While it didn’t make massive news headlines, the industrial dispute at Liverpool university against 47 compulsory redundancies certainly counts as the second largest disputes of this century in Merseyside (after the protracted battle of the RMT train guards on Merseyrail in 2017-18). It is certainly the most important dispute in higher education. The UCU union branch at Liverpool university came up with a combined strategy of two strikes lasting 24 days and a marking boycott in between, that strategically hit the employer during two sensitive periods: when students receive their degrees, and during the week of student recruitment. The strategy worked. The employer backed down and only two compulsory redundancies remain on the table. The latest mass branch meeting voted by 82% for another industrial action that will be soon publicised. In this article, a participant in the dispute looks at it from the point of view of higher education workers as a totality and reflects on the barriers to generalisation of class conflicts across the sector.

Around two years ago, the University of Liverpool (UoL) announced a major restructuring of the Faculty of Health & Life Sciences (HLS). ‘Project SHAPE’ was the name given to the process of ‘collective consultation’. The staff were repeatedly assured by the new pro-Vice Chancellor, Louise Kenny, that no one would be made redundant. She also emphasised that the reform was not driven by cost-cutting aims. Despite warnings by the UCU union, many staff keenly took part in the university’s consultation, naively supplying their own performance data and even feeling proud that they were finally being taken seriously by the top UoL management.

The announcement of 47 redundancies in the HLS as part of Project SHAPE in January 2021 was a real bombshell for these academics. People could not believe that, despite the fact that they “had done everything that was being asked of them”, they were suddenly being put on a list of under-performers. UoL used inappropriate grant income thresholds, which were so high, that more than half of the staff at the Russell Group of universities would not be able to meet them. The trick was two-fold: first, they wrongly classified HLS staff so that the majority fell into clinical categories, who are expected to bring in the highest amounts of research income. Secondly, they used mean grant income from the clinical science sector as an individual threshold for everyone, which then increased the target for most Faculty members. The result was that even some of the most research-intensive psychologists were unable to meet the threshold and ended up on the redundancy list. (Details here).

These dubious metrics made it pretty easy for the UCU branch at Liverpool university (around 1500 members out of 7000 university staff, the largest union at UoL) to challenge management, and even galvanise large professional support from the world’s major metrics organisations. My UCU Branch Committee (UCUBC) sensed a great opportunity to publicly discredit UoL and put them on the defensive. However, this opportunism opened up a path that was not really helpful from a trade union point of view. The core of all UCUBC arguments against these 47 redundancies became inscribed in this technical issue: the wrong metrics had been used, and in the wrong way. This argument has been plastered everywhere, from simple twitter slogans through to numerous professional and open letters and articles, such as this detailed analytical document exposing the failure of Project SHAPE, published by UCUBC.

A brief summary of the dispute.

In March we balloted: turnout was 60% (around 900 members), of which 84% (around 750) were in favour of strike, and 90% in favour of ‘Action short of strike’ (ASOS). On May 10th 2021, we began ASOS that consisted of the following:

- Working to contract

- Not covering for any absent colleagues or vacant posts

- Not undertaking any voluntary duties.

During the ASOS, we heard from colleagues in the HLS that the list of redundancies was shortened from 47 to 32 jobs, which indicated a certain power coming from the strike threat we were wielding.

The strike lasted three weeks, from 24th May to 11th June. We had daily strike meetings on zoom and small pickets on the campus. On some days, some striking lecturers volunteered to do the usual ‘teach-outs’ (as during every strike recently). [1] There was also a “strike picnic” in a park every week, and one on-campus rally a week. The UoL Vice-Chancellor, (the top boss who ‘earns’ £410k a year!) Janet Beer, informed all staff via email that, according to HR records, only 335 staff were on strike. This was almost certainly an under-statement due to the fact that some members missed the deadline for logging in their strike days. But even if the correct number was 400-450, this was still a relatively low number when compared to the fact that approximately 750 workers voted in favour of the strike.

