Beyond White City – Some Snap-Shots on West London Workers’ History

In order to get our heads around Greenford, Southall, Park Royal area today, seeing how this area developed over the last century can help. Below you can find some first random excavations. We take it as a background for future more specific articles, local walks and interviews with local working class militants, who have been around and active much longer than we have. We also plan to turn some of this material into articles for our local workers’ paper: many workers from Poland know little about the struggles of Black workers in the 1960s and 70s and colleagues in general are probably not aware about the mass militancy of organised workers which shook this area half a century ago. Most of the historical material ad quotes we found in a splendid new book: “All in a day’s work – Working Lives and Trade Unions in West London 1945 – 1995”, edited by Dave Welsh, which is a good read.

*** A Short Summary

Being stuck to the far fringe of big London town the development of the western part were determined by changes in infrastructure, industries and working class migration. To summarise the main shifts:

* From the mid-1850s onwards the existence of the canal network facilitated early industrialisation in Greenford area, e.g. glass manufacturers, chemical plants and tea factories. The construction works on the western railways, in particular around the rail depot in Southall, and the Western Avenue (A40) brought in hundreds of labour migrants from Wales during the 1920s and 1930s. Southall, Perivale and other parts of Ealing area became a strong-hold of the Labour Party during this time.

* The post-war period saw a rapid expansion of the engineering industry, in particular in Park Royal, attracting many workers from Ireland, Caribbean and from the 1960s onwards from South Asia. Widespread wage struggles of the 1950s were followed by strikes and street protests against the racist factory and migration regime and for equal pay by the new generation of migrant workers, who were not represented by the institutions of the old labour movement. During this period the Communist Party had a major influence on the shop-floor of the bigger factories.

* By the end of the 1970s engineering went into decline, west London lost 22,000 engineering jobs in 1979 – 81, representing a 17% reduction in just two years. The re-structuring brought forth struggles such as at the Lucas plant where engineers and skilled workers raised the issue of workers’ self-management and ‘socially useful production’. These disputes remained isolated incidents and were not able to put a halt on mass redundancies.

* During the 1980s job cuts in engineering were partly compensated by the massive extension of Heathrow airport and logistics and warehouse districts (in total 80,000 ‘airport-attached’ workers), which initially employed mainly South Asian workers and from the 2000s onwards increasingly new migrant workers from Eastern Europe. Park Royal has changed from an industrial area of aerospace and automobile engineering to an archipelago of food processing plants, warehouses, small manufacturing units and offices – with a Cross Rail station to open in 2018.

Below you can find more concrete excursions into the past – to be continued.

*** “A fertile place of corn” and early anger against enclosures – Greenford before the 20th century

The UK radical left is fascinated with the period when proletarians were not yet workers, when everything seemed more romantic and riotous, and, let’s be honest, comfortably long time ago. In order to satisfy the this type of fascination, we start our history tour with some antics.

Twentiseven people at Greenford are mentioned in Domesday Book of whom one was a Frenchman, and by the early 13th century there were 47 tenants on the Westminster manor. Wheat and barley were certainly being grown in the 13th century, as well as rye in the 14th, and hay formed another crop. Sheep, cows and bullocks, and pigs were among the stock exchanged between Greenford and other Westminster manors near by in the 14th century. After the Reformation, when the manor had passed to the bishopric of London, Greenford was described as a ‘fertile place of corn’.

Enclosures appear early in Greenford. An inclosure of land was conveyed in 1431, and by 1601 the glebe had already been inclosed. In 1613 there were two complaints that crowds had torn down some fences. Land seems to have continued to be inclosed, however, and the manor court often ordered people to remove encroachments and fences. By 1775 well over half the parish had been inclosed.

Until the mid-19th century it is probable that the population of Greenford was almost exclusively employed in agriculture. In 1841 there were 76 labourers living in Greenford who were employed by the Great Western Railway, but by 1851 they had left. During the 1850’s and 1860’s the chemical works provided employment. By the beginning of the 20th century there seem to have been 7 farms. By 1938 the sole remaining one was Oldfield farm, which cultivated over 150 acres, but by 1959 this too had disappeared.

The first factory in the parish was built at Greenford Green in 1856. It was erected by the chemist, William Henry Perkin, who had just discovered the first aniline dye, Tyrian purple or mauve. By the end of 1857 the works were in use and were the foundation of the coal-tar industry. In the 20th century industrial development started with the establishment of W. A. Bailey’s glass-works in 1900. The selection of Greenford is said to have been due to ease of communications by canal and the almost certain development of road and rail communications in the near future. [1]

*** From Greenfields to Industrial Estates – Development between the Wars

The first major boost in industrialisation of London’s west took place in the 1920s. In 1914 Park Royal had been completely rural, by 1929 around 140 factories were located there, employing 14,000 workers. The Guinness Brewery, built in 1935, was the biggest single development on Park Royal and needed the close proximity of rail, arterial roads and canal facilities. In Greenford J. Lyons & Co. Ltd. had established their factory by 1926, when it employed 3,000 workers. The factory was at first designed for tea-blending and later also produced tinned coffee and confectionery. The British Bath Company, one of the group of Allied Ironfounders Ltd., was established in 1928, manufacturing sinks and bath tubs. The Glaxo works were established in 1935. They produced infant foods and pharmaceutical products, including penicillin. Acton saw the emergence of major industrial laundries. Also the first US-American companies opened plants during the 1930s, e.g. Hoover opened their factory in 1932 in Perivale, employing 800 workers.

The jobs attracted new workers, many of them settled over from the London East End, some of them complaining about to much fresh air and the subburban boredom. In the 1930s in Ealing a skilled worker could buy a house with the equivalent of two years wages. These workers became the backbone of the rapidly growing Labour Party, in particular in Greenford and Northolt, which established various social clubs, reading groups and dance festivities in the area. During the 1926 general strike around 50,000 people gathered on Ealing Common, to listen to party speakers. Not only the party tried to organise workers’ lives, they competed with the American style corporate paternalism of companies like Hoover, which offered similar activities and corporate housing schemes. Between 1921 and 1931 the Middlesex population grew by 30 per cent, which was the biggest growth of all England’s counties. Many of the new workers came from Wales.

