Developing a revolutionary strategy for the years ahead

We document this text written by a comrade of ours. Enjoy!

This is the text of a pamphlet written for a talk and discussion at the 30th Earth First! Summer Gathering in July 2024 by someone involved in Earth First! and various ecological direct action groups and collectives in the 1990s and early 2000s. Send any comments on the text to material_struggle@protonmail.com

Why this topic?

Things are pretty fucked. Take any point in time from the previous five or so decades and compare it to today and by almost any metric we’re in a worse situation now than we were then. I don’t mean in terms of rights, individual freedoms and small specific gains in some parts of the world, but in terms of being closer to a post-capitalist egalitarian and ecological world. So those of us that consider ourselves in favour of such a world need to admit that no matter our exact politics and activity we’ve pretty much failed – and are continuing to fail. If this is the case then we need to have a ruthless look at what we do and make it, for want of a better word, work.

None of the things I’m saying here are my ideas or theories, nor are they even new, in fact to some extent they’re ideas and methods that used to be commonplace on the radical left but are now somewhat marginal. This essay and the ideas within it are also not set in stone but are a work in progress – an attempt to articulate and clarify a revolutionary strategy, an adaptable praxis rather than a fixed ideology, and one that’s very open to criticism and change.

Where are we now?

We live in a capitalist system, by this I mean a system that produces commodities for markets to make profit for capitalists, rather than being produced and distributed freely according to people’s need. Capitalism needs a society divided into classes; very simply a class that has to sell its labour to survive (proletarians) and a class that owns the means of production (capitalists). This importantly means we can’t separate capital and class in our analysis of the situation, its problems and possible solutions. Capital and its ideological foundations are not restricted solely to production, although that is its fundamental arena. It now permeates all aspects of our lives to the point where we sometimes struggle to comprehend anything outside of it, and we also often act politically as if we can’t – the capitalist is in your head alongside the cop. As a friend once quipped, “What would we do if we thought we could actually win?” There’s also important discussions around nationalism, patriarchy, and racism and how they are related to capitalism and class, but that’s (far!) too much for this short essay to cover.

On a macro level in this capitalist world we have climate change, widespread ecological destruction and habitat loss, and a situation where we see some states hurtling towards a potentially catastrophic global war, and others joining the growing list of failed (or failing) states. On a micro level there’s also a daily struggle just to survive for many, as well as a widespread crisis of everyday life with deteriorating health (especially mental), the growth of various oppressive belief systems and behaviours (extreme religions, patriarchy, conspiracist and racist views among them), and hyper-exploitative work conditions.

Defining our goals

I think there’s a problem when discussing this topic where we often argue about what to do without discussing what our politics actually are. If we use the analogy of map reading our way to a destination, if we don’t agree on the destination then we’re going to disagree on the way we get there. So it’s helpful to agree the destination (or a rough area) we’re heading to, or we could waste our time arguing about routes there when we’re actually wanting to go to different places… or to stretch the analogy further some people have no clear idea where they want to go so weave an incoherent and meandering path to nowhere useful. I sympathise with the view that much of this stuff actually gets worked out and created through struggle, and so new ways of living and running the world will emerge, but nonetheless some broad overview of the goals are essential.

What do we want?

I used the terms post-capitalist, egalitarian and ecological in the introduction, but I am aware they’re very inadequate. To expand on them slightly… I want a revolution that overturns this world where we’re divided by class, abolishes capitalism as a system of production for profit, and destroys the State as capitalism’s manager. In its place we need to establish a communist world where everyone has equal access to all their needs for a fulfilling, caring, ecological, feminist, free and joyful life. So everything I talk about and do politically takes that as a reference point. If that’s not what you want then the political strategy I’m going to address might not mean that much to you. It does get a bit more complicated and entangled than that when we start thinking about transitions and reforms as well, but I won’t discuss that today, maybe it’ll come up in the discussions.