During the strike, on the 1st of June, we had an Ordinary General Meeting (OGM) where we voted for an escalation of the dispute if compulsory redundancies were not going to be withdrawn. We wanted to start a marking boycott as soon as we had received formal approval at the national UCU level and after the legal 2-week notification to the employer. [2] However, all of the typical legal procedures and restraints caused a delay in implementing it, meaning that it didn’t start until a week after the end of the strike. This was criticised by several members in our meeting, but accepted as a necessary bureacracy. In the meantime, people had to return to work but on a go-slow, adhering to the rules of ASOS. The motion (passed in the OGM) on the marking boycott also declared that if the staff involved in the boycott were going to have 100% of their pay docked, the non-marking members would donate 50% of their wage to help sustain the boycott to last as long as it would take.

The SLT planned to employ scores of external examiners to mark the students’ work. If that wouldn’t work, they wanted to appoint a single examiner per School or Faculty to mark all the work! Branch members were really shocked at how far the SLT were willing to go, and how easily they were ready to drop any pretence at academic quality and integrity – what the academics perceived as ‘undervaluing’ students’ degrees.

This massive scabbing scheme, however, was only partially successful. This was due to an extensive lobbying exercise by the UCUBC, and many ordinary members, where workers used social media and personal correspondence to their academic contacts across the country and the world, informing them of the dispute and asking them not to get involved in examining. This tactic worked to the extent that Heads of Schools and Deans were found secretly marking students’ work over the weekends (although ‘marking’ is an over-statement, more like just signing off whatever they could access on the online portal). Unfortunately, in some departments, scabbing was done by the workers not involved in the boycott themselves, which undermined the effectiveness of the tactic. Some strikers were brave enough to boot the scabs out of the online marking spaces such as ‘CANVAS’, but I don’t know how many actually did it against the directives of the Heads of Departments who told them not to. (Also, the scabs were continually re-added to CANVAS the following morning, so it was a tiring, if impressive, game of cat-and-mouse!) On the one hand, these things lead to resentment and antagonism between colleagues. But, on the other hand, they built stronger bonds between the strikers, and some colleagues even chose to join the union then, precisely to avoid managers’ pressures to sabotage the strikers.

On Monday 5th July, ‘Results Week ‘ started, and it was leaked that 1500 students had not received their marks, while others had only received some. The success of missing marks varied between departments: some reached about 50% of students, but it was a bit less in most cases.

As the marking boycott was taking shape and we could see the strong resistance by the SLT, the UCUBC convened an Extraordinary General Meeting (EGM) where we voted for a further escalation in the form of a strike during the critical period in the lifecycle of a university: the Clearing and Confirmation week in early August. [3] The choice of this course of action was preceded by a discussion among the strikers as to what the ‘pinch points’ in the university were, in other words, where they were especially vulnerable. The strike targeting the clearing process was going to be critically dependent on the refusal of labour by the Admissions staff, some of who are in UCU and some in another union. [4]

In every prolonged industrial dispute, moments arise when the enemy tries to catch the workers by surprise and scare them into submission. One such moment arose when the SLT sent an email around informing us that they would deduct 100% pay for the partial performance of those on the marking boycott, a measure that would immediately throw Liverpool SLT among the few most aggressive university managements in the UK. Any work-related activity conducted by boycotters during the boycott, the email continued, would be considered “voluntary and unpaid!” In this crucial moment, the strike leadership in our UCUBC stood their ground and replied bravely to this provocation. UCUBC asked the boycotters to stop working entirely because, “as a union, we can’t condone free labour”. So the managerial idiocy actually helped the union to test-drive on a new and fuzzy terrain: officially they were facilitating a marking boycott that had de facto turned into an informal strike with a couple of hundred participants, while hundreds of others without teaching/marking roles engaged in various forms of ASOS! Despite very bolshy weekly emails from the SLT and the VC to all staff, attempting to minimise the disruption and promising quick fixes to the missing marks and degrees, the reality was obviously worse for them than they were admitting. So, on Friday the 9th July, the SLT sent out a surprising email to all staff where they proposed to suspend the 100% pay deduction for two following weeks – if the UCU would agree to negotiations.

