The following thoughts were presented at an international meeting of comrades in September 2023

I want to address the gap between the discussion about the current ‘strike wave’ and the ‘contours of the world commune’. I will try to proceed from the role of a ‘program’ in the transition from strike wave to class movement, to the question of dual power during the peak of class movements to the question of revolutionary transition.

The challenge is to think about revolutionary transition neither in a sense of ‘gradually increasing degrees of organisation or consciousness of the class’, nor in a spontaneous sense of a movement that can voluntarily move in all directions. A movement has to be able to build on previous experiences or relationships and needs time to develop collective knowledge. A transition is materially determined by the time and structures it takes to change the divisions of, amongst many others, manual and intellectual labour or different stages of regional development.

It will need a collective political debate and research to determine to what extent existing organisations or campaigns are part of the necessary ‘school of the class’ to build both collective knowledge and social cohesion, such as trade unions, cooperatives, experiences of self-management etc. and at what point they become confinements and castles in the sky due to the structural limits of laws and markets. We will have to determine what kind of structures remain from the ups and downs of strikes and movements that play a positive role in the sense of preserving a certain class wisdom or social connections that were created by the movement, without turning a blind eye to the necessary stagnation and re-integration of most ‘struggle organisations’ once the struggle is over.

The role of a ‘class program’ during the transition from strikes to class movement

Our old ultra-left wisdom maintained that putting forward ‘general demands’ runs the risk of curbing the spontaneous dynamics of a situation of strikes like a blanket and that it should rather be the strongest strikes that should set a point of orientation for others. The wisdom stated further that rather than focusing on demands that have to be recognised and fulfilled by the bosses and their state, we should instead promote direct forms of reappropriation, e.g. that workers should reduce the rent they pay or squat houses rather than demand a rent cap. There are merits to this old wisdom, in particular when we see how the wider left tries to use ‘general demands’ to unite a strike situation from the outside, without actually analysing the strikes in detail and their advanced and backward tendencies. Still, we also see that in situations of concrete movements, the old wisdom might confine us to a sphere of de-politicised immediacy that only looks for the ‘most radical’ points and is silent when it comes to the movement as a whole.

During the recent ‘strike wave’ in the UK, the trade union initiative, ‘Enough is Enough’ proposed a joint platform of demands that included an energy bill cap, amongst others. In general it seemed a step in the right direction to create a united focus of the various strikes and to address issues that go beyond the sphere of the immediate wage. The problem of the ‘strike platform’ was that is came from the top of the union hierarchy, that various unions and political forces tried to compete within the power vacuum that Labour has left and, most importantly, that it remained detached from the concrete strike demands – it did not question the law which prohibits ‘political strikes’.

During the Gillet Jaunes mobilisation in France, we saw how the focus on ‘taxes’ created overlaps between proletarian and petty bourgeois tendencies. It is obviously necessary to look in detail at how this overlap expressed itself in concrete forms of struggle, but to push for working class demands, such as the increase of the minimum wage or an end to temp contracts might have created stronger bonds with the wider class. The same could be said for the recent movement against the pension reform, where young and precarious workers fought without their own interests being reflected in the goal of the movement.

The transitional program of the Fourth International, 1938

According to our old wisdom, we criticised the ‘transitional program’ as a kind of manipulative trick of leftist wannabe leaders, who wanted to raise the consciousness of workers by promoting demands that seem common sense and realistic, but that capitalism won’t be willing or able to fulfill, thereby opening the eyes of the working class for the need of revolutionary change. This criticism is valid if we look at how the various Trotskyist groups have referred to the program as some kind of eternal recipe.

Re-reading the transitional program of the Fourth International as a concrete intervention in a concrete moment of time and against the background of our current moment today, I was astonished at its strategic boldness. It refers to a concrete moment, in terms of a global pre-war situation of imperialist tension with high inflation and increasing unemployment, where the old leadership in the form of left parties and trade union leadership have lost relevance and the class is developing new forms of militancy, e.g. in the form of the sit-down strikes. At this moment in time, the program draws a few concrete lines of working class defense in the sand by proposing to fight for automatic inflation compensation to defend wages, working time reduction and public and transparent recruitment processes to defend against unemployment. We can discuss the wider proposals, such as nationalisation of certain industries and the banking system, but in general the demands are not formulated as a legalistic offer of dialogue with the state. At the same time, the demands are attached to concrete proposals of how to organise the necessary power to enforce them, e.g. in the form of workplace committees and workers’ militias. It is true that the program remains general and largely admits that revolution was not on the immediate cards and that the class would have to gather its forces through a defensive battle, but perhaps that is part of its strength.