Revolution is something that commonly gets dismissed as an impossible and unrealistic dream, even among those that see it as a desirable goal. Some research (see the Barker, Dale, & Davidson book in resources) showed that between 1900 and 2014 there were 345 episodes across the globe that could be categorised as events, “that successfully displace a regime and substantially alters the political or social order.”

Their research shows the frequency of these episodes went up from 2.44 annually from 1900-1950, to 2.80 annually from 1950-1984, and then to 4.10 from 1985-2014. And this is without the factors of increasing climate change and other global cataclysms that are coming – crisis creates the potential for change. So situations that are potentially revolutionary are far from being rare, in fact they’re actually increasingly common, and likely to become more so in the next decades.

Revolution covers quite a broad church of events so it’s useful to further define what we mean by it by drawing two distinctions: that of between political and social revolutions. Both involve dramatic and radical struggles, but a political revolution only alters the character of the state, social revolutions also alter the underlying social forms and structures. From our perspective more sense can be made if we also draw an additional distinction between bourgeois and potentially (or actual) socialist, communist or anarchist revolutions. So here we are talking about a strategy for catalysing or taking advantage of a situation where an anti-state anti-capitalist social revolution is a potential outcome.

WTF is strategy?

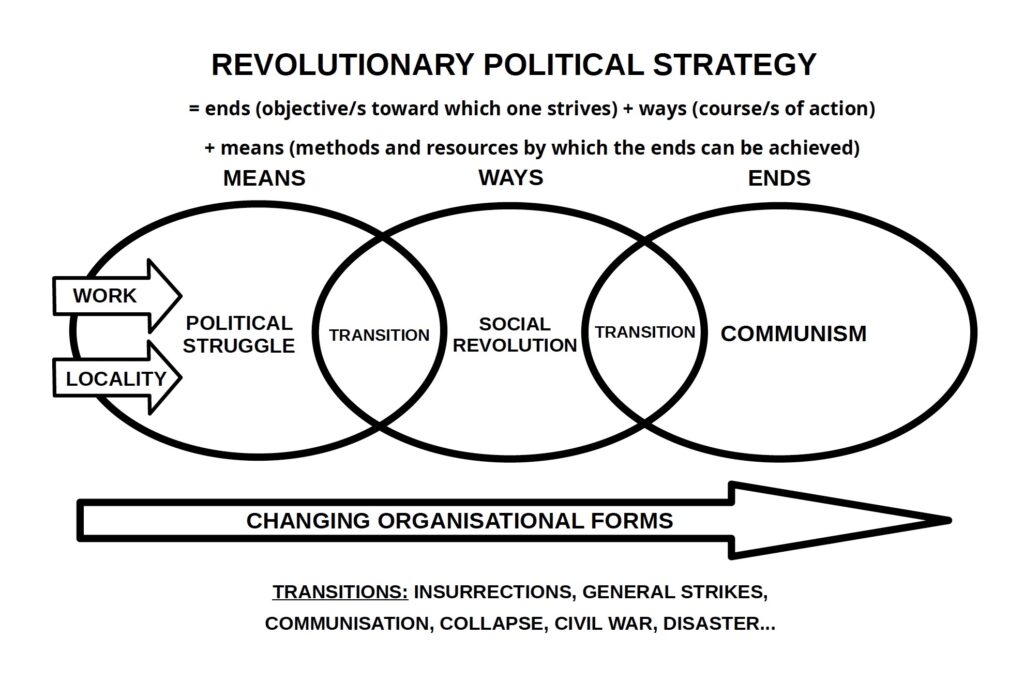

We’ve defined revolution more specifically, but what is a strategy? The classic and easiest way it to think about it is in terms of ends, ways, and means. Ends are our ultimate goal/s; ways are what we’ll do to get there; and means are what we have (or need to build) to get there.

