We translated this article as a background text for our contribution to the party building debate. For us the situation in Italy in the 1970s is a suitable historical context in order to discuss the role of political organisations and their relation to class struggle. The following text is limited to the situation in Milan, which is a weakness, but it demonstrates the complexity of the movement at the time. For a deeper involvement with the period we suggest reading our summaries on the political committee at Magneti Marelli and on the political organisation Senza Tregua.

The historical account clearly shows the problematic role that the ‘mass party’ PCI played during these tumultuous times and the limitations of attempts to create an electoral alternative to the left. It also shows the insufficiency of a ‘network of autonomous initiatives’ when confronted with a coordinated attack of restructuring, launched by the state and its various institutions.

For us the organisational efforts of the Communist Committees for Workers’ Power expressed the most advanced point at the time, as they were based in significant industries and developed a political practice that went beyond the factory walls. With Senza Tragua they developed a political platform that discussed revolutionary and ‘military’ strategy in close relation to the actual struggles. It will be a future task to discuss why the effort to re-create a wider political organisation failed and why necessary armed actions degenerated into adventurism.

THE POST-WAR PERIOD

Milan and its surrounding area have always been one of the hubs of the Italian revolutionary movement, not so much for their theoretical developments, but because things happen here, often well ahead of the rest of Italy and with greater intensity. In particular, it is the working class that has been at the forefront of new behaviours. It was from the factories and working-class neighbourhoods that, on the 25th of April 1945, the liberation of the city occupied by the Nazi-Fascists began. Even before that in 1943, the workers at Alfa Romeo had launched strikes and the first anti-Fascist mobilisations, which were harshly punished, often with deportation to German concentration camps. This protagonism was therefore characterised by a strong anti-fascist and socialist political consciousness, but also by values centred on the ideology of work and on ‘considering themselves the healthy and productive part of the nation as opposed to the bourgeoisie, which was seen as corrupt, incapable and parasitic’.

In the immediate post-war period, Milan became a centre of the political sector of the so-called ‘betrayed Resistance’, which between May 1945 and February 1949 gave rise to the Volante Rossa (Red Flying Squad) in Milan and its surroundings. This was an armed group of former partisans who intended to continue the armed struggle to move from the liberation from Nazi-Fascism to a socialist revolution. This group was openly rejected by the Italian Communist Party (PCI), which had already decided to form a constitutional pact with the industrialists to guarantee Italy’s economic and productive recovery within the new party system that had emerged from the Resistance and in accordance with the spheres of influence established by the US and the USSR.

However, Milanese workers still felt they were protagonists: locked in within the factories, proud of their professional skills, confident in the political leadership of the PCI, they considered themselves the custodians of a historic task to be accomplished through the world of work: the continuous development of productive forces and the implementation of the Constitution born out of the Resistance.

The development model chosen by Italian capitalism involved extremely high productivity guaranteed by the ideology of work and very low wages ensured by the total inefficiency of the trade unions. At the end of the 1950s, this model allowed enormous profits for national monopoly capital but it also required a major restructuring of production in order to compete on international markets, in order to increase domestic consumption and its ability to control the new generations and the working class itself. This objective involved the massive introduction of the assembly line using unskilled labour, thus undermining the figure of the skilled worker, who was highly politicised unlike the ‘new’ worker (the mass worker), who had no tradition of resistance or socialism. The working class saw as a tactic what for the PCI was actually a strategy, while capitalism carried out its plans to rebuild and reorganise its power in the factories. The instinctive behaviour of the workers was one of rejection: rejection of piecework, rejection of ever tighter deadlines, rejection of hierarchy and of the bosses’ discipline at work. The behaviour of the political and trade union organisations, on the other hand, was one of adaptation to the rules of capital.

THE SIXTIES

The situation began to change in July 1960 with the anti-fascist revolt in Genoa. It marked a break with the reformist leadership, which did not recognise the young people (the ‘striped shirts’), who wanted to prevent the neo-fascist congress in the city, as their own.

In 1962, during a demonstration in Milan against the US policy towards Cuba, Giovanni Ardizzone was killed when he was run over by a police van. Once again, the PCI blamed the demonstrators for what had happened. However, the split between reformism and the new working class reached its peak with the clashes in Piazza Statuto in Turin in July 1962.

Between September 1960 and March 1961, the ‘historic’ struggle of the Milanese electrical mechanics took place, which was characterised by a fierce clash with the employers and the police, with strikes, pickets, street demonstrations and police charges. It highlighted the workers’ refusal to integrate despite capital’s attempts at a policy of high wages and “prosperity”. This was the first spark that would lead to the hot autumn of 1969. It was the first sign that the Italian working class was not integrated, that it could win against employers who traded the ‘economic miracle’ for a regime of exploitation that consisted of increased work rates and piecework, while wages remained stagnant. It was a struggle that anticipated many of the workers’ demands of the following years: reduction in working hours, wage increases, equal pay for men and women, sick pay and accident compensation. The head of the metalworkers‘ industrialists, Ferdinando Borletti, wrote that “the ongoing struggles are setting goals that touch on the very structure of the employment relationship, in that they tend to remove the responsibility of the control over the company from the employer”. In other words, the question of workers’ power was put on the table.

However, the desire for change was not limited to the working class. The whole of society was sending out strong signals of discontent, and the gap between institutions and citizens was widening. The crisis affected not only the major forms of representation (political parties, trade unions, associations) but also most of the established models of daily life. The institutional response to this change was the centre-left government, which immediately appears to serve capitalist development rather than expressing a political will for renewal.

The state responds to the new ferment coming from workers and young people with harsh repression. The reform of secondary education, apparently egalitarian, shows that little has changed compared to before; on the contrary, it is even more rigid and selective. In the mid-1960s, a student political consciousness began to form. There were still no radical forms of protest, but the signs of discontent were widespread and revealed the rift between young people and the institutions. This is evidenced by the story of the student newspaper La Zanzara at the Parini high school in Milan, which in February 1966 published a survey on what female students thought about sexuality and premarital relationships, denouncing ‘a serious pedagogical deficiency in society, and in particular in schools’ towards young people and their freedom. The survey was opposed by Gioventù Studentesca, a group led by Don Luigi Giussani, the future founder of Comunione e Liberazione, and the ‘scandal’ made the front pages of the newspapers. The judiciary intervened and immediately brought the three student editors of Parini, the headmaster Daniele Mattalia and the owner of the printing house to trial. Among the defence lawyers were Sergio Spazzali and Giuliano Spazzali, who were prominent figures in the defence of communist militants and workers throughout the 1970s.

Thanks to the influence of figures such as Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, a counterculture also emerged in Italy. The first forms of the Italian beat movement were recorded in Milan in 1965, when a group of ‘capelloni’ (long-haired hippies) rented a shop on Viale Montenero and turned it into a meeting place. In November 1966, also in Milan, ‘Mondo Beat’ was published, the first Italian underground newspaper. It quickly became the link and communication tool for various groups operating in Italy, including Onda Verde, undoubtedly the most important in terms of cultural depth and planning, founded by Andrea Valcarenghi, who later became the promoter of ‘Re Nudo’ and one of the leading figures of Italian counterculture. The beat movement was harshly repressed, but this did not prevent the practice of liberated spaces (communes, use of squares and streets). In Milan, an attempt was made to create an open-air commune by renting a piece of land in Via Ripamonti (in summer 1967). The Corriere della Sera newspaper did not hesitate to call it Barbonia City, alluding to ‘sacrilegious blood weddings’, drugs, rape and orgies, and describing it as a hotbed of infectious diseases and a refuge for runaway minors. The police proceeded to clear the area violently.

Meanwhile, the intensity of the workers’ struggles grew throughout Italy, with the PCI remaining faithful to its “policy of planning”, i.e. a policy that allowed for the planning of economic, productive and political development. The PCI only demanded the ‘democratic’ participation of communists and trade unions in the development of these capitalist development strategies – the party proclaimed the myth of the working class becoming the state. Most workers remained loyal to the party and the trade unions, partly due to a lack of political alternatives, but it was clear that the tendency among workers was to break contractual rules and separate wages from productivity. The forms of struggle of the mass worker were the ‘wildcat’ or ‘whistle’ strike, the ‘checkerboard’ and ‘hiccup’ strikes, which coordinated the strike strategically across different departments. These forms were all outside the trade union tradition and corresponded to the slow formation of ‘autonomous class behaviour’.