The Golden Years didn’t last long and by the end of the 1920s unemployment became a major problem. In Ealing over 2,000 unemployed gathered to demand jobs. The Labour Party, by then running the council in Southall, tried to create jobs schemes for the extensions of the Piccadilly tube-line and the A40 motorway. Unemployment created tension within the working class, e.g. anti-Welsh slogans and graffiti in Southall (which were changed to ‘Blacks/Irish out’ in the 1950s and ‘Pakis out’ in the 1970s). The Labour Party, which mainly represented the more established workers, could do little to change the structural causes for unemployment, so instead tried to manage it in favour of their voters and thereby deepened certain divisions: it is interesting to note that Acton Labour Councillors supported Acton Council’s plan to dismiss married women public employees in 1934 (if their husbands were on good wages). Some members of the Labour Party thought that the right-wing turn of the party did not go far enough and created their own ‘labour party’: Ealing Labour Party member Oswald Mosley had been the Labour Club president in Hanwell in 1926 and later on became the founder of British fascism.

The sell-out of the Labour Party after the general strike in 1926 had also increased the membership of the Communist Party. The Young Communist League was active in Southall and organised various antifascist / popular front actions during the 1930s against the fascists – 40 years before the big anti-National front riots in Southall in the 1970s. Unsurprisingly the antifascist actions of the labour left were less direct than rock throwing, an older activist “recalls taking action against the Blackshirts in Southall. The idea was to surround them completely with sellers of left-wing newspapers so that they could not escape.”

[2]

*** ‘This west London militancy’ – Wage struggles in the engineering industry in the 1950s and 1960s

“Big industrial site, Park Royal. A firm called Beatonson’s and they made components for cars – for Fords mainly.. I had learnt all manner of different things, you know, on drilling machines and press tools and capstans, what they call semi-skilled work… (…) And I’d learnt enough about operations in the Beatonson’s firm… we had a full-time nurse there. Because, in those days hundreds of different kinds of machines were all driven by overhead shafting, from master motor (and) those belts used to break from time and time and slap into peoples’ faces.”

Bill Richardson

In the 1950s West London had the biggest concentration of manufacturing industry in London and one of the biggest in Britain: double-decker buses were built at AEC chassis works in Southall and in Park Royal, Rolls Royce parts were manufactured at Mulliner’s, alternators and dynamos at CAV in Acton. In 1958 there were twenty airframe companies and six aero-engine firms based in and around Park Royal. The aircraft industry was dominated by Lucas Aerospace. In 1967 Lucas owned two Rotex factories at Park Royal an Willesden and one in Hemel Hempstead. The typical pattern in aircraft engineering was found at Rotax, with a research centre of 300 staff, an experimental production facility making prototypes with 400 people, a tool room of 200 people and further 600 skilled engineers who had done seven-year apprenticeships. West London also contained many small factories. Flexal Springs and F.Edwards Ltd in Acton doing precision turning, grinding and capstan lathe work, Landis and Gyr Ltd producing electricity metres… Woolf rubber factory, foil making in Ruislip. The post-war boom attracted new workers, many of them brought with them experiences of struggle from their regions of origins.

“I first came to London in the 1950s and found work in the engineering industry. I was soon involved in the Trade Union movement both at factory and union branch level. Coming from Dublin my parents had made me aware of the part played by James Connolly and James Larkin in the struggle of Irish workers, a lesson not to be forgotten, it followed that I would be involved in London.”

Billy Taylor

“I was born in the west of Ireland in 1939 and in 1957 I came to London to work and live with my sister in Kilburn. Later I was given a job at McVitie&Price biscuit factory towards Harlsden. There was machines that wrapped the biscuits, (…) there was about ten of us working on the conveyor belt packing the biscuits into these machines (…)”

Rose Madden

From the mid-fifties, full employment gave workers a new confidence. Wages were good in west and north-west Middlesex so that if employers didn’t pay well, workers could leave and find better paid work elsewhere.

“I left my first job at Marks&Spencer to join Heinz at the age of 16 because they paid more money. I was an operator in charge of a line of people who filled bottles of salad cream coming along the conveyor belt. (…) As the union was so strong, we had good working conditions. We also had a good social club, where drinks were cheap. They laid on lots of events such as dances; they had a good sports and social section, they did just about everything. They were an American company that looked after their workers.”

Myra Scales

In many industries, many workers were paid by result (piecework), a system which offered shop stewards and shop-floor workers the chance to bargain under the threat of stoppages. There was a ten-year national ‘strike wave’ in Britain from 1952 to 1962. Many strikes were unofficial, local, short-lived and usually triggered by dissatisfaction over pay rates. Shop stewards were increasingly blamed for strikes. The union hierarchy and the Labour Party dealt with this militancy by first expelling ‘communists’ from union positions in the 1950s – based on the Transport and General Workers’ Union (T&G) ban voted for in 1949 – and by promoting more centralised collective bargaining in the 1960s. The Donovan Royal Commission, set up by the Labour government in 1965, reported in 1968. It argued that collective bargaining should be encouraged and that no employee should be prevented from joining a trade union. it said that the ‘informal’ system of local bargaining should be regulated as this would reduce unofficial or ‘lightning’ strikes.

Although union membership increased during the 1950s, the idea that people had a ‘job for life’ in these years is far-fetched. Short economic recessions occurred in the fifties and sixties causing unemployment. Thousands of jobs were lost in the coal and railway industries and the number of strikes over redundancy suggests that jobs were far from secure. In 1945 for example, Napier’s threatened redundancies and a demonstration of 9,000 people outside Acton Town Hall protested. Nationally, redundancies ran at a rate of 200,000 a year in the period 1956 – 58 and 5% of working days were lost in 1960 – 65 in strikes over redundancies before the Redundancy Pay Act of 1965 came into play.

[3]

“My introduction brief is to write something about working at Kodak. The Kodak site at Harrow produced photographic film and paper and I worked there from 1966 to 1991 for seventeen years as a machine operator on shift work including weekends. (…) The main production was spread across the site, each department in its own building. Workers rarely changed departments which created a form of department tribalism. You required permission to leave the building. I moved to one of the largest departments – film finishing. here, working relationships depended on inter-action between workers and shift supervisor. For three years I ran a film-spooling machine, converting large rolls of film to the normal camera cassette product. I worked alone in a darkroom doing 12-hour shifts. (…) Moved to the film packaging department. A large open factory filled with machines. The packaging machines range from 8 man to one man machines. The machines can pack 500 films a minute and a faulty cartridge can damage 300 others in seconds. A shift’s production is worth millions of pounds, theft on both small and large scale is a problem. (…) Disputes between operators and supervisors are always possible. With good management it’s difficult to control, with poor management it becomes a serious problem. (…) Kodak was a large employer and is the sum of its parts. The wages were good and the social provision in terms of sporting facilities and social clubs for both past and present staff was first class. (…) I left in 1991 and ten years later Kodak closed its gates.”