To work effectively they must align and mesh coherently together, both in theory and practice. The issues with other ‘programs’ for revolutionary social change is often the mis-match of some of these, ignoring one or more areas completely, or erroneously elevating a particular form or type of activity into a complete strategy. The three areas also overlap and develop symbiotically, especially in terms of our goal which is a post-capitalist ecological and communist world (ends), and the revolutionary anti-capitalist rupture we want to get there (ways). The other part of the strategy model is the resources and what we have, and need to get, to enable us to achieve our goal (means).

To some extent our political organising can be categorised as building up our means by organising around and towards our ways. One of the differences between vanguard and authoritarian leftists and ourselves is that we’re not building the party or a single organisation, we’re building independent class power in a variety of organisational forms. These also provide political power that can win improvements now through struggle (occupations, sabotage, expropriation, blockades, strikes, go-slows, riots, etc.) and also provide survival and mutual aid structures if we have some form of crisis or collapse. So their use isn’t conditional on having a revolution, it makes our lives better in the here and now too, and they can additionally form part of the basis for future revolutionary and post-revolutionary organisations where we live and work.

So, what to do?

“Meaningful action, for revolutionaries, is whatever increases the confidence, the autonomy, the initiative, the participation, the solidarity, the egalitarian tendencies and the self-activity of the class and whatever assists in their demystification. Sterile and harmful action is whatever reinforces the passivity of the class, their apathy, their cynicism, their differentiation through hierarchy, their alienation, their reliance on others to do things for them and the degree to which they can therefore be manipulated by others – even by those allegedly acting on their behalf.” – Solidarity group (1972).

There’s two critical areas where we need to organise and fight, and when taken as two pillars of the means part of a complete political strategy they also overlap and will catalyse and strengthen one another. One of the significant practical things they have in common is they’re about the material and political conditions of the class rather than moral choices or emotions of the individual, and when taken together they also offer something that everyone can be involved in as everyone works and/or lives somewhere.

Work: Much of work solely serves the needs of capitalism, and as part of a revolutionary process huge amounts can be abolished, some can be automated, and then what’s left and really needed should be shared out more fairly. But in the here and now we do need to have our current work as one of the two primary areas for any political activity.

There are two main reasons for this. Firstly, as mentioned earlier capitalism is a system of production, and as such it absolutely relies on waged labour to survive, so to challenge capitalism we need to address work organisationally and materially through struggle. Secondly, we need the ability to collectively provide the material needs that we require for our survival. Revolutions and insurrections are often won and lost on the basis of who can control key locations and provide what people need to live. If any revolutionary struggle is to succeed then it has to include this seizing control and communising of essential production and services, if not immediately then at least very swiftly before the state can reassert control.

When I talk about organising in work the areas I mean are really the essential industries; mainly food production & distribution, energy, transport, health & care, power generation & infrastructure, logistics & supply chains, and education. There’s a common idea among some on the left (usually the academic or pseudo-academic commentariat) that nearly everyone works as a delivery driver, sourdough co-op baker or freelance graphic designer. In reality the total number working in the time critical sectors of health & care, power generation & infrastructure, and food production & distribution alone is around 9 million people, which works out as around 24% of working age adults in the UK (ONS, May 2024).

When I say time critical I am meaning the areas that really need to keep running through an insurrectionary or revolutionary upheaval with ideally no (or negligible) break in service, whereas other areas such as transport and education are initially far less important. Longer term reinvigorated areas such as local repair shops and light manufacturing will hopefully flourish. There’s also a wide range of new projects and structures that might emerge such as community defence organisations, ecological restoration, expropriated housing allocation, and new decentralised methods of food and power production.

Locality: I’m purposefully using the word ‘locality’ rather than ‘community’ here. We’re not talking about community organising, we’re talking about revolutionary organising where you live. Why is it important? Work is of primary importance under capitalism, but not all people work, and besides many do not work in a workplace that is essential and/or lends itself to organising in. Of course people also experience capitalist exploitation and state control where they live through things like rent and landlordism, poor living conditions, and hostile environment oppression. Building independent class power to resist this and organisational power where we live is an essential component, and while it is less able to challenge capital in the essential productive sphere it can provide a basis that can reinforce our wider class power, especially when we consider the structures needed to resist capitalism and create a post-capitalist world longer term.

