India within the global cycle of class struggle 1960 to 1980

We wrote down some thoughts for a discussion meeting with comrades of wildcat (Germany) about the global uprising of 1968, looking at the wider historical background of 1968 in India.

1. ‘Independence’ was not won through a unifying national liberation movement, but handed down to the local bourgeoisie

Despite numerous local uprisings against British colonial rule and Gandhi’s salt marches and calls for non-collaboration, the colonial power was not overthrown by a popular liberation movement like in other former colonies of the global south, but rather handed down by the British administration in 1947. As well as some internal agitation, the Second World War had exhausted the Empire. ‘Independence’ was therefore not characterised by a new nation state unified by the experience of a popular anti-colonial movement, but by a central state that took over the divide-and-rule apparatus established by the British: the aftermath of ‘Independence’ saw the partition with Pakistan, language riots in the south of India against the attempt to enforce Hindi as the new national language, and there was military conflict with some of the remaining 500 local princely states, such as Hyderabad, where up to 40,000 people were killed in 1948. ‘Nation building’ did not happen against an external enemy, but against inner divisions, which meant that religious, caste-based and regional strife continued to have a major impact in the following decades. This was supported by an economic structure that was still dominated by rural and agrarian (labour) markets of local rather than national scope. While the revolution/national liberation in China 1949 entailed the curbing of the big landlords’ influence and (patriarchal) personal forms of exploitation, the social base of the Indian Congress ruling class were exactly these bigger landholders.

2. The CPI as the only organisation representing both rural and industrial workers remained integrated in the project of national democratic development

The only organisation that, at least formally, bridged the gap between small islands of industrial labour and the vast hinterland of small peasantry and rural proletariat was the Communist Party of India (CPI). The CPI didn’t take over the role of other communist parties at the time to forge a popular anti-colonial front. This was because of Stalin’s foreign policy against Nazi Germany during the Second World War which saw him order the CPI to support the British state and its army. After the war the CPI acted similarly to the PCI in Italy, in that it became a tempering, reformist force. For example, in Telangana district in 1947 poor peasants and rural labourers turned a struggle against the despotism of the local Muslim ruler into an armed uprising against bigger landlords in general. Instead of supporting this rebellion, the party leadership called for peace and a return to struggle through ‘democratic means’. As a result, the Indian state was able to suppress the rebellion. During the Indo-China war in 1962 the CPI showed their patriotic character by supporting the capitalist Motherland against the socialist aggressor. This let to a split in the party: the more China-oriented CPI (Marxist) was formed, which took state power through elections in West Bengal and Kerala in the late 1960s. Last, but not least, the CPI also supported the Indira Gandhi government in their decision impose the State of Emergency in 1975, partly because it was declared to be an ‘anti-fascist measure’, partly because the CPI saw the nationalisation of the mining and banking sector during the previous years as progressive steps. The only ‘revolutionary’ opposition to both CPI and CPI (M) during the 1960s and 1970s was monopolised by the Maoists, who largely disregarded the urban working class.

3. Peasantry and rural proletariat accounted for the vast majority in the early 1960s

In the 1960s around 80 per cent of the population still lived in rural areas, around 40 per cent survived as landless labourers. Land reforms benefited the medium-sized peasantry, who became the leading force of the Green Revolution. This saw wheat production increase by nearly 150 per cent between the mid 1960s and mid 1970s. Small peasants and artisans lost out and turned into proletarians, e.g. the share of rural labourers of Kerala’s total rural population increased from 39 per cent in 1951 to 63 per cent in 1971. The century-old caste-based village economy was transformed rapidly during the 1960s, in particular in the period of 1969 to 1974 in northern India (Punjab, Haryana): electrification, expansion of rural transport and labour markets formed the material conditions for landless labourers to question personal and caste domination. The capitalist farmers themselves had less interest in patriarchal domination and generational bonds with their labourers; their shift to market-oriented farming and higher investment levels meant that they only wanted to pay for labour once labour was seasonally necessary. Migration to the urban centres still required significant resources, while seasonal rural employment was squeezed – this led to an increase of rural agitations.