Phil McManus

*** The ‘other’ workers’ movement – Struggles of (migrant and female) mass workers in the 1960s and 1970s

Industries continued to grow during the 1960s, for example in Park Royal industrial employment increased from 14,000 in 1930 to around 45,000 in the late 1960s, working in 500 firms. While the official institutions of the labour movement mainly focused on the higher skilled workers within the engineering industry, unrest fermented in the rapidly developing mass industries characterised by ‘unskilled work’, where many migrant and female workers were employed.In west London some of the bigger company names employing largely unskilled workers were Wall’s, Napier’s, Nestle’s, Heinz, Hoover, Lyons, Optrex, ENV, EMI, Gillette, Kodak, Coty and Guinness. A company like United Biscuits required a local workforce with women in low-paid packaging jobs and men as semi-skilled machine-minders. Some 80% of workers at its Harlesden factory were Black. Without these Commonwealth immigrants, such companies would not have been able to make their (food) products. Similar to the migration from Ireland before, the new migrant workers often brought with them class struggle and political experience. We quote from short biographies:

“Born in the Punjab in 1921, Vishnu Sharma was active in the peasant movement and later in trade unions, becoming Assistant General Secretary of the Punjab Provincial TUC at a time of the British Raj. Because of his militancy, he was arrested six times and imprisoned for a total of three and a half years. He was forced to stay in his village for 21 months and visit the police at 11am every Sunday. Sharma joined the Communist Party of India in 1937. He left for Britain in 1957, speaking no English and with just three pounds in his pocket. He immediately joined the British Communist Party. He worked in a rubber factory in Southall, taught himself English and immersed himself in trades unionism; Sharma became a member of the British Communist Party’s Executive Committee from 1971. Long active in the Indian Workers Association, he was elected President of the Southall Indian Workers Association (IWA) established on 3rd March 1957, by some of the younger more radical elements of the Punjabi community in 1957.”

[4]

In the years immediately after the war, new arrivals came from all over Europe. These included a small number of German prisoners of war, a larger number of refugees from the ‘Communist regimes’ in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union (130,000 Poles arrived during the first few years after the war, and 14,000 Hungarians after the failure of the 1956 uprising in Hungary). During the first decades after World War II the British state developed a migration regime from the former colonies aiming at an adjusted supply of cheap labour for industrial re-construction.

According to the Home Office estimate net migration from the Commonwealth from January 1955 to June 1962 was about 472,000. By 1970 around 1.5 million migrant workers resided in the UK out of who the Irish remained the largest immigrant community. With the economic downturn in the late 1960s/early 1970s and increase in unemployment the state started to use and promote ‘anti-immigrant sentiments’ in order to build the ground for more restrictive migration laws. The Labour Party passed the ‘Kenyan Asian Act’ in 1968, in order to curb migration of Indians expelled from Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. The legal changes often targeted both migrant and local workers, e.g. the Immigration and Industrial Relations Act from 1971. By 1973 only Commonwealth citizens from Australia were allowed to enter the UK, all Black folks from the former colonies had to provide specific job contracts. Not only in west London new migration and racism amongst local workers caused tension:

“I was called to a mass meeting in 1961 and the reason was the company was about to employ a black labourer. I got there, I listened to this and to my shame I hadn’t realised that there wasn’t a single black person working in the whole of the company of about 1,000 people. I listened to what I found to be bizzare and bogus arguments. People were saying “he’s taking the job of my mate, my son”…Bert, a communist, put his hand up and spoke for some while about the need for an understanding we ought to have about working people and the way working people encompasses black and white people… the whole mood of the meeting changed and a decision was taken that he should be welcomed.”

Gary Fabian

In most cases the new migrants had to fight racism themselves, as either no ‘saviour communist’ was around or members of the old labour movement were pretty anti-migrant, too. For example, in 1962, at the height of election wins of the racist British National Party (BNP), Labour MP George Pargiter called for a ban on migration to Southall, basically repeating the demands by the BNP front-organisation ’Southall Residents Association’. The BNP had won 13.5% in Glebe and 27.5% in Hambrough where the Labour Party lost a normally safe seat to the Conservative Party after a swing from Labour to BNP. Consequently five Labour councillors wanted to back a 15 years residency qualification for access to social housing, in order to exclude migrants. They later left Labour and joined the BNP.

“I came to England (in 1966) for a better life and for a new experience. After Manchester, I moved to Luton and worked on the line at Vauxhall’s, and then I went and worked as a press operator at John Dickenson’s stationery firm in Watford. I came to London and started as a machine operator with Perivale Gutermann. It [was] a factory making silk thread, and the main workforce Asian from India and Pakistan. Before 1969 there wasn’t any trade union organisation at Perivale Gutermann and people say life then wasn’t very good. They used to work 12 hours a day, 7 days a week for, say £30 a week. We have been able to establish a branch of the T&G and decent, basic rates of pay for our fellow workers… In 1973 there was a group bonus imposed on us. This was the main stumbling block [and] the management presented a list of 30 active members and said “accept the group bonus or we will make them redundant”. We banned overtime and, as a result, all of us trade union members were locked out on 4th of December 1973.”

