism was left untouched. This tariff system meant that the bosses had cheap access to a prime resource, while the proletarians had to pay dearly.

It was obvious that the discourse that started would revolve around the question of what a ‘fair’ price for energy is – but what party or institution was able to actually question the unjust tariff system? It was therefore decided that our reference price for our campaign for autoreduction was that which, according to our estimates, the average industrial client paid. Soo 8 lire/Kwh instead of 45 lire/Kwh that domestic users were paying at that moment.

The actual autoreduction therefore wasn’t born in Montecucco, as is often said, but rather emerged out of elaborations we undertook in relation to the spontaneous behaviour of the proletarians in the neighbourhood. Spontaneous non-payment could neither have gone beyond arefusal to pay absurd bills (which, furthermore, were softened after the reassurances by Sassano to reexamine the calculation); nor could they have established a ‘fair’ price for electricity, in a way that ENEL would not have been able to accuse them of defaulting on payments. Based on our analysis, we could show that part of the bills had already been paid. Autoreduction can therefore represent one of the best examples for the schema ‘practice – theory – practice’, in the sense that the initial refusal to pay for the bills, once further developed on a theoretical level, allowed the initiation of a mass struggle of large dimensions.

The major effort in terms of organisation was put into practice byneighbourhood collectives: leafleting, public announcements in the streets, mobile assemblies of tenants to explain the motives of the struggle, gathering of bills, multiplying the practice of paying only 8 lire and writing on the bank transfer reference that “we pay 8 lire like the bosses do”. To retell all this is easy, but to put it into practice is a different story.

There were hesitations and confusion amongst people, because they were doing something outside the rules. But even among those who didn’t taket part actively maintained that the struggle was justified – in particular the women, who often knew more about the family budget than the men. The campaign grew slowly but steadily during 1973, then accelerated at dizzying speed in the following years, when living costs increased significantly. This is when ENEL, who had initially limited themselves to observing the situation, started various repressive actions: from letters to consumers threatening to cut the electricity supply, to actual attempts to disconnect households from the grid. These turned out to be unsuccessful, either because the workers refused to disconnect, or because of pickets organised by housing blocks where autoreduction happened.

ENEL was therefore forced to try the legal route and file cases against people for defaulting, which included claims for compensation payments for damage. These legal measures also didn’t have the anticipated results, given that we could give evidence of the unfairness of the prepayment calculation in court, and furthermore prove that people were not defaulting, but rather paying a reduced amount.

In the same year, with the support of the comrades of the ‘struggle group’ that intervened amongst workers of the communication company SIP, we decided to start a campaign to autoreduce telephone bills, calling people to only pay the basic line fees.

SIP, who acted as a contractor for the state, had managed to obtain from the government a price increase of 10 lire per call and a change to previous conditions, which had included 145 free calls in the basic line fee – meaning that the final phone bill doubled. This was a mean attack on those with the lowest income, who were already reeling under the pressure of double digit inflation, and who were not receiving compensation payments sincethey were not employed under existing collective bargaining agreements.Furthermore, it was a hateful measure of classist nature, similar to the increase inelectricity bills, as it insinuated that for working class households telephones or light were a luxury and not part of a normal evolution of basic needs in a developed capitalist society.

The struggle developed with unexpected speed despite the fact that, unlike ENEL, SIP put in place repressive measures immediately, by sending letters threatening disconnection of phone lines. This necessitated a wider level of mobilisation: you couldn’t gather local tenants to prevent disconnection, given that they were implemented centrally and not house by house, aswith the electricity supply. At least theoretically, the payment of the basic line fee should have guaranteed that the service was not disconnected. But it quickly became clear that this was not going to be a legal battle, but rather dependent on the real balance of forces between those who struggle for autoreduction and the company. It was therefore necessary to engage in permanent protests in front of the local SIP office and to involve all other institutions that were responsible for this indiscriminate price increase, which meant an additional workload for groups active in the area. On the other hand there was no lack of sharp responses to disconnections enacted by SIP, for example in the form of an arson attack on the local telephone switchboard – which also affected manyusers who were not part of the struggle.

In a short time, the numbers of cases of autoreduction of electricity and phone bills in Rome grew to several ten thousands and once this struggle extended to the national level we saw hundred of thousands of families practising this form of ‘reappropriation of wealth’, provoking many disagreements within the trade unions and the PCI. In the north of the country, most of all in Torino, significant numbers of union delegates (in some cases entire factory councils) organised the autoreduction of ENEL bills, while in other cities it were the linked autonomous organisations that expanded the struggle. Often, autoreduction targeted additional aspects like transport, basic food, rent; especially in towns like Mestre, Rho, Bergamo and Genova, and wherever structures of organised workers’ autonomy were present.

In the working class neighbourhoods of Quarto Oggiaro in Milano; in the industrial zone of Marghera or in Rome; people organised the first actions of ‘proletarian shopping’ in grocery supermarkets. In some cases they left a lump sum for the taken goods, in other cases not. “They paid with a handful of leaflets”, was the least harsh comment that appeared in the media, while later on the media treated these actions as some sort of collective theft, also because in a couple of cases the press denounced the fact that in the general turmoil money was taken from checkout cashiers. But even without these aggravated cases, it was clear thatproletarian shopping was treated as illegal, and all the political parties emphasised this fact. The ‘expropriators’ had strong arguments on their side, given that living costs increased by 20% in a single year from 1973 to 1974, and that it was the prices of basic goods and services that were literally ‘targeted’ with hikes. It became clear that the questions these acts of autoreduction brought to the fore concerned the political sphere, because, while all parties paid lip service to the aim of cooling down inflation and capping bills and other virtuous measures, the fact of the mechanism of crisis within the relation of production (which was a general and international crisis) presented itself like an uncontrollable demon, meaning, you had to take sides: you were either on the side of the workers and proletarians, or with the companies and their profit. In short: either with capital or labour. And all the political forces and trade unions chose the side of capital. It goes without saying the ‘politics of sacrifice’ were not put up for vote in factories and working class neighbourhoods, but imposed in the ‘general interest’ of the nation. No one on the left can be absolved from not trying to find a different way out of the crisis of the ‘damned 1970s’ – the consequences of which the left still pays dearly for. However they denounce the actions of these years on the plane of the reappropriation of wealth, they also bore fruit on a formal level, given that in 1975 a price cap was introduced for domestic electricity users, followed by the abolition of particularly unfair line fees for telephone services, and the foundations for a fair rent law – the outcome of the long wave of housing struggles.