This climate of change produced magazines such as Quaderni Piacentini, Quaderni Rossi and Classe Operaia, which introduced critical and radical points of view in the political and cultural fields, and in particular gave rise to Operaism [1]. In the early years of its existence, the ‘Operaista’ intervention in the Milan area was considered ineffective, but there is no doubt that many of the efforts documented in our archive can be included in the area of workers’ autonomy (with a lowercase “a”) and the rejection of work. In Milan, the intervention was systematic, but produced few organisational results. Sergio Bologna mentions “a spontaneous strike with a march to the prefecture of the Innocenti di Lambrate in May 1965’. I remember the departmental struggles at Siemens in Piazzale Lotto, at Autobianchi in Desio, at Farmitalia and at Alfa Portello. We had comrades in Como, Varese, Pavia, Monza and Cremona who were involved in other large factories in Lombardy. But we didn’t know anyone at Pirelli. What was the result of this underground work? A knowledge of the factory in all its aspects that no one else in Italy had at the time, not even the people of Turin, crushed by the monoculture of the car industry, nor the Venetians or the Genoese. The industrial landscape of the Milan area was more varied, more sensitive to innovation, more open to foreign industry”. With the end of the publication of Classe Operaia, however, this intervention in the factory finished.

There are the episodes of this period that are worth remembering. In 1966, on the occasion of the inauguration of the Milan Trade Fair, thousands of workers went on strike and went to the fair to protest against the then President of the Republic, Giuseppe Saragat; the trade unions tried to prevent the demonstration, and a real guerrilla war broke out between Alfa Romeo workers and the police, including an exchange of ‘prisoners’.

During the 1966 contract negotiations at Siemens in Milan, the first democratic workers’ organisation was formed, a factory council before its time. The council took the form of a strike committee composed of departmental delegates. The committee was short-lived due to fierce union sabotage, but the message was clear: workers were beginning to consider new forms of representation. In February 1968, again at Siemens, the first strike by office workers and technicians took place. From that moment on, worker unrest and initiatives resumed (with the establishment of so-called study groups) in all factories. It was the first time in the post-war period that sections of the workforce – the white-collar workers – who were traditionally used as an anti-worker force and social vehicle for the bosses’ regime in the factory, broke their bonds of dependence and chose the path of class solidarity.

These significant experiences of worker dissent were accompanied by the first forms of intervention by the nascent revolutionary left (made up mainly of students). Their egalitarian and anti-productive themes influenced large sections of the worker vanguard and trade union cadres.

THE TWO RED YEARS

In 1968, Milan was at the forefront of the protests, with various occupations, for example, the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart was occupied for the first time on the 5th of December 1967 and there were related clashes in Largo Gemelli on the 25th of March. There was the siege of the Corriere della Sera newspaper (8th of June) and the occupation of the former Commercio hotel in Piazza Fontana (28th of November), ‘a dagger in the heart of the capitalist city’, and the anti-consumerist protest at the opening night of La Scala (7th of December).

The struggles in Milanese factories in 1967–68 expressed a strong autonomy of workers’ behaviour with respect to the reformist politics of the PCI and the trade unions, which were now incapable of governing the growing conflict.

The struggle against trade union collaborationism was divided between those who remained within the trade union structures to change them from the inside and those who considered them unreformable and set up autonomous workers’ organisations capable of developing mass action on a class basis. In the spring of 1968, after the grandiose and victorious strikes against wage restrictions and for pension reform, the first Comitati unitari di base (CUB, Unitary Base Committees) were formed in Milan.

The best known and most important CUB was formed at Pirelli in Milan and presented itself without political labels but as a nucleus for organising the struggle for a company collective contract. These new forms of organisation encouraged all the groups to the left of the PCI to intervene outside the gates of the Bicocca factory (PCd’I, Avanguardia Operaia, but also Classe Operaia and later on Potere Operaio): the CUB seemed impervious to these external interventions, while the trade union sections of the factory exerted heavy pressure to call back the dissident activists.

The basis of the CUB Pirelli’s action was the material condition of the workers in the face of capitalist exploitation. Therefore its political line had to adhere to the condition of the workers in the factory, verifying the content and instruments of struggle through action, thus developing the level of workers’ consciousness. The CUB was aware that in the clash with the capitalist plan, the working class has reached a maturity that was later on verified during the Hot Autumn of 1969. At the centre of the struggle that the CUB supported was the question of workers’ power, and the attack on the bosses was comprehensive. The contradictions of the capitalist plan emerged only when workers understood that all their economic needs were part of a more general regime of exploitation and that they could find satisfaction through a general struggle to seize power.

The CUB assumed that organising solely for a struggle for demands was doomed to failure, since only political content could generate a general rejection of the economic conditions. Hence there was a need to identify the various workers’ articulations and the economic needs that were capable of taking on concrete political meaning. According to the CUB, workers should not simply fight for the regulation of piecework or the improvement of the working environment, but through the actual enforcement (e.g. through the self-reduction of the pace of work) workers can challenge the decision-making power of the bosses.

The CUB intended to overcome the phase in which there is a division between the economic moment of the struggle, managed by the trade unions, and the political moment, managed by the reformist parties. Only the union of economic and political struggle can bring capitalist society into crisis. The CUB, therefore, became an attempt to restore to the working class its role as the subject of both economic and political struggle. The CUB did not present itself as an alternative structure to the trade unions, but questioned their objective role within the capitalist system, whose specific task is to contain workers’ struggles. The CUB therefore stood alongside the trade unions in factory intervention, but pursued a different approach, which was often attacked and rejected by the trade unions, but sometimes also recuperated.

The CUB did not accuse the trade unions of being ‘traitors to the working class’, but pointed out their inherent limitations, which could only be overcome through the autonomous political organisation of the struggles. These characteristics of the CUB contained everything that is meant by workers’ autonomy. The experience of the CUB Pirelli foreshadowed the movements and grassroots trade unions of the 1970s, not so much as an organisational formula but as a strategy. This strategy centered around the rejection of work, which was expressed in the struggle against and abolition of piece rate and bonus systems and for equal pay increases instead of the employers’ promotion system. The strategy also expressed itself in the fact that it found goals of struggle that could be achieved without going through negotiation.

The workers’ ability to create a different system of work organisation and a different atmosphere in the factory without going through trade union mediation was reaffirmed. According to Sergio Bologna, it was for the first time since the days of the Resistance post-WWII that such complex forms of self-reduction of production had been achieved by workers. These were forms that required extraordinary participation and unity on the part of all workers, including technicians.

During the same period, some worker-militants and a group of workers at Snam Progetti in San Donato Milanese started collaborating and formed the Permanent Assembly of Snam. Here, the struggle broke out in mid-October 1968 with the occupation of the offices and continued until mid-November, when students occupied the Milan Polytechnic.

The question of ‘technicians’ was raised forcefully by militants and worker-intellectuals. A large national conference of technical and scientific faculties in struggle was held in Milan in November 1968. This conference produced important analyses of the technological restructuring underway and the tasks assigned to technicians by neo-capitalism, as well as the training of technicians by schools and universities.

In his speech, Franco Piperno of Potere Operaio underlined the revolutionary intelligence and technical-scientific competence of technicians, which made them important for the ongoing class struggle. On the 15th of February 1969, the first national demonstration of technicians and employees of large industries took place in Milan.

Milanese workers were at the forefront of the workers’ struggles throughout 1969, in a crescendo that culminated in the “Hot Autumn”. An impressive procession of 100,000 workers marched on the Assolombarda building and on the 19th of November, a highly successful national strike for housing took place, which paralysed the cities with demonstrations everywhere. In Milan, tension increased to such an extent that while the secretary of the CISL trade union, Bruno Storti, was finishing a speech at the Teatro Lirico, riot police vans loaded a crowd of workers and students at the same time in the adjacent Via Larga. The clashes were brief but extremely violent. The police officer Antonio Annarumma was killed. The reaction of the institutions and the mass media was furious, linking the event to the tension of the factory struggles and writing of chaos and the danger of subversion. The next stage of the strategy of tension was prepared, leading to the fascist Piazza Fontana bombings in Milan on the 12th of December, a ‘state massacre’. The bombing was blamed on anarchists and Giuseppe Pinelli was killed by the police after his arrest.

The bombing at Piazza Fontana had public precursors, e.g. the bombs that exploded on the 25th of April 1969 at the Fiat pavilion of the Trade Fair, causing several serious injuries, and at the currency exchange office of the central station. Not to mention that on the 12th of December, a second unexploded bomb was found in the central Milan headquarters of the Banca Commerciale Italiana.