Akbar Khan

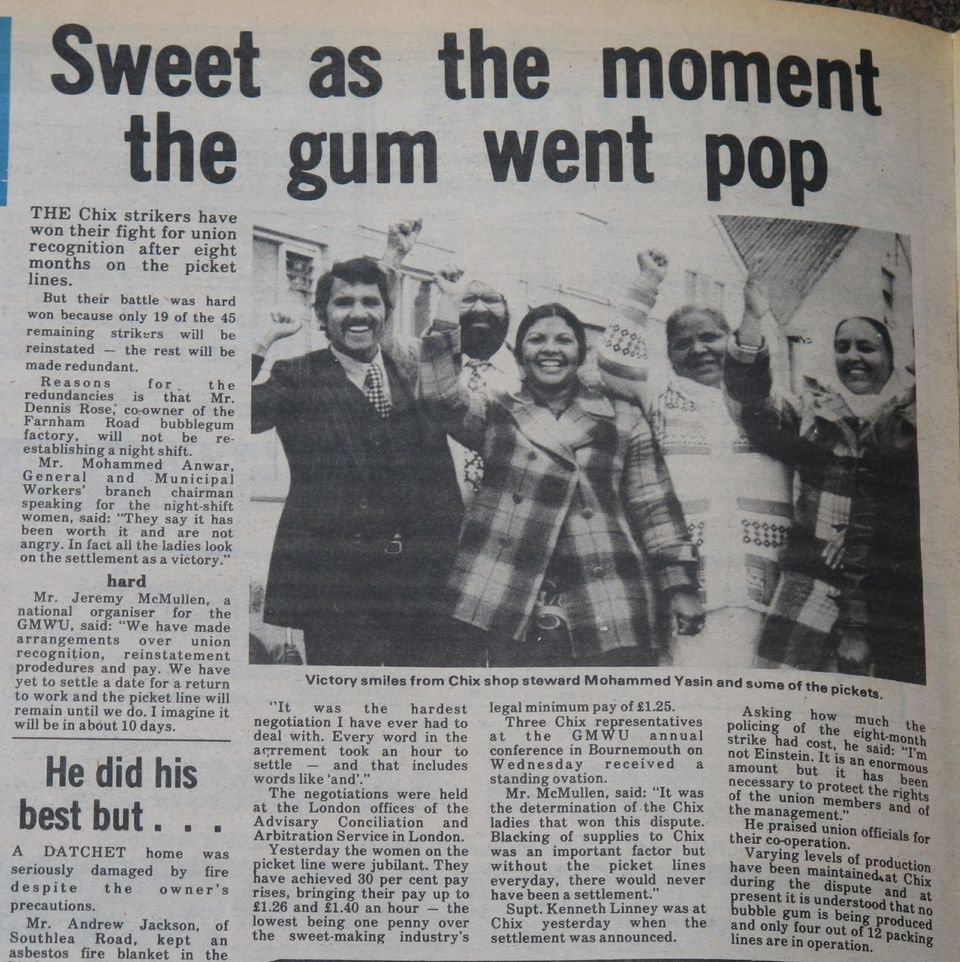

From the Notting Hill Riots in 1958 to the Southall Riots in 1979, Black proletarians had to organise self-defence against violent racism. In Southall, three years after the racist murder of Gurdip Singh Chaggar, the National Front tried to hold a meeting in town hall in 1979. Thousands came to stop the fascists, they were attacked by the police, the cops killed one demonstrator. When writing about the Southall Riots in 1979 people often forget to mention that on that day around 20,000 local workers went on unofficial strike to support the protest. They knew that the battle has to be fought both on the streets and at work: at the AEC British Leyland plant in Southall, unions and management had agreed on quotas, limiting job prospects of Asian workers in the 1960s, basically imposing a ‘colour bar’. The NF managed to mobilise 200 AEC workers to a ‘Send them back’-march in 1969. From the 1960s onwards a series of wildcat strikes led by mainly Afro-Caribbean and Asian workers shook factories in the UK, confronting not only management, but in most cases also trade union leadership, and leading in some cases to open conflict with white colleagues. Apart from Greater Manchester (Redscar Mill strike in Preston, 1965) and the Midlands (Tipton Coneygre Foundry, Midland Motor Cylinder Co., Newby Foundry West Bromwich in 1968 and Leicester Imperial Typewriter strike in 1974), west London was a hotspot of migrant/female/unskilled workers’ discontent: Rockware Glass, Woolfs Rubber (Southall) in 1965 , Gutterman (Perivale), Chibnalls Bakery, Futters (Harlesden), Quaker Oats (Southall) and Chix (Slough) in 1979. These struggles merit greater attention, but due to lack of (online) available material and space, here just a few examples. We summarised stuff also about struggles outside of west London, given that there was more material available, e.g. on the Imperial Typewriter strike in Leicester, which can explain in more detail some general tendencies during this period:

* The Woolfs Rubber strike in Southall, 1965

In the 1930s Woolf had employed workers from Wales After the war management started to recruit mainly migrants from Punjab. The factory conditions were particularly bad: low wages, old machinery, bad health and safety conditions, long shifts of up to 70 hours per week. Besides, management offered promotion mainly to white workers. The divide-and-rule was also applied during strike, when the bosses started recruitment of Pakistani workers from Bradford, trying to stir tension with the local Punjabi Sikhs – which did not work out. The T&G had been formally recognised in January 1964, but repression continued after recognition. This led to several unofficial walk-outs during early 1965, during which workers demanded higher wages and less overtime. The union officials tried to get workers back to work, promising future negotiations. The last strike broke out after the victimisation of a shop-steward, it lasted six weeks. Initially the T&G gave formal support, but refused to hand out strike pay, claiming that workers hadn’t paid their subs. A return to work was negotiated in January by the Ministry of Labour, together with the Joint Industrial Council for the Rubber Industry. The agreement promised reinstatement of the strikers, but there contained no guarantees about what job strikers should return to. 100 workers did not return. The best jobs were kept by scabs. Woolfs closed in 1967.

[5]

* The Mansfield Hosiery Mills strike, 1972

In October 1972, Indian workers at Mansfield Hosiery Mills, Loughborough, went on strike to press a claim for higher wages and for the right of promotion to jobs reserved for white workers. The National Union of Hosiery and Knitwear Workers at first refused to back the strike and when it was eventually forced to do so following an occupation of its offices by the Indian strikers, it refused to call out fellow workers who, of course, were not supporting a strike which had as one of its aim the elimination of a privilege gained by a racist practice. The report of the Commission for Industrial relations, 1974 warned that if action was not taken to eliminate such practices, there was a real danger that those excluded from promotion to the ranks of the skilled and the higher paid by their own union might take the logical step of forming their own. The implication was clearly stated, and then underlined by further, similar disputes at E.E. Jaffe and Malmic Lace in Nottingham, Standard Telephone and Cables in Southgate.