Importantly, but less obviously, where we live and how we relate to the area and others that also live there is socially, culturally and (for some) spiritually important. We are deeply social creatures and we need healthy, balanced and caring lives were we look after ourselves and other people, and understanding where we live and the people we live near is something that capitalism has largely broken, and is an area we desperately need to re-discover as part of the wider revolutionary project.

So these two are the critical areas to organise in and around, and having places where they link up is even better, e.g. working in a logistics hub in the area where you live, and some situations like that will hopefully emerge as you get to know where you live and work better.

For both these things to work we need to get to know people, build trust between one another, and to develop and communicate our ideas and activity – and this all takes time. In Rojava in NE Syria the movement there had been working hard for around 40 years listening to people and sorting out their problems, confronting the Syrian regime, engaging in self education and building political structures that were sustainable and robust enough to survive repression and internal conflict.

There’s also the question of undervalued and often unseen socially necessary but usually unpaid labour in the home and family (and also in many workplaces) and mostly undertaken by women. While essential for capitalism to function it isn’t critical in winning any revolutionary situation, but as part of any social revolution will have to see huge changes.

There is also a third area of activity that usually develops more spontaneously and is more chaotic and contradictory, and that is social movements.

What about social movements?

For us in the UK (and much of the rest of the world) in the last 50 years this is how much of the more dynamic extra-parliamentary/radical left politics is expressed. Social movements come and go, and after a brief period of frenzied activity often collapse leaving small increasingly irrelevant remnants of the original movement trying to recreate their prior glory days. Social movements usually arise around an issue or event rather than a locality or workplace, and they often have some limited demands or concerns and a wide variety of political views within them. They can of course challenge capital and state, even if they do not explicitly have those as aims. The anti-roads and some other anti-infrastructure projects arguably challenged the expansion of capital and could in part be seen as a movement against capitalist enclosure. Currently some of the demands of the climate change movement could be seen as such a fundamental challenge to capitalist accumulation that they would require the overthrow of capital, whether or not they explicitly understand or articulate that as a goal. So it’s not about dismissing all issues or campaigns as something irrelevant or unconnected to the struggle against capital and the state, but that structurally the best way of actually winning them is if the resistance comes from people organised at work or where they live co-ordinated across the locality, country – and internationally if possible.

There are some social movements that are much more clearly economic or material conditions based (the Yellow Vests in France for example) as are some of the ones here that have emerged from what is often seen as the right wing or reactionary parts of the working class, for example the UK truckers fuel protests in 2000. Movements are complex and contradictory and understanding and engaging with them politically rather than discounting them on moral judgements of the personal (or even some of the collectively articulated) politics of the people involved is important.

The main failures with social movements are more pragmatic ones about how they are able to have power (or not) to impact capital rather than just be a public order annoyance or short lived social phenomenon, and also how they can provide the necessities for life through any revolutionary upsurge. Of course mostly they are not concerned with this, and are more openly about making demands or requests for the state or other organisations to change slightly, and many of them have little potential to generalise in terms of involvement and/or develop in a more revolutionary direction.

If we do see an emergence of any wider potentially revolutionary social movement, then it is critical that it establishes quick and strong links to militant workers in essential and time critical industries. To not do so limits its activity to street based mobilisations or infrastructure disruption, or in some cases over time it forces it into an increasingly small and militant movement, both of which facilitate the state to be able to crush it.

————— Box ——————–

Crisis of the collective or collective crisis?

In the last decade or so there’s been a widespread organisational crisis in our political groups, projects and collectives. Formal anarchist and left communist organisations have tiny memberships, publications have folded, chronic unreliability is endemic, groups that seem active are sometimes just 1 or 2 people with a social media account, attendance at meetings is low and actual engagement with projects is even lower.