From the 19th of December 1969, a signed leaflet could be read on the walls of Milan. It was entitled ‘Il Reichstag brucia?’ (Is the Reichstag burning?) by the friends of the INTERNAZIONALE (Situationist) and suggested a correct interpretation of what had happened: ‘Faced with the rise of the revolutionary movement, despite the methodical efforts of the trade unions and the bureaucrats of the old and new “left” to contain and integrate it, it has become fatal for those in power to use the old playbook of law and order. This time they play the false card of terrorism in an attempt to avert a situation that would force them to reveal their hand in the face of the clarity of the revolution’.

THE EARLY 1970s

Out of a desire to shed light on what was happening, in May 1970, the ‘Bollettino di controinformazione democratica’ (Democratic Counter-Information Bulletin) and the National Committee for the Struggle against the State Massacre (‘Strage di Stato’) were founded. The book La Strage di Stato (The State Massacre) was published, which dealt with the collective battle in defence of the arrested comrades. It proposed militant anti-fascism and the construction of structures to defend the movement’s spaces of action, such as the Soccorso Rosso (SR), which was formed by lawyers, intellectuals, artists (above all Franca Rame and Dario Fo), revolutionary militants, students and workers. The SR played a leading role in the first half of the 1970s when it came to legal defence and support for prison struggles.

The lawyers and journalists who gave life to these experiences developed a line of thinking that led to a rejection of the role and profession of the technician, a process that had already begun with the Quaderni Rossi. Rejecting the role (of the journalist or the lawyer) meant being aware that ‘capitalist knowledge’ was ‘science hostile to the class’ and it meant revealing the roots of domination and exploitation: counter-information was born.

The massacre at Piazza Fontana also marked the ‘end of innocence’ for the movement that had characterised the ‘red biennium’ of 1968–69. The movement was eroded and party projects survived: extra-parliamentary groups (Marxist-Leninists, workerists, Trotskyists) emerged which would characterise the Italian revolutionary scene in the first half of the 1970s. In Milan Avanguardia Operaia, the Unione dei Comunisti (m-l) and the Movimento Studentesco were formed as the main new party projects. Whoever intended to intervene in the Milanese movement would have to contend politically and ‘militarily’ with these groups. These groups revived the Third Internationalist tradition and defeated the more ‘creative’ theoretical and practical efforts. In particular, they marginalised the workerist and anarchist milieus, the Situationists and the most intransigent Marxist-Leninist groups. The rift in the movement between the political wing and the countercultural and social-creative wing (which was strong and very active in Milan, think of ‘Re Nudo’ and the Situationists) was deep. Only the group Gruppo Gramsci made generous but unsuccessful attempts to heal the rift during the 1976 Festival del Parco Lambro.

Among the groups that emerged in Milan were the Collettivo Politico Metropolitano (CPM) and later Sinistra Proletaria (Proletarian Left), which identified the political limits of the factory struggle and chose to go beyond workers’ autonomy, focusing entirely on militancy and the organisation of cadres. The CPM was the organisational result of the debate that swept through the Milanese CUB area in 1968–69 and was created to extend its action from the factory to the social sphere, to overcome the contradictions inherent in the separation between factory struggles and social and student struggles. Particularly in Milan, the CPM quickly became a mass organisation present in dozens of factories and schools. It was viewed with sympathy and interest above all by the militants of Potere Operaio, who, despite their differences in approach, saw the CPM as a concrete example of an organisation of workers’ autonomy. During 1970, the CPM published Sinistra proletaria, a publication for information and coordination between struggles, which was replaced by Nuova resistenza’ (New Resistance) after two issues. In Milan, the Collective led and supported (as Sinistra Proletaria and in alliance with Potere Operaio and Lotta Continua) many factory struggles, some large housing occupations in the Gallaratese district and in Via Mac Mahon, and launched the transport struggle campaign Prendiamoci i trasporti (Let’s take transport), which tried to enforce free public transport. Also important was its constant intervention among worker-students (Movimento Lavoratori Studenti, Istituto Tecnico Feltrinelli) and technical workers (CUB Pirelli, Gruppo di Studio Sit Siemens, Gruppo di Studio IBM).

In 1970, the Brigate Rosse (BR) (Red Brigades) were formed from the CPM and carried out their first armed actions inside factories, particularly at Sit-Siemens and Pirelli in Milan. Previously, the BR had held flying pickets in the working-class neighbourhood of Lorenteggio, also in Milan, and distributed leaflets in front of Sit-Siemens.

At the same time, the Gruppi d’Azione Partigiana (GAP) (Partisan Action Groups) were founded by the Milanese publisher Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, who believed that a coup d’état was imminent in Italy and acted with reference to the partisan resistance.

In November 1970, Lotta Continua launched the ‘Prendiamoci la città’ (Let’s take the city) programme, which shifted the focus from the factory, which supposedly was no longer capable of driving the movement, to the social arena.

In 1971, a faction of the Student Movement, led by Popi Saracino, split off and formed Gruppo Gramsci. The Gramsci militants established contacts with the rest of the extra-parliamentary left, which were rejected by the Student Movement, which was entrenched in the State University. Gruppo Gramsci published a monthly theoretical journal, ‘Rassegna comunista’ (Communist review).

In 1971, Primo Moroni opened the Calusca bookshop in Corso di Porta Ticinese 106, which would become a veritable crossroads of countless paths of theoretical elaboration, counter-information, countercultures and non-conformist social practices.

In June 1971, the first national conference of feminist groups was held in Milan, attended by Demau (Demistificazione dell’autoritarismo patriarcale, Demystification of Patriarchal Authoritarianism, which was founded in Milan in the late 1960s) and Rivolta Femminile (Women’s Revolt).

In September 1971, new militants from Potere Operaio (Antonio Negri, Emilio Vesce, Giovanni Giovannelli, Gloria Pescarolo, Gianni Mainardi, Gianfranco Pancino and Oreste Scalzone) arrived in Milan to carry out their political activities, joining Sergio Bologna, Giairo Daghini and Bruno Bezza. This showed how important the organisation viewed the political intervention in Milan. The Milanese intervention focused on Alfa Romeo, Pirelli, Eni, Snia, Farmitalia, Telettra, secondary schools and universities, particularly the Faculty of Architecture, where Alberto Magnaghi developed a technical and political discourse on the relationship between architecture and territory. Offices were opened in Via Maroncelli and, for a short time, in Varedo (to attempt an intervention at Snia).

The long season of protests at pop and rock concerts began, stimulated and sometimes organised by ‘Re Nudo’ and Stampa Alternativa. The protagonists were young proletarians who wanted to ‘take back their music’ and protest against the capitalist exploitation of their needs, demanding their right to attend concerts free of charge. The protest at the Led Zeppelin concert at the Vigorelli velodrome on the 5th of July 1971 was historic.

The great counter-information campaign and the mass campaigns Valpreda libero! (Free Valpreda!) and La strage è di stato (The massacre was state-sponsored) brought down the attempt by the secret services to frame anarchists for the Piazza Fontana massacre: militant counter-information was born. In February 1972, the trial for the massacre began and it turned into a heavy indictment of ‘state plots’. On this occasion, on the 11th of March, one of the most violent street demonstrations in living memory took place in Milan, with the city ‘held’ for hours by comrades throwing Molotov cocktails, particularly at the Corriere della Sera newspaper.

On the 3rd of March, the Siemens Macchiarini engineer was kidnapped by the Red Brigades in Milan and subjected to a ‘political trial’ lasting about twenty minutes before being released. This first political kidnapping was viewed with sympathy by the workers’ vanguard and some extra-parliamentary organisations such as Potere Operaio and Lotta Continua.

On the 15th of March 1972, the body of Giangiacomo Feltrinelli was found under a pylon in Segrate (Milan), with several live explosives next to him. Feltrinelli’s death and the speculation that accompanied it marked a crucial episode in the debate of those years. The episode ended the collaboration that had been created between the revolutionary movement and ‘democratic’ areas composed of prominent figures in journalism, the judiciary and reformist left-wing intellectuals: the paranoia of the ‘internal enemy’ was born. In the initial phase, the ‘democrats’ and part of the extra-parliamentary groups interpreted Feltrinelli’s death as yet another episode of the ‘strategy of tension’, as a ‘state murder’, with no doubt that it was a provocation. However, Potere Operaio broke with the conspiracy theories and, in an issue of its newspaper, revealed Feltrinelli’s militancy in the GAP under the nom de guerre ‘Comandante Osvaldo’. This revelation reignited the debate on clandestine groups and created a split within the revolutionary front: Lotta Continua sided with Potere Operaio, while Avanguardia Operaia and the ‘democratic’ factions left the National Committee for the Struggle Against State Terror and accused Potere Operaio and Lotta Continua of proposing a crazy analysis of the Italian situation and of the movement’s tasks, which brought Potere Operaio and Lotta Continua closer to the armed groups GAP and the BR.