[6]

* The Imperial Typewriter Strike in Leicester, 1974

The firm was a subsidiary of the multinational Litton Industries. In the factory the prevailing rate of pay for men was £14 (around 30 to 40%) below the national average, while the women workers’ pay was £6 below. Having installed new machinery and generally updated its production operations in Leicester and Hull, the number of workers employed by IT doubled, from 1,900 in 1968 to 3,800 in 1972. Interestingly, until 1968, Imperial’s employees were all white. Thereafter, it was noticeable that recruitment was centred largely on Asian workers. Of the 1,600 employed at the Leicester factory, approximately 1,100 were Asians. Productivity of these migrant workers brought about a turnover which more than trebled between 1968 and 1972 from £3.3 million to £10.8 million. Since 1972, although productivity ‘increased enormously’ bonus levels were re-negotiated downwards. To further reduce labour costs, more women were employed. When the Asian workers turned to their union for help, they soon realised the true nature of the union’s role. They were reminded by their union negotiator of the need to keep the company as a going concern. He wrote to the strikers: ‘You are ill-led and have done nothing but harm to the company, the union and yourselves.‘

The rumblings came to a head on May Day (the day of international working class solidarity) when workers from four firms in Leicester took action. The walkout involved 300 workers at the British United Shoe Machinery; 300 at the Bentley Group, 200 at the General Electric Company factory in Whetstone, and 39 Asian workers who left section 61 of Imperial’s factory. The substantial numbers engaged in the walkout action from the first three firms soon walked back to work. In spite of this psychological disadvantage the majority of those workers who walked out from Imperial’s factory stayed out, and managed to bring out a further 500 workers with them. This withdrawal of labour had the desired effect: within a few days production fell to 50 per cent of normal and fell much further as the strike entered its fifth week. At the beginning of the strike, the main issues were about bonus rates and producing progressively, first 16, 18, 20 then 22 machines every day for the same wages. But, as the strike evolved, a host of related grievances became integral. Moreover, the strike was about racism reflected in the election of shop stewards and the preferential treatment for white workers who could clock in their mates, while Asians were not allowed to do so. Between 50 to 200 workers manned the picket line continuously. The women workers played a central role. They engaged in a ‘fearful howling and hollering’, whenever a scab or representative of management appeared. Tremendous noise (echoing down the street) was an outstanding characteristic and an effective factor in the picketing. The myth of the Asian woman’s passivity was debunked as her presence was not only felt, but heard. As the struggle wore on, Asian youth increasingly became a part of the strike scene. Nine days after the strike started, the company sacked 75 of the original strikers. In protest against this action, the workers refused their cards. Instead, they sent them back.

The trade union’s position in this strike was revealed by the T&G negotiator, George Bromley, a JP, ‘stalwart of the Leicester Labour Party’, and one of the ‘lieutenants of capital’. “The workers have not followed the proper disputes procedure. They have no legitimate grievances and it’s difficult to know what they want. I think there are racial tensions, but they are not between the whites and coloureds. The tensions are between those Asians from the sub-continent and those from Africa. This is not an isolated incident, these things will continue for many years to come. But in a civilised society, the majority view will prevail. Some people must learn how things are done…”. In referring to the tensions between African and Indian Asians, Bromley totally ignored the racial tensions that already existed between the Whites and Blacks as a direct result of a large National Front presence in Leicester. Indeed the NF had polled 9000 votes in the previous elections. The NF also tried to threaten strikers in front of the factory.

Although the company was ‘willing to talk’, the T&G negotiator, feeling that his authority had been undermined, hindered the process. He said he was not ready to talk to any but the strikers’ leaders. In his diligence to undermine the strikers, Bromley conveniently discovered a T&G rule to the effect that workers could not be elected as shop stewards until they had been at the factory for two years. Four factories with large Asian memberships aided the strikers with donations to the strike fund and pledged a 24-hour stoppage at their factories ‘if and when needed’. Significantly, at that point in the struggle, ‘race and a sense of community’ constituted the vital power base of the strikers. Still, the rest of the Leicester white working class remained unmoved.

[7]

Unofficial walk-outs and/or strikes for equal conditions were not limited to migrant workers, for example the Heath government’s 1972 pay freeze provoked a sit-in at the Hoover factory and, in the same year, Lucas CAV workers took strike action over pay differentials. Women played a huge part in the West London factory workforce, accounting for more than half of the workforce in many factories (EMI in Hayes, Tetley Tea in Greenford etc.). Their role was noted in a sociological study by Ruth Cavendish called ‘Women on the Line’ (1977 – 78) about a West London factory employing about 1,800 people. Women workers fought for equal pay, amongst many other things.

* The Trico strike in Brentford, West London, 1976

In 1976, one of the most far-reaching equal pay strikes was successfully won at the Trico-Folberth factory in Brentford. An American company that had set up in West London in the thirties, Trico made windscreen wipers and employed both men and women who were in the AEU trade union. The 350 women ignored a tribunal decision on equal pay and stayed out on strike for twenty-one weeks, leading to the Great West Road, where the factory was located being dubbed the ‘Costa del Trico’. (Equal pay had not advanced in the private sector since 1945, despite a Royal Commission (1946), although it was introduced in the public sector in 1955).

“The best paid jobs were in factories. So I went down the Job Centre and that how I came to work at Trico, towards the end of 1975. I worked on the blades. Arms and blades, assembling arms and blades for the windscreen wipers, but they also made other accessories for the car trade, so it was one of the main employers in the area. It was quite a big factory, I mean 1,600… There had been a night-shift but because of the downturn in the economy around 1975, the company announced that they were going to close the night-shift. The men, five at all, were offered alternative assembly work on the day shift alongside the women. At the end of our 40-hour week, if they achieved the same performance as one of the women they came away with £6 – £6.50 more than the women at the same speed. That was dynamite!”

Sally Groves

“Come to the Costa del Trico

Land of laughter and wine

Take care what you do

Or we’ll cut you in two

If you put one foot across this line.

Don’t be tempted, young men

Don’t you tangle with them

For these are not commonplace

ladies

Their fury when goaded

Their wrath when exploded

Escapes like a bat out of Hades

Now you have to decide

Whether you are on their side

(…)

Cross them once you young men

You won’t cross them again

The notorious women of Trico. OLE!”