4. The global economic down-turn of the mid-1960s resonated in India

In 1951 the Nehru government enacted its first 5-year plan. While the annual growth of capital formation in the public sector was over 9 per cent during the 1950s up until the mid 1960s, it slowed down to 0.7 per cent from then on. From 1955-65, total industrial production increased at an average annual rate of 7.8 per cent. In the following decade (1965-75) the rate dropped to 3.6 per cent. On a wider level real wages and per capita income declined from the mid-1960s on. Foreign aid through the World Bank and the US (which accounted for 60 per cent of foreign aid) was first used to put pressure on the Indian state to liberalise trade and devalue the currency, but with the global crisis kicking in foreign aid also dwindled: from 1 billion USD in 1962 to 318 million USD in 1969. Inflation levels increased and the credit system dried up. In July 1969 Indira Gandhi nationalised the country’s 14 largest banks. She nationalised the mining industry a few years later – an act to centralise resources for crisis management. Unemployment levels amongst graduates increased rapidly, e.g. in the state of Bihar, one of the scenes of major unrest in the 1970s, the number of colleges increased by 284 per cent from 1951-52 to 1966-67. So while more young people were channelled into schooling, there were 14,000 unemployed graduates in 1967. The number rose to 66,000 in 1972.

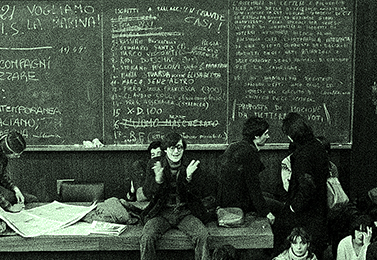

5. The Naxalbari uprising 1967 to Kolkata 1970: Maoism formed the link between impoverished rural poor and discontented urban middle-class youth

In 1967 the CPI (M) and other leftist parties formed the United Front government in the state of West Bengal, while unrest in the rural areas and amongst the urban lower middle-class youth increased. In Naxalbari, a remote rural area in the north, close to the Nepalese border, landless labourers and political militants started an armed attack in retaliation against police repression. The United Front government aided the armed forces of the central state to quell the uprising. This split the CPI (M) and marked the future of hostilities between the ruling CPI (M) and the up and coming CPI (ML). The CPI (ML) was to become the party of rural armed struggle. The Naxalbari uprising became the symbol for a generation of discontented students, who, along with their peers around the globe, idealised the Cultural Revolution taking place across the border. Thousands of students went to the countryside, supported mobilisations of the rural poor and tried to start the protracted people’s war. Armed guerilla units formed in response to the violent repression of the state and landlords and spread to neighbouring states. For example, in Bihar in 1970, there were over 600 recorded agrarian agitations, seven times more than in the previous years. Strikes were already the most significant form of struggle, which demonstrated the largely wage-dependent character of the rural poor. Following the general Maoist line the CPI (ML) largely ignored industrial workers, but had a significant following amongst the urban middle-class. The Maoists encapsulated some of the aspirations of the middle-class: patriotism against imperialism, popular power against decadent rule, real democratic development instead of the red tape of the oligarchy. In Kolkata alone 1,800 people died in 1970/71 as a result of Maoist attacks on police officers, professors, employers or activists of other political parties (mainly of the CPI (M) and Congress) and the brutal response of the state against the rebellious youth. In this sense it was the Cultural Revolution which became the reference point in 1968 in India, rather than Berkley or Paris. Nevertheless, the global movement had its influence, symbolised e.g. by the formation of the Dalit Panthers in Bombay in 1972, a political organisation of activists of the ‘untouchable’ caste that referred directly to the experience of the Black panthers in the US. Frustrated with the appeasing politics of the mainstream Dalit-Ambedkarite Republican Party of India the Dalit Party performed a similar break to the Black Panthers with the civil rights movement, though the size of their very localised organisation remained small at about 25,000 members.