On the 17th of May, police commissioner Luigi Calabresi, who was involved in the investigation into the death of the anarchist Pinelli, was killed in Milan. After a long series of trials, the judiciary attributed the murder to militants of Lotta Continua.

THE BIRTH OF WORKERS’ AUTONOMY

In September 1973, the magazine Primo Maggio was founded by Sergio Bologna, Lapo Berti, and Bruno Cartosio. In 1974, the magazine Critica del diritto began publication, with contributions from labour magistrates such as Romano Canosa and Ezio Siniscalchi, as well as Antonio Negri.

Controinformazione was founded, with Emilio Vesce as editor-in-chief for the first few issues. The initial editorial staff included Franco Tommei, one of the leaders of the city’s autonomy movement. This collaboration cost him his arrest after the police discovered the Red Brigades’ base in Robbiano di Mediglia, where documents were found linking the newspaper and part of the Milanese autonomy movement to the Red Brigades themselves.

In the anarchist milieu, the Centro comunista di ricerche sull’autonomia proletaria (Ccrap) (Communist Centre for Research on Proletarian Autonomy) published ‘Proletari autonomi’ (later ‘Collegamenti Wobbly’), a magazine representing the libertarian experience in the Milanese autonomy movement, with Cosimo Scarinzi and Roberto Brioschi among its promoters.

Also from the libertarian milieu were the ‘comontisti’ (Riccardo D’Este, Dada Fusco, Roberto Vinosa, Paolo Ranieri), who published Comontismo and were involved in various squats and collectives. Among them was Giorgio Cesarano, author of numerous fundamental texts and, together with Max Capa, one of the driving forces behind the magazine Puzz, an underground comic newspaper. They were also involved in a collective in Quarto Oggiaro that expressed extremely radical positions within the Milanese autonomous movement.

1973 was a crucial year, particularly marked by the occupation of the Fiat Mirafiori factory by workers in struggle, the fascist coup in Chile and the historic compromise proposed by Enrico Berlinguer, secretary of the Italian Communist Party. While everyone within the revolutionary movement agreed that the strength of workers’ autonomy had reached a limit within the factory walls, there was division over the strategy regarding the realisation that reformism had not been dealt a decisive blow.

The occupation of Mirafiori and Pinochet’s coup provoked a series of reflections on the part of the PCI (which drew up the historic compromise) and the revolutionary groups in crisis. Avanguardia Operaia, Movimento Studentesco and PDUP definitively chose the institutional path; Lotta Continua began a process that led it to endorse the PCI in the 1975 local elections and then to join the Democrazia Proletaria electoral cartel. The position of Potere Operaio and a section of dissidents within Lotta Continua was different. They drew from the Chilean coup a conclusion opposite to that of the PCI: the mistake of Salvador Allende, president of Chile, was not his failure to ally himself with the Christian Democrats, but rather his failure to arm the people against the attacks of the right. The occupation of the Mirafiori factory demonstrated the workers‘ ability to resist attacks by the bosses and their willingness to fight back at the level of power. Workers’ autonomy as it had been understood until then was outdated: workers’ power had to be expressed not only in the factories but also outside them, becoming a force to be reckoned with.

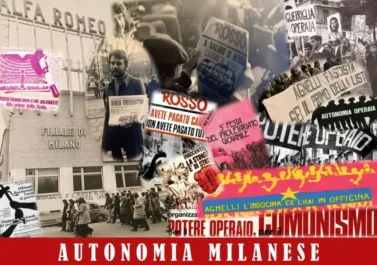

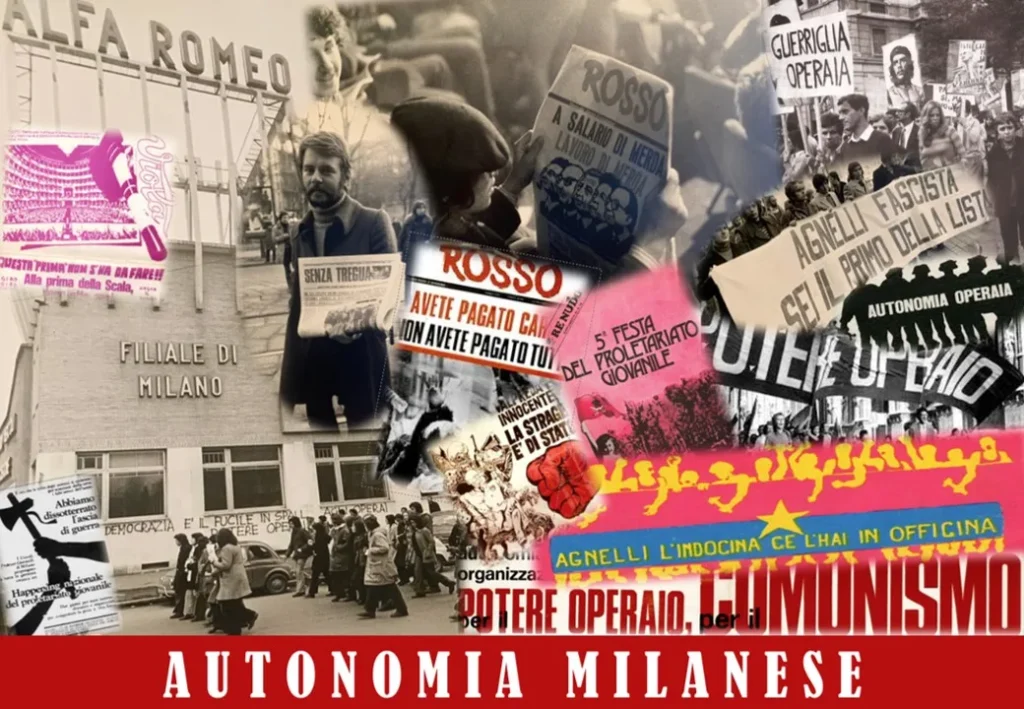

At the heart of the nascent Autonomia Operaia were the workers’ assemblies, particularly those at Sit Siemens, Alfa Romeo and Pirelli, but also those at Motta and Alemagna. In the Milanese laboratory, the figure of the precarious worker emerged, the worker on fixed-term contracts, seasonal work that lasted all year round, home-based and undeclared work, the worker who had no means of opposition. This opened up new horizons for political intervention: the feminist movement exploded and a new class consciousness spread, placing creativity and needs at the centre of its practice.

This ferment led to various developments and organisational attempts. A discussion forum was formed around the most important autonomous workers‘ organisations (Assemblea autonoma Pirelli, Assemblea autonoma Alfa Romeo, Comitato di lotta Sit-Siemens) with the aim of establishing the area of Workers’ Autonomy (‘Giornale degli organismi autonomi’). The general crisis of extra-parliamentary groups also affected Gruppo Gramsci (‘Rassegna comunista’ and ‘Rosso’), which was present in Milan and Varese among teachers, intellectuals and workers in the northern area (Face Standard, IRE Ignis). For some time Gruppo Gramsci had been criticising the classic forms of organised political groups and Leninist vanguardism, seeking instead forms of grassroots organisation that prefigured a path of liberated social relations (Collettivi politici operai (CPO), Collettivi politici studenteschi (CPS)).

A significant number of those who left Potere Operaio after the Rosolina conference (Ro) (May-June 1973, a few months after the workers’ occupation of FIAT Mirafiori) decided to join the Gruppo Gramsci and dissolve within the nascent Autonomia Operaia (‘Rosso’). In Milan, a metropolitan intervention structure was set up, involving workers from Sit-Siemens, Alfa Romeo and, later, many other factories in the northern belt. It was within this dynamic that dozens of collectives were formed in neighbourhoods, schools and factories throughout Lombardy, each with its own organisational independence but united in what was called the Autonomia Operaia milieu. The new headquarters became the former Gruppo Gramsci building in Via Disciplini. A meeting also took place with the Fronte Unitario Omosessuale Rivoluzionario Italiano (Italian Revolutionary Homosexual Unity Front) (‘Fuori’), with which the magazine Rosso collaborated for some time.