Trico closed in 1992 when the company moved production to Pontypool in Wales.

* The Grunwick strike in Brent, West London, 1976

This strike in a photo processing plant in west London is probably the most known and best documented struggle of (female) migrant workers in the UK in the 1970s. “On Friday 20 August 1976 , a group of workers led by the now famous Jayaben Desai, walked out in protest against their treatment by the managers. They joined a trade union, APEX (Association of Professional, Executive, Clerical and Computer Staff). They began to demand that Grunwick should recognise workers’ right to join trade unions.” Initially the strikers remained isolated and could not prevent scabs from entering the factory. In June 1977 the trade unions mobilised for a bigger demonstration at the factory, including the mining workers’ union. In this sense the strike marked a turning point: white Yorkshire mining workers protesting in solidarity with Asian women workers. More effective than the demonstrations was the support of postal workers in nearby Cricklewood sorting office, which processed all mail-orders for Grunwick, a vital service for the mail-order photo factory. The workers decided to boycott Grunwick mail in November 1977. This direct practical solidarity was effective, but the trade union hierarchy quickly put an end to it: they put pressure on the local union branch to end the boycott, threatening with fines and union exclusion. Similarly, the trade union hierarchy had mobilised demonstrators away from the factory gate and possible confrontations with the police. Finally, after two years dispute the APEX hierarchy and TUC slowly withdrew their ‘support’ and the remaining strikers were forced to stage a hunger strike in front of the TUC office in central London.

[8]

The main things to learn from all these disputes?

Firstly, the struggles of migrant and female workers during this period changed the face of the working class and undermined racist and gendered divisions within – more than any Racial Relations Bills or equal opportunity officers. While London dockers demonstrated for openly anti-migrant and racist politics in 1968, the struggles of migrant workers over the following decade forced the local workers to accept them as part of the class.

Secondly, most of the strikes took place under Labour governments (1964 to 1970 and 1974 to 1979), which actively imposed curbs on strike actions, not due to ‘wrong leadership’, but as managers of a crisis regime, in particular after the Sterling crisis in 1976 and the ‘adjustment programs’ after the IMF bail-out.

Thirdly, and relatedly, the strikes question the legalistic reflex of many UK trade unionists that only after the legal ban of secondary picketing and ‘solidarity strikes’ by Thatcher in the 1980s the trade union leadership became toothless. During this period in many cases of local unofficial strikes the union leadership itself interpreted and referred to the law in a way to control and contain the dispute.

*** The industrial crisis and failed attempts of ‘self-management’ – The job cuts of the 1980s

As we already mentioned west London lost 22,000 engineering jobs in 1979 – 81, representing a 17% reduction in just two years. The giant Hoover factory in Perivale (built in 1929 – 30) went from being one of the most important places for skilled engineering to a supermarket in ten years. Between 1978 and 1981 manufacturing employment at the factory fell by 67% from 1,851 to only 604 and the factory closed in 1982. During the late 1970s of seventy firms folded in Park Royal and 6,000 jobs were lost. The vast laundry sector in Acton closed by 1980 destroying another 5,000 jobs. EMI in Southall laid off 300 workers in 1980 and Heinz closed in 1993, despite an attempt by the Greater London Council to launch a rescue plan in the mid-eighties. The Firestone factory closed with the loss of 2,000 jobs. AEC in Southall and Park Royal Vehicles closed in 1978 – 79 with loss of 3,500 skilled jobs and London’s buses ceased to be made in the capital.

An example of restructuring at Kodak: Kodak employed 4,000 people in 1945 and 6,000 in 1956. The Kodak Harrow in West London factory specialised in coated photographic paper. Kodak had a library, a profit-sharing scheme and a recreational society. It did not, however, allow its workers to join trade unions, a policy that began to produce widespread friction. (…) In 1962, the unions formed a Kodak Joint Trade Union body but the company refused to recognise them for consultation and negotiation. ACTT won recognition in 1973 after a work-to-rule. The print union (SOGAT) had helped by imposing restrictions on materials; TV branch newsreel members switched consumption to alternative film stocks; T&G drivers stopped moving Kodak goods and supplies and National Graphical Association (NGA) members stopped Kodak’s house journal. (…) The Kodak union eventually agreed to join the T&G. By 1984, however, Kodak was being restructured and the factory was in danger of closure. (…) Jobs were also being cut in the USA, Germany and France. The GLC Popular planning Unit tried to support the workforce from redundancy by helping to draw together the unions of the European-based subsidiaries of Kodak. (…) But 900 jobs were lost in 1986 and production was run down leaving only about 500 staff.

The massive loss of jobs in west London did not go uncontested, but isolated actions were not able to turn the tide. In 1974, 300 ‘militant’ workers at the Cramic Engineering plant in Southall refused to accept the planned closure, rejecting management claims that it was financially impossible to keep the plant open. Lucas CAV in Warple Way, the biggest employer in Acton, was threatened with 250 – 300 job losses in 1974 and only a determined union campaign reduced the figure to twenty-five at this time.

The attempts of higher skilled engineers to develop plans for a take-over of the plant and to produce ’socially useful goods’ remained marginal. At Lucas engineering plant on Chandos Road in Willesden staff organised a six-week occupation until the company tore off the roof when it was unoccupied. Lucas Aerospace workers developed a Corporate Plan to manufacture socially useful products, amongst others, a ‘Road Rail Vehicle’, basically buses on tracks. At the time around 50% of the production of Lucas Industries was dedicated for the military sector.

In 1972 the Lucas Aerospace Combine Shop Steward Committee (SSCC) was set up to coordinate wage disputes and union work amongst the dozen different production sites. In 1974 the Combine set up a ‘Science and Technology Advisory Service’, initially to monitor changes in the production process which could lead to re-structuring. They developed links to ‘socially responsible’ scientists at universities and elsewhere. The Combine was confronted with severe job cuts during the first half of the 1970s, reducing the total workforce from 18,000 to 13,000. The Combine politically supported government cuts to the ’defence budget’, so they felt the need to come up with an alternative ‘Corporate Plan’ in November 1974. They discussed their plan with Tony Benn, at the time Minister of Industry of the Labour government. They decided on planning meetings consisting of representatives of the trade union, government and company. The Lucas engineers presented a 200 page Corporate Plan in 1976, comprising 150 new products and changes to the production process: from wind mills for ‘developing countries’ to ‘Hobcars’ for children with spinal deceases, to high-speed mono-rail trains.