6. The populist movements in Gujarat and Bihar and the railway strike in 1974: the ‘total revolution’ remained focused on parliamentary changes

It wasn’t only internal agitations causing tensions from the mid-1960s to the early 1970s. India’s ruling class engaged in a war with Pakistan in 1965 and in 1971, in the war of secession of Bangladesh from Pakistan, which caused the migration of around 9 million mainly Hindu refugees to eastern India. While initially this channeled public discontent into fear of the external enemy, the military mobilisation put further strain on state finance, in particular after the 1973 global oil shock. This aggravated the domestic situation. Over the two-year period to 1974, prices almost doubled on average, while wages remained frozen, when they were not cut. The share of crude oil and petroleum products in India’s import bill jumped from 11 per cent in 1972/3 to 26 per cent in 1974/5. Inflation increased and the black market expanded. This set off two significant popular movements in 1974 and 1975: the so called Gujarat movement, and the Bihar/JP movement, named after its official leader Jayaprakash Narayan. The social base of these mass movements were students and white-collar workers and their trade unions. The focus was the corruption of the Congress Party, which had been in power since 1947, as well as inflation and hoarding by black marketeers. The movement sparked university occupations, the opening of warehouses suspected to contain hoarded goods, violent clashes with the police, as well as road and railway blockades. In Gujarat the social unrest permeated the repressive organs of the state itself. During the ‘Lucknow Mutiny’ members of the para-military Provincial Armed Constabulary rebelled against their inadequate pay and miserable service conditions by joining the ranks of student protesters they were meant to repress. This fraternisation had limits; in January 1974 in Gujarat 100 people were killed by state forces, around 3,000 were injured, and 8,000 arrested. The Bihar movement was triggered by these events and followed similar patterns, though remained more under the control of the political leader, JP Narayan, who demanded certain administrative reforms and the revival of small-scale industries under the name of ‘total revolution’. While urban Bihar was shaken by demonstrations and a strike of 400 public sector unions, the railway unions called for an India-wide strike in May 1974. The strike involved 1.7 million workers, mainly demanding higher wages and shorter working hours. It threatened to spread to the affected major industrial centres, such as steel and coal, who relied on rail transport. The strike call was given for the 8th of April 1974. Indira Gandhi responded to this call by declaring the strike illegal under the provisions of the “Defence of India Rules”, inherited from the colonial days. Strike activists were arrested under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act. Despite this, the strike still went ahead and lasted from 8th of May till 27th of May. During this period over 50,000 workers were sent to jail and 15,000 people lost their jobs. This repression was clearly a precursor of the repression of the state of emergency a year later.

7. The State of Emergency 1975 to 1977: a phase of developmental dictatorship

The imposition of the state of emergency in 1975 was a measure to cope with the social unrest aggravated by the 1973 crisis. It was also another sign of India’s political and economic integration within the world system, following similar shifts to draconian policies in other parts of the world, from Chile to Poland. Declared as an ‘anti-fascist measure’ against the right-wing opposition, such as the Hindu-nationalist RSS, and supported by the CPI, the state of emergency largely targeted the urban and rural proletariat. During the twenty months it lasted over 200,000 opponents were arrested, the urban areas witnessed an increase in slum demolitions, e.g. in Delhi around 71,000 poor people were expelled from city centre, often with brute force (Turkman Gate massacre). In both urban and rural areas proletarians were targeted by sterilisation programs: around 11 million people (mainly male proletarians) were sterilised during the state of emergency. Many of them were rounded up by police and forced to comply. While these are more well-known facts the impact of the state of emergency on industrial workers is less well documented, e.g. many workers in Faridabad reported how management used the strike ban to enforce restructuring and intensification of work. Some figures for the scale of restructuring and capitalist offensive: within the first months of the Emergency 20,000 workers in multinational companies were laid off; in the first year of the Emergency a total of about 700,000 workers were laid off. During the Emergency lock-outs accounted for nearly 95 per cent of (wo)man days ‘lost’ [sic!]. During the first half of 1975, 17 million (wo)man days were ‘lost’ to strike, during the second half only 2 to 4 million. Strikes were declared illegal, a general wage freeze imposed and annual statutory bonus payment cut by 50 per cent. There was a 10 per cent increase in industrial output in 1976 compared to 1975, while during the same period unemployment increased by 28 per cent. The state of emergency turned into a social pressure cooker. The social anger due to inflation and unemployment which existed before was aggravated by authoritarian rule that extended to the countryside, the urban working slums and the factories. At the same time the two main forces of ‘working class institutionalisation’, the Congress and the CPI, had largely discredited themselves amongst the working class. During the sudden upsurge of working class struggles in 1977 to 1979 the Congress trade union (INTUC) and the CPI trade union (AITUC) were completely pushed aside.