The most militant workers’ collective of the CPO was that of Face Standard and the Sit-Siemens collective was also very important. In Milanese schools, the Coordinamento collettivi autonomi studenteschi (Coordination of Autonomous Student Collectives) was formed, whose members were present in schools in the city centre (Berchet, VIII Itis, Parini, Galilei, Ingegneria). Youth groups developed in the neighbourhoods of Baggio, Stadera, San Siro, Lambrate, and in Rho, the Coordinamento degli organismi autonomi (Coordination of Autonomous Organisations) organised the self-reduction of transport and utility bills in its area. On the 6th of October 1974, an entire warehouse belonging to Face Standard, a company owned by the multinational ITT accused of supporting the Chilean fascist coup (11th of September 1973), was set on fire and destroyed. No similar attack on an industrial plant had ever been carried out in the Milan area. The action was part of ‘Rosso’ and sparked a discussion within the organisation about the forms of struggle that involved the entire organisation behind the operation. The leaflet claiming responsibility was distributed for a week in factories, schools, and venues frequented by left-wing militants and cinemas.

1974 began with a strong resurgence of workers’ initiatives, particularly at Magneti Marelli, Breda, Telettra, Falck, and in the chemical sector, at Borletti and Pirelli. On the 7th of February, a series of national mobilisations of metalworkers, chemical workers and textile workers began. During the Milan march, the premises of the Monarchist Federation were devastated. This continued on the 20th of February with a strike in most large industries. On the 27th of February, a new general strike led to the resignation of Treasury Minister Ugo La Malfa.

1974 was the year of the referendum victory against the abolition of divorce, but also of fascist massacres: on the 28th of May 1974, during a trade union demonstration in Piazza della Loggia in Brescia, a bomb hidden in a rubbish bin killed eight people and injured around a hundred; on the 4th of August 1974, a bomb exploded on a carriage of the Italicus train as it emerged from the Grande Galleria dell’Appennino tunnel near San Benedetto Val di Sambro, in the province of Bologna, killing twelve people and injuring 155. After the Brescia massacre, the mass response was overwhelming and marked by militant anti-fascism.

On the 8th of September, Fabrizio Ceruso died in Rome, in the working-class neighbourhood of San Basilio, during violent clashes between the police and squatters backed by revolutionary militants. Several days of violent clashes followed, with both sides using firearms, but in the end the police were forced to leave.

The wave of militant anti-fascism and the use of firearms during a demonstration became a topic of debate in the national workers’ autonomy movement and therefore also in Milan. In fact, for some sectors, it became necessary to consider “arming the masses”.

From the 13th to the 16th of June, the Festival del proletariato giovanile (Youth Proletariat Festival) organised by the magazine Re Nudo took place in Milan’s Lambro Park. The event was so successful that it was repeated in Lambro Park for the next two years.

In response to the government’s decision to increase electricity, telephone and transport tariffs, a mass campaign for self-reduction spread throughout Italy from August 1974. Within the autonomous area, actions were organised to target the SIP telephone exchanges, tens of thousands of ENEL electricity meters were tampered with, and the practice of not paying public transport tickets became widespread. As part of the self-reduction campaign, the so-called ‘long strike’ against the high cost of living began in Lombardy on the 30th of September. In this context, on the 19th of October, proletarian expropriations were carried out against two supermarkets in Quarto Oggiaro and Via Padova. For Rosso, this was a concrete example of what was meant by ‘the relationship between avant-garde experience and mass illegality’.

The different assessments of the strength of the workers’ struggles and of the historic compromise proposed by the PCI also opened a rift within Lotta Continua. There was a division between the neo-institutional option of the majority of the leadership on one side and the choice to further radicalise the conflict by those who then chose to leave the organisation on the other. The official position of Lotta Continua was drastic: faced with the perpetuation of reformist hegemony, it was necessary to take the average point of view of the working class and rethink the relationship with its grassroots organisations and with its own working-class base.

Those who criticised this position left the organisation, in particular the Lotta Continua headquarters in Sesto San Giovanni, a working class suburb of Milan. These militants, together with a section from Potere Operaio, decided to form the Comitati Comunisti per il Potere Operaio (Communist Committees for Workers’ Power) in late 1974. Shortly thereafter, the Corrente and the Frazione, groups within Lotta Continua that had emerged from the January 1975 congress battle, also joined the Committees. They were mainly workers from Magneti Marelli in Crescenzago, Falck in Sesto San Giovanni, Telettra in Vimercate, Carlo Erba in Rodano, the Lenin Circle in Sesto San Giovanni, the neighbourhood collectives of Cinisello Balsamo, Cormano, Ticinese, Romana and Sempione, and the security services of some Milanese neighbourhoods (‘Senza Tregua’).

Meanwhile, so-called ‘proletarian rounds’ (which were a kind of workers’ patrols) against overtime were developing in the Milan area. In Sesto San Giovanni, Cinisello Balsamo, Crescenzago and Viale Monza, on Saturdays they swept through small and medium-sized factories, neutralising the guards and throwing out anyone who was working. Proletarian expropriation practices also grew, as did the unauthorised reduction of bills and public transport season tickets.

THE ASTONISHING GROWTH OF WORKERS’ AUTONOMY

The most important political-military event of 1975 was “the days of April” (16th to 18th of April), following the murders of Claudio Varalli and Giannino Zibecchi by fascists. These were the baptism of fire for the Autonomia milieu in Milan (Comitati Comunisti, Rosso, Alfa Romeo), and the street protests changed their composition and became more radical. The April Days showed that the time for trade union parades was over. The practice of real armed squads, of security units that broke away from the march to carry out a series of attacks, became established. The backbone of the marches of those days was gathered behind the banner of the factories of Sesto San Giovanni, which united the most combative workers, demonstrating that the Autonomia Operaia existed as a political entity. At the same time, attempts by groups (Avanguardia Operaia, Lotta Continua, and the Student Movement in particular) to confine the great potential expressed by this new generation of militants within the outdated framework of militant anti-fascism failed. The new season of struggles was all about autonomy, with new collectives in factories, schools and neighbourhoods emerging as autonomous entities, as did their struggles. The organisational model of the old groups had failed, and the practice of appropriation developed (reductions of general household bills but also the self-reductions at rock concerts), along with patrols against illegal work and heroin dealing, the occupation of buildings, the creation of the first self-managed spaces (the Fabbricone in Via Tortona, the Virus in Via Correggio 18, the Leoncavallo, the Garibaldi, the anarchist social centre in Via Conchetta, but also the centres in Stadera, Barona, Baggio, Città Studi, Lambrate, Casoretto, Romana Vittoria and Corso Garibaldi).

Other components of Milanese autonomy include the Autonomous Communist Collectives, which bring together the Argelati Social Centre, the Panettone Social Centre, the Carlo Sponta Centre for the Fight Against Illegal Work, and the Autonomous Comrades of Romana-Vigentina.

A little further north, there are the Coordination of Autonomous Organisations in the Rho area, the Autonomous Committees of the Venegono-Tradate area, the Political Committee of the Busto Arsizio area, the Coordination of Autonomous Committees of the Saronno-Caronno area, and the Anarchist Coordination of the Legnano area. In the Bergamo and Lodigiano area, the Autonomous Political Collectives were active.

The year ends with a crescendo of initiatives in the factories, particularly at Magneti Marelli against restructuring and political dismissals (Magneti Communist Committee) and at Innocenti, which was undergoing profound restructuring (Innocenti Workers’ Coordination Committee). The submissive attitude of the trade union in the face of the dismantling of Innocenti became the clearest example of reformist ‘collaborationist’ action. Among the various episodes that marked the dispute, on the 29th of October, during the general strike, an autonomous procession first occupied the Lambrate station and then attempted to enter the nearby Innocenti factory to show solidarity with the workers in struggle, but found the road blocked by the union security service backed by Avanguardia Operaia: physical confrontation was inevitable and led to the proclamation of the ‘end of workers’ unity’.

On the 17th of January 1976, feminists from Milan organised a demonstration for abortion in Piazza Duomo, during which they entered the cathedral to protest against a centuries-old place of repression of women (feminist collective of Via Cherubini).