In October 1975, when 400 workers at the Marston Green Electronics factory in Birmingham were threatened with redundancies due to the loss of a Multi Role Combat Aircraft contract from the UK government local shop-stewards presented an alternative corporate plan – but after a contract for control panels for a Russian aeroplane was obtained, management was able to sideline them. In Hemel Hempstead a similar situation had occurred in June 1975, where shop-stewards countered a redundancy plan with their own ‘market research’, but only mass meetings of 2,000 workers and the open threat to occupy the factory and to engage in a ‘work-in’ was able to reverse the redundancy plan (without actual changes to the production process or product line).

[9]

“When we were at Lucas Aerospace we were in a pro-active situation. We were making plans based on our predictions of structural unemployment arising from technological change. Lucas was important because it was the first time that the idea that workers should have a say in what is made in their factories was developed collectively. Alternative plans give workers extra strength. We used the Lucas Plan as a bargaining point with management. But we also took it further than that. We said the company had to take on the socially-useful products as well as the profit-making one.”

Ernie Scarbrow

As the lobbying of Labour Party MPs and Union bosses continued, Lucas’s management proceeded with the job cuts and rationalisations where they could. With the SSCC busy lobbying but not co-ordinating any action, unity weakened among the workforce. Different areas were left to fend for themselves.

For us the experiments at Lucas are still valuable lessons, which we should re-consider in these times of crisis. The company was not producing ceramic tiles or soap – like some of the current ‘self-managed factories’ – but thanks to the productive knowledge and means of production workers were potentially able to plan and manufacture things which capitalist profit production would neglect or not even consider. At the same time the Lucas experience demonstrates the fact that ‘workers’ control’ is not primarily a technological question: for the highly skilled Lucas workers, who were able to draw up technical and economic plans, the main partner they addressed were those ‘political engineers’ in government, who could provide them with a national plan to finance their production. This mainly reflects the divisions within the working class, between those workers who participate in the intellectual planning work and those who merely ‘operate’. As a former Lucas worker said:

“Having worked at Lucas from 1959 to 1990, I find […] the ‘Engineers’ were dominated by the skilled men, who in many ways were the tyrants of the shop floor and ignored the demands or requests of the women for equality or the lower paid in general. When we consider that the voting was by union and we had Tinsmiths and Electricians, plumbers, the unskilled were out voted, indeed they barely surfaced. The annual wage claim for years was across the board, which meant that the unskilled were losing ground yearly, yet the pretence was that it was an equal claim. It was only when a TGWU, shop steward pointed out that 6% of £100 was scarcely the same as 6% of £200 or 300? The comrade was met with an attempt by the AUE, branch chairman, a left winger on the district committee, to stop him talking to the workforce! Later, the Drivers, (T&GWU,) came with a plea for parity with the skilled sections. This was opposed by the Senior Shop Stewards Ctte, who actually banned the T&GWU delegate from the S.SS.C., when a stich up was agreed to by the Lucas management. Not that he had broken any rules, but that he had offended the skilled men by gaining parity! […] In the sixties or seventies agreement was reached between the SSC and management for a bonus! It was to be paid through the wage, but not to the canteen women, or the safety / firemen. Why? They didn’t produce! On the factory floor very few people produce, most make production flow smoothly,i.e. Semi-skilled inspectors, labourers, drivers and so on, but without them production becomes hard and slows down. Why were the firemen and the ,canteen women,’discriminated against?”

[10]

For a communist organisation at the time it would have been a challenge to develop a strategy to combine the direct combativeness of, for example, the female assembly line workers at Chix bubble-gum factory in nearby Slough, and their criticism of the factory regime, with the productive knowledge of engineering workers, such as at Lucas. The wave of factory struggles of lower skilled (migrant and female) proletarians ran parallel to the dispute and planning at Lucas. We don’t know if and how they influenced each other, but the fact is that the Lucas workers reached out to the Labour government, rather than developed a plan within the wider class militancy.

What can we generally conclude from the 1980s? It would be easy to draw up an apocalyptic picture of de-industrialisation: the Hoover factory turned into an art-deco mega Tesco supermarket, the closed Guinness brewery and other industrial units in Park Royal became sites of squat parties during the raving 1990s. The working class became a class of house owners and the former militants of the anti-racist migrant workers mobilisations turned into funded community leaders and local MPs… but it is obviously not that easy. Before we have a brief look at the 1990s we would like to contrast the symbolic image of a closed factory in Park Royal covered with graffiti and fake Detroit techno with a different picture, which one of us took at work in Park Royal in 2016.

The picture is taken inside of a factory in Park Royal. It is not an engineering plant or a factory manufacturing car parts, as it might have been in the 1960s or 70s. It is a site of precarious production: downstairs 180 mainly female migrant workers, most of them women from Kenya-Gujarat and Goa sort and re-fill ink cartridges with basic industrial machines. Upstairs, where the picture has been taken, a dozen male workers assemble 3D-printers on a Polaroid sub-contract. The company pays the young engineers, migrant workers from Asia, who have spent £36,000 on university fees for their mechanical engineering studies a lousy £15,500 per year. The company re-cycles not only ink cartridges, but also ex-colonial relations and – here comes the symbolism! – industrial trays which has formerly been used in Lucas Burnley factories in Park Royal – as can be seen in the picture. In 1972 after a 13 week strike by Lucas Burnley workers enforced a wage increase 167% larger than that nationally negotiated by the union officials. The management of our 2016 reality must have bought these industrial trays cheap somewhere and now these symbols of former ‘workers’ productive pride’ are used as containers for precarious 0-hour labour which probably none of those preachers of ‘post-industrialism’ would recognise as factory work.

*** The Logistical Productive Shift – from the 1990s onwards

While it was canals in the 1900s and the extension of the western railway in the 1930s it was the expansion of Heathrow airport during the 1980s and 1990s which not only created local jobs, but also re-shaped the wider logistical network: fresh produce, parcels, electronic parts arriving in the belly of tourist passenger machines are sorted and packaged in dozens of warehouses and distribution centres. Depending on political outlook Heathrow airport employs directly and indirectly between 80,000 and 150,000 people – most of these are manual jobs – more than the local engineering industry ever did.