8. After the State of Emergency 1977 to 1979: glimpses of workers’ autonomy

The old labour movement, based in, for example, the jute mills in Kolkata, textile mills in Bombay, steel plants in Jamshedpur or the coal mines in Dhanbad was largely tied to the CPI and often more segregated in caste terms. From the 1960s onwards new industrial centres emerged, one of them in Faridabad in Haryana, but also Indore, Kanpur, Pune, Bhopal… Here workers were more mixed, as the changes in the rural labour market and peasantry brought proletarians of various religious and caste backgrounds into the city. The industry was of a more modern type and often linked to international investment. There were violent strikes before the 1970s, such as at the East India Cotton Mill in Faridabad in 1969 or at Goodyear in 1973, but the real explosion only happened after the lifting of the state of emergency in 1977. For two years industrial areas like Faridabad were pretty much out of control, with managers being beaten up during nightshifts, managers’ canteens being re-appropriated by Dalit factory cleaners and frequent wildcat strikes. The newly elected Janata government, which praised itself as the defender of democracy against the cronies of the Congress quickly had to resort to very draconian measures to quell the unrest, e.g. at the Swadeshi Cotton Mill in Kanpur in 1977 or in Faridabad in 1979. On 26th of October 1977, after wages had not been paid for several weeks most of the 8,000 workers at Swadeshi Cotton surrounded the factory and held the main managers inside. The trade unions were not involved, leaders of all main trade unions were beaten up. Workers placed gas cylinders and acid bottles on the factory roof and threatened to blow things up. The workers’ wages were paid after 54 hours of ‘siege’. The various ongoing conflicts reached a climax on 6th of December when around 1,000 workers again surrounded the factory. Trouble with armed security guards started, two managers died in the confrontation. The police intervened by shooting at the mass of workers confined in the premises. Official numbers stated 11 dead workers, workers said that over 100 people died. A similar situation happened in Faridabad after a wave of strikes in 1979. In an attempt to align the general discontent behind their ‘leadership’ the main trade unions plus neo-Maoists called for a Faridabad-wide general strike on 17th of October 1979. A huge crowd gathered near Neelam Chowk, under a major fly-over. After a short provocation police started firing from strategic positions on both sides of the fly-over. While official figures said that 17 people were killed, unofficial numbers ranged between 100 and 150 dead people. Some workers were shot dead in front of their homes several miles away from the scene, having been followed by the cops. The violent repression at the end of the 1970s opened the way for the restructuring of the 1980s: mass dismissals, introduction of amongst others, table-print machines and automatic weaving looms, which slowly finished off the workers’ offensive. The great Bombay textile mill strike of 1982 involving 200,000 to 300,000 workers can be equated with the FIAT blow of 1980 or the miners strike in Britain in 1984: a politically concerted attack on the remaining large bastions of workers’ power. The economy in India dragged itself through the rest of the 1980s, only to collapse under the foreign debt burden like many other major global economies in 1990/91.

9. Conclusion

The only veritably organised and self-proclaimed revolutionaries in India in the 1960s and 1970s were the Maoists. However, while they claimed that India was a half-feudal and half-capitalist society that required a democratic revolution in order to overcome its backwardness, in hindsight we can see that it was the class struggle under capitalist conditions that was the actual revolutionary force. Society in India underwent a leap in development. In the 1960s there were around 400 to 450 million people living in India; today there are over 1.3 billion. Life expectancy back then was around 45 years, today it is close to 70. While still a predominantly rural society, agriculture accounts for only around 15 per cent of GDP – it was still above 30 per cent only three decades ago. Like their peers in China, nowadays young workers know more about the world thanks to mobile phones and the internet. Companies like Tata run car factories in England and steel plants around the globe. In the late 1960s and early 1970s proletarians had just started to establish a regular migratory connection between the rural areas and the industrial centres themselves – before that point a truly revolutionary upheaval encompassing both village and city would have depended on formal organisations which have traditionally been in the hands of the middle and upper class. In terms of a potential for a wider working class social transformation, perhaps 1968 was just a little early.

AngryWorkers, May 2018