On the 6th of February 1976, the trade unions called a four-hour general strike in Milan. Bruno Storti’s CISL rally was contested by revolutionary left-wing groups who attempted to storm the trade union stage. The demonstration ended with an autonomous march to the Central Station, which was occupied.

In the same month, at the Teatro Uomo, the play La traviata norma was presented, organised by the autonomous homosexual collective, whose protagonist was Mario Mieli.

On the 8th of March, the autonomous feminist comrades organised a fierce counter-demonstration in front of the entrance to the Mangiagalli clinic.

On the 25th of March, during the general strike against the economic crisis and price increases, demonstrations took place throughout Italy, ending in some cities, such as Naples and Bergamo, with a full-scale assault on the prefectures and looting of shops in the city centre. In Milan, the march occupied the Lambrate railway station and numerous companies were ransacked. During the demonstration, the municipal tax office in Piazza Vetra, the Dalmine sales office, the Ras offices, the headquarters of the Milanese insurance company and the headquarters of Confapi (Association of small and medium-sized private companies) were all attacked.

On the 10th of April 1976, a proletarian expropriation at the GS supermarket took place in Bresso; the action was repeated on the 23rd of April at the UPIM in Cologno Monzese; on the 20th of May at the Esselunga in the Bovisa district; and on 22nd of May at the Esselunga in Via Bergamo.

Also in April, a group of young people interrupted Francesco De Gregori’s concert at the Palalido to protest his phoney affiliation with the movement and the excessive cost of his concert tickets. In the following months, the young proletarians thwarted Comunione e Liberazione’s attempt to organise a concert by Alan Stivell, which was cancelled after threats and attacks against the Catholic organisation’s headquarters; the youth clubs decided to intervene ‘critically’ at the Antonello Venditti concert organised by the ‘democratic’ radio station Canale 96.

On the 2nd of April, an armed group stormed the gatehouse of Magneti Marelli in Crescenzago and shot the head of the factory security in the legs: the workers’ committee boycotted the one-hour protest strike called by the unions. Not a tear, not a minute’s strike for the head of the guards, read the committee’s leaflet.

On the 29th of April 1976, Enrico Pedenovi, a provincial councillor for the fascist Italian Social Movement, was shot dead in Milan: it was the first intentional political murder claimed by the left in Italy in the 1970s. The action was a militant response to the fascist attack that cost the life of Gaetano Amoroso, a comrade of the revolutionary left, and should be seen in the context of intense squadrist, meaning fascist, activity in the Lombard city.

A few months later, Senza Tregua came to an end following an internal split over a number of fundamental issues. In particular, part of the Communist Committees levelled harsh accusations at the leadership, which they claimed was made up of individuals rather than political representatives, characterised by intellectualism, working according to a rigid division of tasks and not promoting internal debate. The consequence of these dynamics led to the coexistence of different political projects and the consequent failure of the organisational project. The break-up of Senza Tregua led to the formation of three different organisational projects: Prima Linea (PL), Unità Comuniste Combattenti (UCC) and Comitati Comunisti Rivoluzionari (CoCoRi).

In the general election of the 20th of June 1976, the electoral alliance of Democrazia Proletaria (Avanguardia Operaia, Lotta Continua, Partito di unità proletaria (PDUP), Movimento Lavoratori per il Socialismo) aimed for a ‘government of the left’, despite the fact that the PCI had no intention of involving DP and indeed reaffirmed its loyalty to NATO and the theses of the historic compromise. Democrazia Proletaria (DP) aimed for 6-7%, and it was clear that the election result would decide the future of the ‘old’ extra-parliamentary left. The election campaign was very violent. The result was disappointing: the PCI did not overtake the DC, and Andreotti’s so-called ‘government of abstentions’ was appointed. The DP achieved 1.5%, a percentage that marked the definitive crisis of the ‘political groups’ (at the next national congress, Lotta Continua dissolved with a further transfer of militants to the Communist Committees and the movement). Despite this result, however, the groups refused to return to activism, condemning themselves to parliamentary irrelevance. Alongside this choice to focus on the electoral sphere, their crisis can also be explained by the so-called ‘crisis of militancy’ and the ‘astonishing’ growth of workers’ autonomy (which openly sided with electoral abstentionism).

On the 10th of July 1976, a valve burst at the Icmesa plant in Seveso, releasing a significant amount of dioxin that polluted the surrounding area. The environmental disaster revealed the role of multinationals in Italy, but also that of politicians at all levels, the Catholic Church, doctors and researchers. The intervention of the Comitato popolare tecnico-scientifico (Technical-Scientific People’s Committee), made up of workers and students from the area, but also workers from Carlo Erba, the Milan Architecture Collective, doctors and scientists, was important. Their aim was to clarify the indissoluble link between harmful production, capitalism and war, and to introduce a participatory method among the population of the area based on direct knowledge and first-hand action in defence of their health (‘Volantone Contro le produzioni di morte’ di Rosso vivo e Senza Tregua).

In the Milan area, the strongest autonomous workers‘ organisations are the Alfa Romeo Coordination Committee, the Sit-Siemens Political Collective, the workers’ committees of Magneti Marelli in Crescenzago, Carlo Erba in Rodano, Telettra in Vimercate, Falck in Sesto San Giovanni and Philco in Ponte San Pietro, and the Fargas and Fiat OM struggle committees. These formations and these points of strength became the driving force behind autonomous workers’ struggles, even in objectively weaker areas such as small and medium-sized factories. This was especially true in the Milan area, where the Milanese Autonomous Workers’ Coordination Committee (promoted by Senza Tregua, Rosso and PC(m-l) I) was formed, which organised strikes and autonomous demonstrations of some importance between 1976 and 1977. In Milan, there was also the Coordinamento per l’occupazione dell’Alfa Romeo (‘Senza padroni’, ‘Without bosses’) and the Coordinamento lavoratori e delegati della zona Romana (‘Workers’ and delegates‘ coordination of the Roman area’), which was linked to Lotta Continua.

One of the key episodes of the autonomous workers’ initiative of the period took place at Magneti Marelli. After a tough struggle against restructuring, which saw the violent invasion of the company’s offices, four leaders of the Committee were dismissed by the company for their political activities within the factory. However, every morning these workers were brought to the factory by a workers’ procession (the Red Guard) against the will of the owner, the union and the court that had confirmed the owner’s measures, and they became full-time revolutionaries. This practice continued for a whole year. The Milan labour court issued contradictory rulings, with the verdict changing at every level of jurisdiction: decrees of reinstatement and confirmations of dismissal alternated. When the labour court discussed the labour case, it was regularly invaded by workers’ marches, with frequent clashes with the Carabinieri inside the Milan Palace of Justice itself.

In July, hospital workers began a contract dispute in Milan, which escalated to the point that the army had to intervene to ensure that hospital canteens remained open. (Policlinico Collective, Niguarda Struggle Committee, Autonomous Comrades of San Carlo).

On the 20th of October, during a general strike, numerous armed groups operated during the Milanese trade union march, attacking and setting fire to offices and computer centres of large companies, looting a supermarket and destroying the headquarters of the clerical-fascist Comunione e Liberazione (CL).

On the 30th of November, during a new general strike, the Milanese Autonomia Operaia and the PC(m-l) I organised a march independent of the trade union rallies. The demonstration brought several thousand workers, proletarians and students to the streets ‘for the development and organisation of a class opposition’ and against the bosses’ attack, the government of abstentions and trade union collaboration.

On the 15th of December 1976, Red Brigades militant Walter Alasia (after whom the Milanese column of the organisation was later named) was killed in Sesto San Giovanni during a gunfight with the police, in which two officers also died. Alasia was a former militant of Lotta Continua who was well known in Sesto. His death caused a stir in the media, in the trade unions and, above all, in the revolutionary movement. What happened in the Milanese factories during his funeral was proof that armed struggle was part of the mass debate, especially among workers. The most significant event was the political battle fought in factories such as Marelli, Breda and Falck, where workers’ committees opposed the strike against terrorism called by the PCI and the trade unions, judging it anti-worker. Alasia’s funeral was also important, attended by hundreds of workers and militants from Sesto who remembered him as one of their own.