Unsurprisingly, the new concentration of workforce has led to conflicts, e.g. at the airline caterers LSG in the late 1990s and Gate Gourmet in the mid-2000s. These disputes were not dissimilar to some of the factory struggles in the 1970s, in particular the relations between strikers and union hierarchy.

* LSG, Southall, 1998

LSG tried to force their workers in Southall to sign new, worse contracts. The workers, most of them T&G members had two ballots before taking official strike action. On the first day a court injunction prevented them from going ahead. Management then sacked 200 workers on the second strike day and hired new ones. The company’s video cameras filmed the pickets at the gate: when strikers photographed scabs the police threatened them with arrest for “intimidation”. Only a few of the original workers got their jobs back, after months of symbolic pickets and legal show-fights. The T&G union only gave lukewarm support to the workers – at the time the TGWU had thousands of members at Heathrow airport, but the union tactically decided not to call other workers out for support – they didn’t want to risk of a confrontation with the law or with the New Labour government at the time.

* Gate Gourmet, Southall, 2005

In the 1990s, British Airways (BA) outsourced work to Gate Gourmet. In August 2005 management wanted to enforce a worsening of conditions and one day brought in agency staff, factually replacing permanent workers. The old workers met up in the canteen to discuss and to protest against this move. In response management sacked over 800 workers over the next two days. An unofficial walkout by BA ground staff – mainly baggage handlers – at Heathrow airport in solidarity with the Gate Gourmet workers resulted in a 48 hours closure of the airport. But the baggage handlers had to return to work – the TWGU union did not want to be associated with ‘illegal’ support strikes. In the end the union told workers to sign contracts with worse conditions.

[11]

Not only has the infrastructure changed, so has the workforce. From the 2000s onwards Perivale, Greenford and other parts of far-west London have seen the arrival of many eastern European workers, who now account for more than half of the work-force in many warehouses and production units, together with recently arrived workers from the sub-continent. Many of these workers from Poland or Romania know little about the history of ex-colonial migration and their own racist prejudices mix with the fact that by now many of the middle managers, landlords and small business men are ‘old’ Asian migrants from the 1960s and 1970s and/or their children.

These workers work in workplaces and ‘industrial parks’ different from the 1970s. Park Royal as an industrial area has changed a lot – as you can see on the ‘Park Royal Atlas’, recently published by the Greater London Authority. The study claims that there are 1,717 active companies situated in Park Royal, employing around 31,000 people – which means that the average workplace has around 18 workers. Only 1%, meaning around 20 companies, employ more than 250 people, most of these are food production plants. Further 4%, meaning around 70 companies, employ between 50 and 250 people. We would reckon that the average size of workplaces were greater four decades ago.

[12]

Also the composition of companies has changed, there are many small offices, sound studios, warehouses, small garages, glass or electronics production units and places where you couldn’t guess what is happening inside, e.g. assembly work of 3D-printers. Around 70% of the total floor space in Park Royal is dedicated to warehouses. New warehouse units have been developed by the ‘logistics developer’ Segro, e.g. for John Lewis or Ocado. Below we quote the ‘Atlas’ survey giving examples of what has been produced annually in Park Royal. It shows that the working class in Park Royal combined has an enormous productive and creative capacity.

40,000,000 plumbing fittings manufactured – 30,000 domestic removals completed – 90 online interactive magazines created – 24,000 books sold to university libraries – 5 residential development projects delivered – 8,500 book-related events organised – 25,000 units of tools and equipment rented – 1,400,000 postal and freight deliveries – 12,000 lorries repaired – 2,000 custom print jobs delivered – 7 full length studio films processed – 240,000 bouquets of flowers sold – 15 cars converted to ambulances – 7,200 sales of music equipment effected – 94,000 hotel guests accomodated – 3,000 hires of recording studio – 42,000 hospital patients transported – 1,500 stage and film lights rented – 500 tonnes of coffee delivered – 300,000 sushi rolls produced – 500,000 tonnes of building waste processed – 2,000 sqm of natural stone tiles sold – 100,000 natural sea sponges sold 1,000 pallets of Balkan food imported – 3,900 tonnes of laundry cleaned – 1,000 tonnes of nuts roasted – 50 tonnes of steel processed – 1,000,000 hygiene tests conducted – 600,000 ink cartridges re-filled… this doesn’t include neither the patients cared for at Park Royal hospital, nor the tons of Moussaka assembled at various Bakkavor factory conveyor belts…

What we need now is our own inquiry, not into the business size and commercial prospects, but in the underlying class anger and potential to organise in future. Feel free to join us in our explorations…

AngryWorkers, May 2016

angryworkersworld@gmail.com

Footnotes:

[1]

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol3/pp212-215

[2]

http://www.labour-heritage.com/The%20Roots%20of%20Labour.pdf

[3]

http://www.morningstaronline.co.uk/a-f88a-Extraordinary-lives-and-times#.VyXS_Lynui4

[4]

http://ourhistory-hayes.blogspot.co.uk/search/label/Southall

[5]

http://www.labour-heritage.com/Bulletin%20Autumn%202004.pdf

http://libcom.org/files/ambalavaner-sivanandan-from-resistance-to-rebellion-asian-and-afrocaribbean-struggles-in-britain.pdf

[6]

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=ur_n_kjoeE8C&pg=PA37&lpg=PA37&dq=Harwood+Cash+strike&source=bl&ots=XoBnouAEex&sig=NraVKE0QHTMYN4RfkjMiuAiwQwE&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjMtJDd57jMAhXDHR4KHfYOBTgQ6AEINDAE#v=onepage&q=Harwood%20Cash%20strike&f=false

[7]

[8]

http://www.striking-women.org/module/striking-out/grunwick-dispute

http://en.labournet.tv/video/6528/year-beaver

[9]

http://digital.library.lse.ac.uk/objects/lse:baq928jod

http://www.workerscontrol.net/authors/lucas-plan-what-can-it-tell-us-about-democratising-technology-today

http://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/28095/1/strathprints028095.pdf

[10]

https://libcom.org/history/articles/lucas-aerospace-fight

[11]

http://www.striking-women.org/module/striking-out/gate-gourmet-dispute

[12]

https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/Park%20Royal%20Atlas%20Screen%20Version%201.1_0.pdf