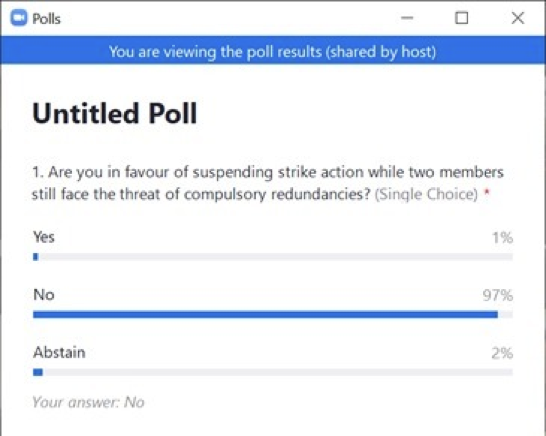

To cut a long story short, as the marking boycott continued to bite and there was no sign the staff were bothered about the SLT calls to “prioritise the welfare and careers of students”, the university management went into a panicky reverse gear: during July, the number of redundancies was pushed down to 21, then to 7 (from the initial 47). When, after a meeting between UCUBC negotiators and the SLT it became clear that the strike planned for the critical Clearing period (4-14th August) was going ahead, the SLT came up with the final offer of only two compulsory redundancies. The enemy retreat and the awareness of a fast-growing strike fund (from £6k in May to over £120k in August, mainly through donations from other UCU branches) encouraged the strikers to hold the line. So, the EGM meeting on the 3rd August voted against suspending the strike action (97% of the 234 present) to fight for the remaining two jobs.

It is unclear to me how efficient the strike during the Clearing period, 4th to 14th August, was. The SLT did not budge from their ‘final offer’, and two compulsory redundancies are still on the cards. However, I remember that when the plan to attack the Clearing and Confirmation period was voted on, a branch member working as an ARPS (Academic-related Professional Services, a non-academic part of UCU membership) warned that some of his colleagues who are in UNISON could easily cover the work of strikers in the Clearing process. This risk was dismissed by the Branch leadership, who said that we would coordinate with this crucial section of the strikers to ensure maximum disruption. From the outcome of the strike (no progress) I assume (without real confidence) that the disruption was not effective enough, and some of the critical labour was, unfortunately and involuntarily, scabbed…

Questions and problems

There are some limitations worth mentioning which we find at both local and national level in the UCU and some other unions too.

- An inefficient way of conducting industrial disputes

The anti-union laws seem to leave a very small margin for a union to move. Any disruption other than withdrawal of labour is straightaway criminal, and the UCU would never condone it. On the other hand, in order to make the withdrawal of labour really impactful, we need to stop or reduce the scabbing, and this is seen as disruptive and illegal by both the law and the union.

The online way of working and striking during the pandemic makes industrial disputes even less efficient. Workers are separated in their homes, and it is easy for the management to approach students online and organise scabbing. You may say, “What are you going on about? The strike and the marking boycott worked, look at the results!” Yes, they did work, but how efficient was it? Would we have lost less wages if we’d have done a short strike in combination with a quick disruptive direct action that could have brought much of university business to a halt? These things really matter for the precariously employed section who work on part-time, short-term or zero-hours contracts, who have sacrificed proportionally much more than permanent colleagues on higher bands,with accumulated savings etc.

Are scabbing, undermining the standards of marking and other ‘counter-insurgency’ tactics by the SLT signs of the further deskilling of academic work? Does it erase the remnants of their autonomy and increase academics’ ‘proletarianisation?’ I think this would be the case if the UCUBC recognised and openly rephrased the strikes in these terms, rather than falling back on the defence of the ‘amazing scientific value’ of the colleagues at risk. Materially speaking, such a proletarianisation is well underway, but it needs to be reflected subjectively too, rather than by supporting the elitist illusions of some of the colleagues.