In this context, youth proletarian circles developed rapidly, so much so that it can be said that 1977 in Milan was anticipated by the young proletarians of the suburbs, with house occupations, free cinema admissions and supermarket raids. The first signs were felt in Milan between 1975 and 1976, when large numbers of young people from the extreme suburbs of the metropolis spontaneously formed groups based on their criticism of the miserable social conditions that surrounded them: students, unemployed, precarious and underpaid workers. For them, there was the problem of ‘free time’, experienced as a compulsory obligation to emptiness, boredom and alienation. Starting from this awareness, the Circoli del proletariato giovanile (Youth Proletariat Circles) were formed, which, within a few months, promoted dozens of building occupations, even in the centre of Milan. These places became meeting places for the Milanese youth proletariat and were hugely successful. The Circoli poured into the city centre from the suburbs, no longer in gangs or small groups but to have fun openly, organising music festivals or clashing with the police and demanding their right to gather, party and ‘reclaim their lives’. During these demonstrations, increasingly explicit forms of reappropriation of goods began to be practised, with the expropriation of luxury shops and food stores.

In the first phase, the youth proletariat circles found organisational support in already established political and cultural structures such as ‘Re Nudo’, which closely followed the youth circle movement.

In June 1976, the Lambro Park festival took place in Milan, organised by ‘Re Nudo’ and part of the revolutionary left: anarchists, Lotta Continua and autonomists. It immediately presented itself as a mega gathering, attracting 100,000 young people from all over Italy. Political and cultural contradictions exploded violently, suddenly revealing the limits of the ideology of the festival. The outcome of the festival also marked the definitive split between the counter-cultural practices of ‘Re Nudo’ and the Autonomia Operaia (Workers’ Autonomy) movement. The latter reflected deeply on the outcome of the festival to explain its failure and offer a direction for the struggle that would allow the movement to avoid becoming bogged down in its apparent crisis.

Rosso wrote: ‘Squatting, supermarket takeovers, wage struggles, organisation against heroin dealing, liberation movements and the explosion of the feminist movement all played a leading role in this festival and signalled the death of the Re Nudo Pop Festival. One thing was clear to everyone: that the young proletarians want to party to have fun, but also to assert their needs. And these go against the order of the capitalist metropolis, against the work in the factories of capital, against the repression of the culture of the bosses. The young proletarians want to party against all this. The tension to leave Lambro Park, now seen as a ghetto, and to take the party into the city, against the city, is the achievement of this festival. The suggestion made by many comrades at the festival to return to the neighbourhoods with the ideas expressed in the appropriations and in the assembly is a programme of political work and continuity. It is the awareness of the need to reunify the struggle by the youth proletariat at Lambro with the struggles of the workers against work, with the struggles of the unemployed for wages, with the attack of the prisoners on the repressive state, with the rejection of male oppression by women. Let us return to the neighbourhoods and factories so that the flower of revolt that has blossomed at Lambro may multiply into a hundred flowers of organisation, into a thousand episodes of appropriation, into solid bases of counter-power. For the ability to organise a great festival for next year: our festival against the metropolis.” And this then happened.

In the autumn, the Workers’ Movement for Socialism (MLS) decided to transform its neighbourhood anti-fascist committees into youth clubs. This decision raised many concerns, as it was well known that the MLS had a pro-Stalinist political position and was strongly opposed to countercultural tendencies, the opposite of what the youth proletarian movement declared. The relationship between these youth clubs and the proletarian youth clubs ended, at the end of the year after lengthy disputes, with an inevitable split.

The emergence of the circles marked a revival of vitality for the entire Milanese movement, with the promotion and implementation of a campaign for the self-reduction of cinema ticket prices and against the distribution of third-rate films in suburban cinemas. For several Sundays, thousands of young people reduced the price of tickets for first-run cinemas to 500 lire.

The Milanese youth clubs were deeply rooted in the suburbs of the city, where the local young proletarians represented the new workers of the ‘dispersed’ factory, the protagonists of the decentralisation of production and the underground economy. It was from their own territories that these young proletarians descended into the city centre with its shops and cinemas with the intention of reclaiming, together with the goods they had produced, a part of their own existence. They represented a significant part of what can be defined as a widespread autonomy, which communicated but did not always coincide with the Organised Workers’ Autonomy. Part of this autonomy seeked to dominate the area of the youth circles in order to harness their explosive potential against the metropolis and its contradictions.

This led to the convening, in early November, of the Happening of the Young Proletariat, which took place at the State University in Milan. The manifesto announcing the event depicted a huge tomahawk with the slogan: We have unearthed the hatchet. During the conference, the decision was taken to boycott the opening night at La Scala. ‘In the midst of sacrifices imposed on the proletariat, the rich Milanese bourgeoisie allows itself the thrill of paying 100,000 lire for a seat at the opening of the La Scala theatre season’.

On the 7th of December, the area surrounding the Milanese theatre was manned by 5,000 police officers in riot gear. It was an evening of violent clashes that ended with 250 people detained, 30 arrested and 21 injured. Shortly afterwards, the city’s coordination of youth circles was dissolved, many neighbourhood struggles were disoriented and looked to new organisational proposals. The consequences of the disaster also had repercussions within the Milanese autonomous area. Senza Tregua had already declared itself sceptical about identifying the young proletariat as a possible political subject; in Rosso, a debate developed on the forms of struggle and organisational choices to be made, coming to the conclusion that a tight organisation was needed to formalise the presence of a logistical structure within each collective. The Communist Brigades were formed.

Between 1976 and 1977, militant and illegal actions against ‘black work’ (attacks and raids on companies and small businesses which employed people informally), proletarian expropriations against clothing stores and supermarkets, attacks against heroin dealing spots, repressive institutions (carabinieri, police, traffic police, prisons), and the Christian Democrats multiplied.

In particular, in Milan (late 1976-mid 1977), a strong militant initiative developed, centred on workers’ patrols, so called ‘proletarian rounds’, against places of illegal employment and the ‘dispersed factory’. The patrols were informal organisations that sprang up in the city’s neighbourhoods (Lambrate, San Siro, Ticinese, Romana-Vittoria, Bovisa, Mecenate). The patrol was an exercise of power in the practice of appropriation, taxation of managers, punishment of bosses and security guards. The proletarian round was an exercise in attacking centres of power and anti-worker restructuring (business centres, computer centres) and the bodies that manage public services in the area (transport, electricity, telephones). It was a mass organisation because, by immediately gathering all the forces of autonomous organisation, it overcame and broke down the division between workers, unemployed, young people and neighbourhood vanguards. It was a project of organisation because it expressed and synthesised all levels of attack by autonomous initiative. There are dozens of interventions by proletarian rounds that targeted those micro-departments scattered throughout the suburbs, often on behalf of multinationals, with the complicity of trade unions and local authorities, and which, in the face of the crisis, used overtime on Saturdays, dismissed people who were on sick leave, exploited illegal labour, and paid low wages to produce low-cost, high-profit goods.

AND SO WE COME TO 1977

The area of organised autonomy in Milan has always been extremely varied and has never had a hegemonic group like the Volsci in Rome or the political collectives in Veneto. During this period, the main political forces were those who gathered around the theses set out in the magazine Rosso (the political workers‘ collectives) and Senza Tregua (the Communist Committees for Workers’ Power).

The Rosso milieu identified the so-called ‘social worker’ (a figure that goes beyond the immediate large workplaces) as a political subject, which was born out of the dispersal of factories across the territory following economic restructuring. The restructuring made it extremely difficult for workers to regroup within large factories. In this way, the conflict was reduced in the factories, but spread throughout the territory, affecting people’s social lives, and thus the clash took on a global character, affecting people’s entire lives, not just their workplace. At the factory level, Rosso was very present at Siemens, Face and Alfa (CPO), and organised Student Political Collectives in schools, particularly at the Berchet classical high school. The Communist Brigades emerged from its debate forum, which then led to the formation of the Formazioni Comuniste Combattenti (Communist Combatant Formations).

Senza Tregua called for the mass arming of workers and a workers’ decree, identifying itself with the central role of workers (those in large factories) and was well represented at Magneti Marelli in Crescenzago, Innocenti in Lambrate, Philco in Brembate, Telettra in Vimercate, Carlo Erba in Rodano and Falck in Sesto San Giovanni.