We have to discuss if the program of 1938 can still serve as a reference point when trying to formulate our own responses in concrete moments, e.g. for a ‘working class program’ during the pandemic, which both addresses immediate workers’ interests and attacks the nexus of a privatised and state-bureaucratic healthcare system. I hope that a re-reading of the program can serve as a productive provocation of our old wisdom. At the same time, the program of 1938 certainly leaves various doors open for the general opportunism of official Trotskyism, e.g. when it comes to the trade unions, to the question of ‘oppressed nations’, or alliances with the peasantry. More recently, comrades such as Loren Goldner or Karl-Heinz Roth have tried to formulate ‘transitional programs’ for the current times; we have to reflect on their use value together. [1]

The Transitional Program (Part 1) (marxists.org)

The question of ‘non-reformist reforms’

We have to distinguish the transitional program from the strategy of ‘non-reformist reforms’. Both address the challenge of the class having to gather its forces, to develop strategic capabilities and to learn how to rule, though while the transitional program is largely an imposition, the concept of ‘non-reformist reforms’ focuses more directly on how the class can influence the management of capitalist society to create certain plateaus for its own interest and power.

In the 1960s, Andre Gorz proposed that through the use of “non-reformist reforms,” social movements could both make immediate gains and build strength for a wider struggle, eventually culminating in revolutionary change: “through long-term and conscious action, which starts with the gradual application of a coherent program of reforms.” Fights for these reforms would serve as “trials of strength.” Small wins would allow movements to build power and put them on more favorable footing for the future. “In this way,” Gorz argued, “the struggle will advance. . . [as] each battle reinforces the positions of strength, the weapons, and also the reasons that workers have for repelling the attacks of the conservative forces.” It is not by chance that later on he would write a farewell to the working class as his reforms referred primarily to ‘social movements’ and ‘social demands’.

Today the idea of ‘non-reformist reforms’ is en vogue again and we see its contradictory nature. On one hand we see a positive politicisation of the debate and the return of strategic thinking: what kind of proposed changes can connect our immediate strength with a longer-term goal? We could discuss, for example, the current campaigns for a ‘socialisation’ of large scale property owners in Berlin. The campaign has politicised a wider debate, which spread from the question of housing to the question of industries and ‘green transition’, and put a ‘general interest’ and ‘democratic control’ back on the agenda. At the same time, the campaign remains dependent on ‘campaign forms’, detached from working class power, and embroiled in legalistic dialogue about the actual implementation. We see perhaps the opposite problem with ‘abolitionism’ in the US, which primarily addresses the need for changes in the prison and police regime, without addressing the wider issue of poverty and workers’ control necessary to undermine the ‘crime regime’ of the state. At its most acute moment, we can still maintain that Syriza expresses the fatal dead-end of the attempt to establish a dialectic between movement and capitalist institutions, while this should not prevent us from looking at and engaging with concrete campaigns.

André Gorz’s Non-Reformist Reforms Show How We Can Transform the World Today (jacobin.com)