- No ambition to coordinate UCU struggles nationally

UCU is reporting 28 defensive disputes at various stages nationally (against departmental closures, compulsory redundancies, restructuring projects or just various stupid managerial decisions). And yet there is no movement towards a national unification of these struggles. The same is also true for UNISON in ‘Higher Education’, where the national conference decided that balloting on strike action against pay freezes would best be conducted by every branch separately, rather than in a single national ballot. I think this shows that the UCU has adapted itself to the fragmented and highly unequal ‘marketised’ landscape of British academia.

In 2015, the government got rid of the cap on student numbers that had been imposed up until then, which only increased competition between universities to capture as many students as possible. This meant even larger investments into physical infrastructure and rental accommodation. Financially weaker universities have to rely on massive programmes of borrowing just to keep afloat. That is the main cause of the sector’s overall debt trebling in a decade, to £12bn in 2018. Even between the UK’s 20 largest universities, the combined debt has increased 50% from £6.3bn to £9.5bn over the last five years. Whilst the debt spiral has been accelerated by the pandemic, it has largely been driven by the major infrastructure projects by universities, mainly consisting of buying and building properties for student accommodation.

Demand for accommodation and student services has also increased, as student numbers have risen by 3.2% to 2.46 million in the UK in 2019/2020. Universities have channelled massive investments into these areas, and had to increase their borrowing to do so. (Raising private finance has only further locked universities into the mad spiral of “market-conforming” behaviour – maintaining their credit ratings, committing to a continuous flow of students and their fees, and a hawkish approach to cutting wage costs wherever possible).

Given this background, the conditions for class struggles in the lecture halls are extremely unequal. The union branches operating in financially stronger universities are usually in much more favourable situations than those in universities struggling under piles of debt and restructuring programmes enforced by the creditors. These material differences are sometimes directly reflected in workers’ different levels of readiness for struggle. While it was relatively easy for union activists to drum up high levels of support for the 47 colleagues in Liverpool, where hardly anyone believed in any economic rationale behind this attack, the story at Leicester university was entirely different. Leicester University is currently engaged with some of the riskier American financial creditors and securitisation instruments, which raised its long-term liabilities to an incredible £250 million. Add to that a £60 million Bank of England ‘pandemic’ loan that needs to be paid in 12 months, and the managerial solution was obvious! Since January, 115 members of staff have been made redundant.

In contrast to Liverpool, their restructuring project had an openly political undertone: out of 26 redundancies scheduled for August, many were local UCU activists and ‘Leftists’. They were targeted for academic work that discusses ‘radical alternatives’ and for “questioning the authority of mainstream management thinking and practice…” Unlike in Liverpool, the branch union membership base showed much less appetite for real battle: three days of strike action in early June followed by a marking boycott that only small minority took part in. The bleak prospects were finally sealed on the 9th August when, at the UCU branch meeting, 59% voted to stop the marking boycott and accept the managerial offer (no pay deductions for the ASOS action, no further redundancies in stage 2 (“if possible…”).

The comparison between the two struggles is important!

| Financial situation | Restructuring target | Political characteristics of the target | Result | |

| Liverpool (47 redundancies) | Strong (£6 million operating surplus after pandemic dip) | Mostly clinical & applied scientists generating hard research income | School of Health & Life Sciences rather apolitical with little union density until 2021 | Effective action supported by membership base throughout |

| Leicester (140 redundancies) | Weak (£60 million short-term loan) plus more long-term debts | Critical humanities scholars not seen as valuable by the market | Leading UCUBC activists, members of the radical left | Increasing isolation of UCUBC activists leading to defeat |

The other, secondary, dynamic that perpetuates lack of national fightback is the competition inside the UCU itself. Since the national 14-day pension strike in 2018, a new faction has formed and won the national leadership positions. This faction is generally made up of younger workers who have not been schooled in the traditionally strong UCU Left faction and have a more open way of doing things. Most of this faction are broadly to the left of the SWP/Trotskyist politics that dominate the UCU Left faction. While the affiliations are not clear cut, some branches (or rather UCUBCs) tend to be under the influence of one or the other. However, discussing these differences inside the union is beyond the scope of this text.