To these two main groups must be added the collective from the working-class neighbourhood of Casoretto, also known as the ‘Bellini gang’, which had a formidable security service. The Communist Committee (Marxist-Leninist) for Unity and Struggle, CoCuLo (magazine ‘Addavenì’); the Italian Communist Party (Marxist-Leninist) (‘La voce operaia’); the Coordination of Autonomous Organisations in the Southern Zone (Via Momigliano); various anarchist groups (‘Collegamenti Wobbly’) and situationist groups (‘Gatti selvaggi’, ‘Puzz’). To these sectors must be added a feminist component not directly associated with any of these positions but close to autonomy (the Via dell’Orso collective); young people from the neighbourhood collectives (Romana-Vittoria, Baggio, Barona, Lambrate, Bovisa, San Siro, Stadera, Sempione-Garibaldi, Gallaratese, Olmi, Cesano Boscone, Arese-Rho-Pero); part of the youth proletariat circles; and the Coordination of the Workers’ Opposition (Alfa Romeo).

It is impossible to understand the highly complex autonomous reality of Milan without realising that, alongside the militant organisations, an incredible number of mobile and informal micro-organisations had formed in the city, spreading armed struggle from the metropolis to the most peripheral centres, favouring attacks not so much on the ‘heart of the state’ as to the figures who constitute ‘the articulation of capitalist command over the territories’. Alongside those who were active in the official combatant groups such as Prima Linea and the Red Brigades, within the organised Autonomy many comrades, often very young, formed micro-aggregations based on affinity. These were often linked to territories such as the working-class neighbourhoods where they lived, to school collectives or collectives formed to fight militantly against the spread of heroin or to attack ‘black labour dens’ (both forms of exploitation are experienced first-hand). They also organised armed actions or expropriated luxury shops. This area was fluid, with no real fixed organisational structures, and their credibility was often entrusted to the ‘piazza’, the public city squares. The more organised autonomous groups (including combatants) tried in every way to draw these groups to their side, in a relationship of symbiosis (the official groups provided logistics, the micro-groups act) rather than real co-optation, but the result, at least throughout 1977, was disappointing.

The explosion of armed initiatives in the Milanese metropolis gave the fighting organisations the possibility of recruiting militants. In this context, the Communist Brigades were formed in the ‘Rosso’ milieu with the aim of stemming the exodus of militants from the Autonomia towards the official organisations of armed struggle, seeking to relate acts of sabotage and counter-power to the figure of the social worker. The organisational experiment was short-lived and by the summer of 1977, the Communist Brigades had disbanded over differences in the understanding of the functions and aims of an armed organisation. This experience gave rise to the Communist Combatant Formations, while other militants joined the Proletari Armati per il Comunismo, Guerriglia Rossa, Prima Linea and Brigate Rosse.

All Italian universities were in turmoil, protesting against the university reforms proposed by the Minister of Education, Franco Maria Malfatti. In February 1977, like in many other cities throughout Italy, the state university in Milan was occupied.

On the 26th of January, trade unions and Confindustria signed an agreement at the CNEL headquarters on reducing labour costs and increasing productivity. Workers’ reactions to the news of the agreement were immediate but sporadic, with workers in some factories going on strike independently: Ctp Siemens, Fiat-Om, Magneti Marelli and Ercole Marelli in Milan.

On the 8th of March an extremely well-attended mobilisation of the feminist movement took place, which marched through the streets and squares and reaffirmed its autonomy not only from parties and institutions but also from the student movement itself. In Milan, the feminist groups in Via dell’Orso and at Bocconi University organised a ‘militant’ demonstration with the political objectives of protesting against INAM, which was fighting absenteeism among female workers, the Mangiagalli gynaecological clinic, which refused to perform safe abortions, and Luisa Spagnoli’s shops, accused of exploiting the labour of female prisoners.

On the 11th of March, in Bologna, a carabiniere killed Lotta Continua militant Francesco Lorusso, which was followed by days of violent street clashes that led to tanks being deployed to guard the city streets. The next day, a national demonstration of the movement took place in Rome, turning into one of the most violent marches in Italian history. On the same day, in Milan, during an extremely combative march, a part of the march broke out and shattered the windows of the Assolombarda headquarters.

During the general strike on the 18th of March, an autonomous workers‘ march paraded through the city centre, attacking numerous targets, in particular the Marelli management building (for the dismissal of workers’ vanguard and restructuring) and the offices of Bassani Ticino (for the exploitation of underpaid female prisoners in San Vittore). Commenting on the march, the entire Milanese autonomous workers‘ movement claimed that the revolutionary nature of the demonstration was the result of the break in worker unity brought about by the workers’ left against the PCI and the trade unions.

In April 1977, seven militants of the Communist Committees for Workers’ Power were arrested by the Carabinieri on their return from a firearms training exercise in Valgrande: they were workers from the Milan area (Falck, Magneti Marelli). The workers’ committees of Magneti and Falck handled the arrests politically, claiming the right to arm the workers in the face of the anti-worker terrorism of the bosses. They distributed a leaflet at a Trentin rally in Piazza Castello in Milan. The text stated that the small and medium-sized merchant bourgeoisie were arming themselves, that the bosses had their own private armed forces, and that it was therefore legitimate for the workers to do the same. At the trial, the courtroom was full of comrades chanting slogans of solidarity. Shortly after the trial, elections for the delegates‘ council were held at Magneti Marelli. Enrico Baglioni, one of those dismissed and arrested in Valgrande, was among the first to be elected.

On the 1st of May, the Milanese Autonomia organised a well-attended counter-demonstration led by the workers’ collectives of Face and Siemens.

On the 12th of May, the two lawyers of the Soccorso Rosso (Red Aid), Sergio Spazzali and Giovanni ‘Nanni’ Cappelli, were arrested in Milan. The following day, Giorgiana Masi was killed by plainclothes police in Rome. The Milanese march on the 14th therefore took place in a particularly tense atmosphere. The demonstration marched near the San Vittore prison, where the two lawyers were being held. A group broke away from the rest of the demonstrators and opened fire on the police, seriously injuring two officers and killing a third.

The episode had major consequences within the Milanese Autonomia movement, creating a rift between those pushing for an escalation of the conflict and a centralised organisation of micro-groups, those who openly criticised the episode and those who saw it as the possible end of the autonomous city movement. The youth proletarian circles were in a deep crisis, feeling the pressure of an increasingly harsh confrontation, which in Milan appears ungovernable.

The clash with the Workers’ Movement for Socialism also intensified. They were accused of being Stalinist, in cahoots with the trade unions and with the owners of some houses occupied by the proletariat, particularly in the popular Ticinese area of the city.

The crisis of the 1977 movement became evident at the conference against repression held in Bologna in September. In the following months, the Milanese Workers‘ Political Collectives and the Venetian Political Collectives for Workers’ Power (which merged their newspapers, Rosso and Per il potere operaio into Rosso per il potere operaio) agreed on the urgent need for a national political and organisational project for the various factions of the Organised Workers‘ Autonomy. They proposed the Party of Autonomy, first of all to the Roman Autonomous Workers’ Committees (the Volsci), who rejected the idea.

In the autumn of 1977, in Milan, struggles against repression (continuous arrests of autonomous militants) and against the increase in public transport fares exploded with marches, roadblocks and mass sabotage of ticket machines.

Of particular note was the march on 12 November protesting against the closure by the judiciary of several autonomous headquarters in Rome and Turin; the demonstration was marked by the disarming of numerous traffic police and vigilantes and an armed assault on the Polfer (railway police) at the Porta Genova railway station.

The struggle in Milanese hospitals continued unabated with marches and assemblies, but also with dismissals, arrests and trials of the movement’s leaders.

On 26 December, Mauro Larghi, a leader of the Saronno student movement, died in prison in suspicious circumstances. He had been arrested a few days earlier on charges of disarming a police officer.

FROM MORO TO THE 7TH OF APRIL

In 1978, Rosso focused its mass work in particular on the struggle against working Saturdays at Alfa Romeo, published the magazine Black Out (and later Magazzino) and launched Radio Blackout.

The struggle in secondary schools gained momentum, and the Coordinamento degli organismi proletari della scuola (Coordination of Proletarian School Organisations) was formed. It reached its peak with the campaign for the ‘6 politico’ (promotion of school students without having to go through arbitrary exams) carried out by Cesare Correnti’s Collettivo politico autonomo (Autonomous Political Collective) on the basis of a leaflet also signed by the Collettivo autonomo chimici di Bergamo (Autonomous Collective of Chemists of Bergamo) and the Collettivo del IX Itis di Milano (Collective of the IX Itis of Milan).

Relations with the Workers’ Movement for Socialism were increasingly tense, with countless attacks against autonomous militants and sympathisers, most notably against the painter Fausto Pagliano in the Ticinese district. To protest against what they considered to be misinformation, the Milanese autonomists occupied the Popolare radio station for half an hour.