One of the reasons is political differences and the ease with which people often leave projects or groups over minor disagreements – something that’s much easier to do if your political activity is based in individual choice rather than being rooted in where you work or live. The impact of Covid, the shift to online meetings, and importantly people’s lives being harder leaving less time for politics that aren’t integral to their daily lives have all played a part as well.

What also plays a part is a lack of clear ideas about what we need to do, how we need to do it and how it might actually work. Dismissing questions on this topic is a cop-out, and while we can’t (and shouldn’t) have a grand plan of exactly how things will be, we should be able to answer broader questions on how some area of society might work for our visions of the future. Authoritarian leftist organisations with much clearer structures and plans are doing relatively well, and Extinction Rebellion also saw massive involvement in both meetings and activities, despite its strategy having (significant) flaws. I’m not at all suggesting a singular membership or political party type organisation is the solution, but that alongside other problems the lack of a clear and effective political strategy and the collective ability to articulate that plays an important part in our current weak state.

————————–

How do we do this?

What we have now, activism and campaign based politics and subcultural political scenes, are irreparably flawed and broken, and that includes the militant versions of them. The primary reason for this is we’ve been systemically smashed over the previous decades, both by the organised ruling class with violence, and the efficiency and appeal of what capital has provided (or promised) for some. Hand in hand with this (and as a less threatening alternative encouraged by, and often entirely compatible with, capitalism) is this growth in single issue based campaigns and activism making limited demands or addressing specific inequalities or problems. We’re actively encouraged to care, and even take action (within certain boundaries) on this variety of concerns. Left wing politics mostly now takes the form of deciding which of this collection of issues we want to address, all driven by short term thinking, the desire to belong to a subculture, moralism, and personal emotional reactions rather than a revolutionary political analysis and strategy.

In place of this what I’m not suggesting is that we desperately try to expand these anarchist & communist political subcultures, make more ambitious demands, get larger numbers of people involved in our tiny groups or actions, band our organisations together to give the illusion of mass, or put the gloss of a revolutionary class analysis on our campaign leaflets. What I am suggesting is for people to desert the eternally crumbling political scene we have now for something far better, and that will actually work in creating a potentially revolutionary force.

How do we do that? I’ll leave most of the detailed practicalities of how we organise within these areas for the discussion, but I’ll mention broad overviews for the most important areas of work and locality.

Work: get a job in one of the essential industries mentioned above. Don’t be tempted by petit-bourgeois self employment, NGO or co-op jobs. Join a union (see the ‘Unions & strikes’ box for some problems with this…) meet other politicised workers, and organise. Think about how you might seize control of your workplace and run it as workers without bosses or the state. Build autonomous workers power and politics within the workforce; occupy, strike, discuss, struggle, reflect and repeat.

Locality: if you live where you are from stay there, if not move somewhere and stay there, if possible also get a job in the area too. If you need to move choose rural areas, villages, mid-sized towns, or cities without large leftie or activist scenes. We need to understand where we live, who works there and in what industries and workplaces, and get to grips with the problems and the possible solutions. Support one another through things like rent strikes, workplace struggles in your area, and developing local mutual aid networks. Communalise resources, have political discussion groups, grow social networks and build trust and confidence in the people you live near.

————– Box ———————-

Unions & strikes

A predictable route for many people after a few years of activism is something like this; feel burnt out or disillusioned, and then decide the thing that needs to happen is some variety of more ‘sustainable’ long term organising. For those from a direct action or anarchist background that’s usually some form of ‘community’ organising, whereas for those from a more traditional left wing group or political party background it tends to be working within unions.

Unions emerged as a reaction to class conflict, and while they have a role in fighting for worker rights, they also have a role to moderate and manage more radical tendencies within struggles. The promise of trade unions is not only to their members that they can call strikes, but more importantly to the capitalists that they can call them off when things look like they could get out of hand. We repeatedly see that unions channel energy away from collective power and political development and into closed door negotiation processes. This isn’t to say that there is nothing in unions that can be used by workers, but to point out that they hold a structural role in mediating the conflict between workers and capital and are a useful pressure valve to be used by the state in moments of crisis.