- Expanding the struggles

“When you will be bullied by your manager, you come to the Committee, who are skilled people that deal with that sort of thing.”

This is a standard refrain to explain how a UCU branch deals with stand-offs between unfriendly bosses and workers at the level of particular departments. Despite UCU sending its activists to Jane McAlevey’s organising courses, the union still uses every opportunity to insert itself as a necessary mediator into the smallest micro-conflicts. So, collectivising workers’ responses to bullies for example is discouraged because of the risk of ‘breaches of work contract’, rather than encouraged with the strategic view of building a stronger union through grassroots power across departments. Should the efforts of militant university workers therefore aim at fighting for an organising model (McAlevey) of trade unionism? I think blowing fresh oxygen into a pond that’s structurally shrinking year by year can only get us so far. Instead, we need to fight for a larger space for workers’ action, which effectively means going against the current clock set by financialisation, restructuring and fragmentation (material, legal, cultural).

Luckily, the pandemic in 2020 showed the scale of workers’ power that, in ‘normal’ times, remains less visible. Achieving and consolidating the transformation to the new, online model of teaching was a huge logistic exercise that required coordination and collaboration of the whole collective university worker. Lecturers needed to prepare the online content, the fixed-term-contract workers did the marking and exam resits later on, organised the “virtual” open days, etc., procurement workers were commissioning external digital content providers. IT workers were essential to test, run and maintain the new online teaching platforms. Cleaners became unofficial public health workers, ensuring frequent disinfection of surfaces and common spaces. In short, in 2020 everyone in my branch realised (as was said many times in meetings) that it was the collective university worker who saved the whole institution, despite the mess that the top dogs were able to inflict on everyone. The economically meaningless recent attack on the Health and Life Science workers at Liverpool university can therefore be seen as a political action: to put the control back into the managers’ hands after they had twatted themselves big time. Or maybe management felt they could press their advantage in a situation where workers on the whole rose to the challenge and kept working during the pandemic – why not take the piss a bit more and save some money at the same time? Who knows…

During the pandemic emergency in 2020, neither of the three unions dared to call for a mass assembly of all university workers. Translated into the language of the Italian operaismo, the technical composition of the class was made visible without being transformed into a political composition. The chance to seize the moment for more workers’ control has gone. But the memory hasn’t – and there are new challenges ahead of us. As already mentioned, UCU is already involved in 28 defensive local disputes to stop various cuts. Next week it is also relaunching its frozen Four Fights campaign (pay rise, workload, gender/ethnic pay gaps, casualisation) and the fight against the 35% pension cut. Unison is balloting its Higher Education members for a strike against the pay freeze. If various particular campaigns and disputes, involving universities’ scientific and mass workers, cross their paths, the collective university worker may arise again, and a mass assembly could provide the platform to exchange and coordinate actions.

——

1 ‘Teach-outs’ are essentially workshops and seminars that are organised by workers and students during industrial disputes in Higher Education. The general idea is that of providing a sort of radical educational experience outside of the logic of the academic institutions.

2 In Higher Education, boycotting of marking students’ work has sometimes been used as a tactic by workers in disputes. The reason this is effective is because of the general way in which universities act as a factory that produces ‘qualified’ workers. If these qualifications can’t be ratified with tutors’ signatures, the university has failed to produce one of its primary products and risks both “reputational damage”, and withdrawal of some investments from corporations and firms who use particular pools of graduates as their primary recruiting pool.

3 This is the time when prospective students get their A Level results and universities engage in a general scramble to mop up the unlucky bunch who didn’t “achieve high enough grades” to secure a position in their first or second choice institutions. It is a period of time where universities like to look their most squeaky-clean. After all, each kid is worth almost 10 grand of possible collateral for infrastructural investments!

4 Administration and Professional Service workers in universities are often divided by pay-grade when it comes to which union represents them. UCU tends to include the higher paid workers for some reason, whilst UNISON covers the more background, lower paid workers in these areas.