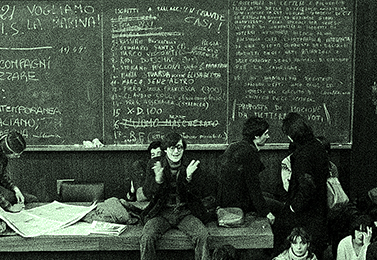

We document this great pamphlet, written by comrades in France, on the relation between working class autonomy and the government during Allende in 1973:

We also recently listened to Bhaskar Sunkara presenting his new book with the modest title ‘The Socialist Manifesto‘ at Red Emma Bookshop [1] and Novara Media [2].

For various reasons which we’ll talk a bit more about later on, we think that parliamentary politics are a dead-end. But we appreciated Sunkara‘s talk as being one of the most concise presentations of current political positions which propose a parliamentary road to socialism. We appreciate the effort to look for strategies which examine all tools that the working class has in their struggle against exploitation. We can understand the attraction of this type of strategical thinking – instead of clinging to utopias or preaching stale positions the new generation of ‘democratic socialists‘ tries to grapple with what‘s in front of us: a weakened labour movement, a detached social movement, a capitalist crisis, a de-legitimatised political class, the emergence of small-scale and potentially cooperative enterprises and a re-emergence of a parliamentary left which is not afraid to use the word socialism. The challenge seems to be to create the right relation between movements from below and the parliamentary institutions which could secure and expand gains that movements have achieved in struggle. Sunkara looks at historical examples – from the Russian Revolution to Swedish social democracy in the post-World War Two period to find some clues.

We don‘t have the time to properly engage with the main arguments here and now. Instead we want to refer to a pamphlet written by comrades of ours about class struggle and the social democratic government under Allende in Chile in 1973. Chile is one of many examples in history that shows us that the relation between working class movements and left governments is more complicated than the often mechanistic picture of force (movement) and container/stabiliser (government). We can see that the initial social reforms were introduced by a right-wing government, which failed to contain class struggle. When Allende took over he had a hard time to keep workers‘ and poor peoples‘ struggles under control – struggles which might well have been encouraged by the incoming left government. Allende feared that the local bourgeoisie and international imperialist forces would use the social turmoil as an excuse for intervention.

International price developments, in particular of mining products, curbed the scope for material concessions towards striking workers. Allende’s policies towards the proletarian unrest – which ranged from concessions to military repression – undermined and literally disarmed the working class. When the local military, backed by the CIA, went in for the kill, the resistance was already weakened. This paradoxical relationship between class movements and left governments is not something peculiar to Chile – Robert Brenner describes it as a general paradox of social democracy. [3] Whoever hasn’t watched the documentary ‘Battle of Chile’ yet, the second part has gripping footage of the conflict between workers who want to further the take-overs of private companies and those who want to give Allende time and avoid further clashes with the bourgeoisie. [4]

Before we let you read the pamphlet we want to make some short general points why we think that the parliamentary road leads to an impasse – to be systematised and elaborated on in the future:

1) This is not a historic phase for social democracy

Historically social democracy developed during phases of economic upturns, based on a relatively strong national industrial production capacity. What we face now is an economic crisis and an internationalised production system. This limits both the scope for material concessions and for national economic policies. We face harsher conditions of struggle than democratic socialism prepares us for.

2) Parliamentary power and state power are two different things

The idea of a parliamentarian road towards socialism neglects the fact that ‘taking over government’ and ‘having state power’ are two different kettle of fish. There is little analysis of the actual material and social class structure of the state (administration, public servants, army) and its independence from parliamentary democracy. Despite changes to its outer form the material core of the Russian state apparatus (i.e. social strata of people employed in carrying out state functions) reproduced itself from the time of the Tsarist regime, through the Bolshevik revolution, Stalinist terror, Glasnost to Putin.

3) Class struggle doesn’t develop gradually

Believing that class struggle is based on ‘step-by-step’-organising and mobilising, left political practice often puts stumbling blocks in the way of future waves of struggle. In the short-term getting ‘community leaders’ or your local MP involved, or relying on the trade union or party apparatus in order to mobilise or encourage fellow workers, might seem beneficial. Historically class struggles develop in leaps and bounds – in a much more complex dynamic between ‘organising’ and external forces and factors. What initially seemed a stepping stone turns out to be a stumbling block: for example middle-men who get in the way of things or illusions in symbolic forms of struggle. The challenge is to find ‘step-by-step’-forms of struggle which help in the moment, but don’t pose problems long-term.

4) The trade unions and the workers party are not the working class

The ‘democratic socialist’ perspective relies on the idea of a transmission between the working class and the state through interaction of the two main ‘workers’ organisations’ – the parliamentary party and the trade unions. This perspective relies on an idealistic or pre-historic view on trade unions as ‘democratic representation’ of the class. Plenty of historical examples (Labour/TUC in the UK in the 1970s, CC.OO in Spain after Franco, Solidarnosc in Poland after 1981, PT/CUT in Brazil recently etc.) demonstrate that during the heat of waves of struggles the trade union/government connection becomes the heaviest blanket on working class initiative.