In the health service this was demonstrated clearly during the recent strikes. The main issue raised on wards and on picket lines was the chronic understaffing, but instead of taking this up the unions funnelled all of the energy into weak and separate pay demands. Escaping this control of unions and growing a more independent workers dynamic rooted in the wider class (nationally and internationally) rather than being restricted to easily managed demands around wages or conditions in what we should be aiming for.

The impact of the strikes themselves (and other workplace confrontations) is in large part dependent on the industry they occur in. Power generation and public transport strikes will be more impactful than delivery drivers and hospitality industry ones, even if strikes in these sectors may seem more radical on the surface. The potential for strikes to cross both profession and workplace boundaries, to be about more than wages or conditions, and for workers in these struggles to start developing and articulating a collective vision of a new society are key factors in them developing revolutionary potential.

An inspiring example of a struggle that manages to escape the confines of these problems is the GKN factory workers struggle in Italy. In November 2022 GKN, a global automotive manufacturer, threatened to close a plant in Florence where around 500 workers were employed. In order to excuse their blatant relocation in search of cheaper labour GKN said that the closure was necessary due to the demands of the ‘Green Transition’. The workers however, leaning on their collective strength after years of maintaining a permanent factory workers committee, immediately occupied the factory. They drew up plans to switch to the production of mechanical parts for buses and solar panels. They were able to make connections with the climate movement in Italy and the factory is still occupied 2 years later. They used their collective power and productive knowledge to challenge the false logic of green capitalism, and act as an example of the capacity of the working class to not only discuss, but also impose the question of revolutionary transition.

We can imagine if workers in other sectors were able to create such forms of organisation. What could have been done if when P&O ferry workers were attacked by management a couple of years ago they were able to impose restrictions on fossil fuel shipments? If health workers were able to pose a different vision of containing the pandemic that didn’t let thousands die locked in care homes? All of this would of course involve challenging the law, the basis of the state which the unions rely on. Strikes will come up against these limits unless workers are able to develop political forms of collective power that are able to organise their struggles when both the bosses and the unions decide it’s time to pull the plug.

An article and a film giving an overview of the GKN struggle is here https://en.labournet.tv/lets-rise-gkn-factory-collective

————————

In both of these areas don’t be scared of being open about your politics, and develop the ability to speak, discuss and argue convincingly and in public about them. Talk, and importantly listen, to people. Constantly expand our reach and impact, not to ‘recruit’ as we have no loyalty to an organisation, but by using the class, anti-capitalism and revolution as constant reference points. Be able to explain to people clearly what they mean without them glazing over with boredom. Look locally, nationally and internationally for other comrades doing similar, talk to them and learn lessons from one another.

We’ve got a lot of work to do building back independent class power where we live and work. Catalysing the strength and dynamism of a revolutionary left pretty much from nothing (or from a few fragments anyway) requires commitment and a complete shift in how we engage in political activity. Hopefully some of the above starts to make clear what having a revolutionary anti-capitalist political strategy entails and gives some direction for starting to enact it now.

Resources

- Andrew X (1999) Give up activism.

Written in the late 1990s at the peak of the wave of anti-globalisation mobilisations, a classic that addresses the failure of the model of activism and which generated lots of discussion at the time. Touches on the difference between being an activist and a revolutionary and activism and revolutionary organising. Text (including the excellent postscript) here https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/andrew-x-give-up-activism

- Angry Workers (2016) Insurrection and production.

Text and PDF (and lots of other good stuff) here https://www.angryworkers.org/2016/08/29/insurrection-and-production/ Of course there’s the book Class Power on Zero-Hours too. Precarious and unruly class war by any mean necessary!

- Capital by the big bearded man himself, although I recommend attempting it as a reading group as it is pretty hard going. A shorter more accessible book on the topic is Capital Condensed: A short guide to Marx’s Capital for our age of global crises by Colin Chalmers. On class and capitalism anything by Erik Olin Wright and Ellen Meiksins Wood (i.e. The origins of capitalism: A longer view) are also fantastic reading.