5) By focusing on workers as citizens and economic levers ‘democratic socialism’ neglects their position and divisions within the social production process

In their strategies ‘democratic socialists’ treat workers either as voting citizens or as a collective economic force to put pressure onto the political arena. Their understanding of class is largely economistic – defined by the fact that workers all depend on wages. This understanding of class doesn’t focus on the actual form of the production process and its hierarchical division of labour (intellectual and manual workers, productive and reproductive work etc.). A mere change in government or a shift from private to state property would not touch the core of what defines working class, its power and disempowerment.

6) The focus on the ‘political arena’ saps energy

The governmental politics of 21st century socialism in Latin America and their structural weaknesses have created widespread disillusionment. The subjugation of the Syriza government has closed, rather than opened spaces for the class movement against austerity. The internal power-fights within Podemos or Momentum has created cynicism and burn-outs. The media hype of Corbynism diverts focus from daily struggles for working class self-defence.

7) Strategy starts from actual struggles and actual potentials and difficulties imposed by the social production process

We need strategies and we need organisation. These should focus on the objective conditions for class struggle – changes in how work and reproduction is organised, crisis in the economy and state mediation – and the subjective experiences – the actual struggles and the gap between realised class power and potential for expansion. To find organisational forms that make the best of worldwide proletarian migration, supply chains, sharp differences between developed and under-developed regions etc. is the real strategic challenge. To create organisational links between experiences of ‘appropriation as survival’ (squats, piqueteros etc.) workers’ control’ and cooperatives and ‘modern centres of industrial power’ is a precondition for the development of a revolutionary plan. [5]

Click for the pamphlet here: rendez-vousavecZEnglish

—————

[1]

[2]

[3]

A bit wordy, but this quote by Robert Brenner hits some of the nails on the head.

The point is that most of the U.S. left, like most of the left throughout the world, still remains transfixed by social democracy’s passive mass base, its left paper programs, and its historic association with reform. They refuse, therefore, to take social democracy seriously as a distinct social and historical phenomenon — one which represents distinctive social forces and, as a result, advances specific political theories and strategies, and, in turn, manifests a recognisable political dynamic within capitalism.

Since the end of the nineteenth century, the evolution of social democracy has been marked by a characteristic paradox. On the one hand, its rise has depended upon tumultuous mass working-class struggles, the same struggles which have provided the muscle to win major reforms and also the basis for the emergence of far left political organizations and ideology. The expansion of working-class self-organization, power, and political consciousness, dependent in turn upon working-class mass action, has provided the critical condition for the success of reformism as well as of the far left. On the other hand, to the extent that social democracy has been able to consolidate itself organizationally, its core representatives —drawn from the ranks of the trade union officials, the parliamentary politicians, and the petty bourgeois leaderships of the mass organizations of the oppressed — have invariably sought to implement policies reflecting their own distinctive social positions and interest — positions which are separate from and interests which are, in fundamental ways, opposed to those of the working class. Specifically, they have sought to establish and maintain a secure place for themselves and their organizations within capitalist society. To achieve this security, the official representatives of social democratic and reformist organizations have found themselves obliged to seek, at a minimum, the implicit toleration, and, ideally, the explicit recognition of capital.

As a result, they have been driven, systematically and universally, not only to relinquish socialism as a goal and revolution as a means, but, beyond that, to contain, and at times, actually to crush those upsurges of mass working-class action whose very dynamics lead, in tendency, to broader forms of working-class organization and solidarity, to deepening attacks on capital and the capitalist state, to the constitution of working people as a self-conscious class, and, in some instances, to the adoption of socialist and revolutionary perspectives on a mass scale. They have done this, despite the fact that it is precisely these movements which have given them their birth and sustained their power, and which have been the only possible guarantee of their continued existence in class-divided, crisis-prone capitalism. The paradoxical consequence has been that, to the extent that the official representatives of reformism in general and social democratic parties in particular have been freed to implement their characteristic world views, strategies, and tactics, they have systematically undermined the basis for their own continuing existence, paving the way for their own dissolution.

For these reasons, even those most intent on calling into existence a new reformism have before them an ironic prospect. To the extent they wish to create a viable social democracy, they will have to maintain their political and organizational independence from, and indeed systematically to oppose, those who represent actually-existing social democracy. To the extent, on the other hand, they end up, as they have until now, merging themselves with the official forces of reformism, they will be disabled for carrying out what is clearly the cardinal (if enormously imposing) task facing those who wish to implement any left perspective: to rebuild the fighting capacity, organization, and left political consciousness of the working class and oppressed people. Indeed, to the degree that the proponents of a new social democracy bind themselves to already-existing reformism — its distinctive organizations, leaderships, strategies, and ideas — they will contribute, if unwittingly, to the further erosion of collective and class-based forms for pursuing workers’ interests, and thereby encourage the adoption of those individualistic and class-collaborationist forms of achieving workers’ interests which literally pave the way for the right.

https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/2508-the-paradox-of-social-democracy-the-american-case-part-one

[4]

[5]

https://angryworkersworld.wordpress.com/2016/08/29/insurrection-and-production/