- Colin Barker, Gareth Dale, & Neil Davidson (2021) Revolutionary rehearsals in the neoliberal age.

Shows that revolutionary (and potentially so) situations are far from rare. Looks at 9 of these situations and how they happened, developed & concluded, and gives some valuable lessons for us all.

- Dan Evans (2023) A nation of shopkeepers. The unstoppable rise of the petit-bourgeoisie.

Great analysis of the growth of the petit-bourgeoisie class in contemporary Britain. Also worth looking at is stuff on the rise of the Professional Managerial Class (PMC). There’s a good interview to start here https://www.dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/on-the-origins-of-the-professional-managerial-class-an-interview-with-barbara-ehrenreich/ A more academic-ish and longer read is Disciplined minds: a critical look at salaried professionals and the soul battering system that shapes their lives by Jeff Schmidt. It goes into detail about how the education system that produces professionals will almost inevitably produce people that actively work towards maintaining the systems of dominance that perpetuate inequalities.

- Dan Georgakas and Marvin Surkin (1998) Detroit: I do mind dying: a study in urban revolution.

The story of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers and Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement members that did the kind of organising this talk suggests in the car factories of 1960s & ‘70s Detroit.

- David Kilcullen (2013) Out of the mountains. The coming age of the urban guerilla.

Discusses the major factors in war and counter-insurgency strategy for the coming decades: population growth, urbanisation, littoralisation, connectedness, and climate change. Review here https://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/book-review/out-mountains-coming-age-urban-guerrilla

- John Womack, Peter Olney & Glenn Perusek (2023) Labor power and strategy.

A collection of essays and discussions on an analysis of the ‘choke points’ of capital with a view to developing a strategic analysis for workers so they can slow or stop the capitalist expropriation of surplus value. Innit. Probably worth reading in conjunction with the Jane McAlevey (RIP, she died as I was writing this article) book No Shortcuts: Organising for power in the gilded age. Good review of the Womack book here https://catalyst-journal.com/2023/12/john-womack-labor-power-and-strategy-review

- Joshua Clover (2019) Riot. Strike. Riot. The new era of uprisings.

Excellent book detailing resistance to the process of capitalist production and circulation through time, a theory of the riot and riot prime! Good overview here https://marxandphilosophy.org.uk/reviews/14697_riot-strike-riot-review-by-gregory-mccreery/

- Labournet TV (2023) ‘The Loud Spring’

Then film addresses the failure of climate change activism and suggests workers struggle and control of production as an alternative political model. Has a lovely animated section of how a revolution might unfold. The collective are currently making a film about revolutionary transition that will tour the UK when completed. Download ‘The Loud Spring’ from here https://en.labournet.tv/project/loud-spring

- Murray Bookchin (1998) The Spanish anarchists. The heroic years 1868-1936.

The classic account of the hard work that laid the groundwork for the anarchist struggles of revolutionary 1930s Spain.

- Phil A Neel (2018) Hinterland. America’s new landscape of class and conflict.

Simply the best book I’ve read for years. Communist geography and musings on the class struggle! Here often writes for the Brooklyn Rail here https://brooklynrail.org/2024/6/field-notes

- Solidarity (a UK based group) published the articles/pamphlets As we see it (1967) and As we don’t see it (1972) which are excellent short introductions to these kinds of politics and organising ideas.

- Vincent Bevins (2023) If we burn: the mass protest decade and the missing revolution.

Why do protests and uprisings fail? Why do they often end up actually worsening the situation they were hoping to make better? Some good points on the historical development of activism, and some mostly flawed but interesting analysis of various global uprisings and their organisational forms.

- Vital Signs

https://www.vitalsignsmag.org/ An excellent example of what some militant healthcare workers are doing organising in that sector. Also have a look at the book Sick of it all! from PM Press here https://pmpress.org.uk/product/sick-of-it-all-work-inquiry-struggle-in-the-nhs/