The question of dual power and its limits

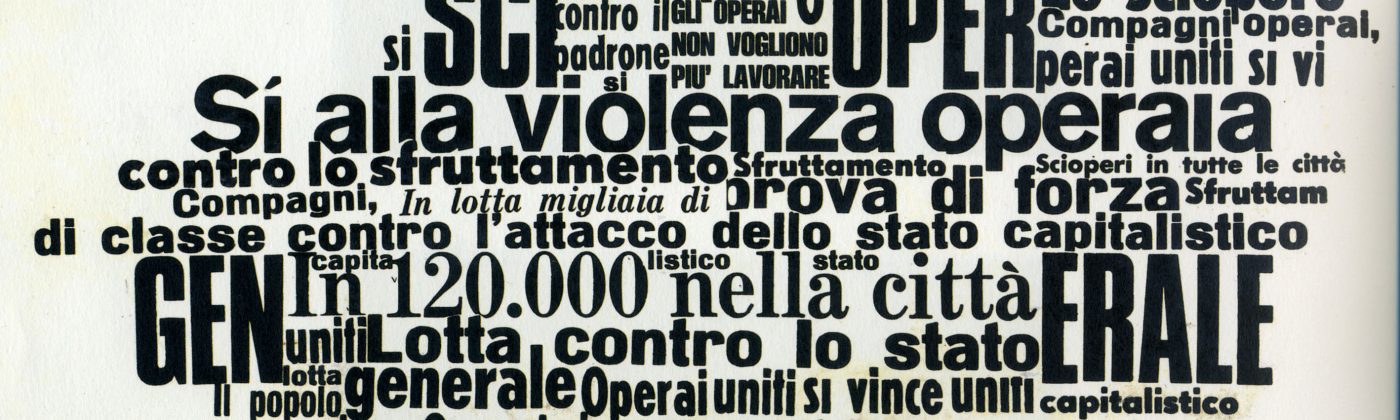

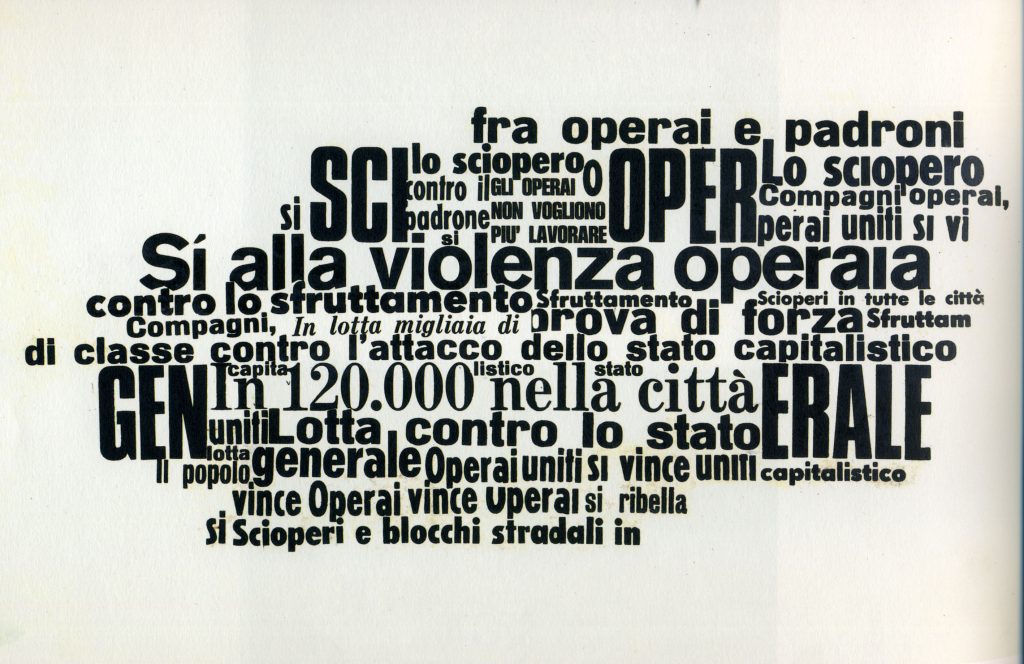

The debate around the concept of dual power originated primarily in the 1905 revolution, where the idea that councils could grow as economic, political and military bases and at a certain point tip the balance of power. Later on, in Italy in the 1970s, groups like the Political Committees for Workers’ Power around the newspaper Senza Tregua revived the concepts with their own strategy of ‘workers’ decrees’. During this moment of heightened class struggle, various strategies of generalisation emerged within the radical left. Lotta Continua and others decided, also against the backdrop of the military coup in Chile 1973, that an electoral victory of the PCI, pushed by a workers’ program from below, could generalise and defend the movement – it failed even at the electoral hurdle. Other groups of the autonomia focused on a workers’ campaign for a concrete set of demands, which included a general rise of the minimum wage, reduction of working hours and a general guaranteed income for students, unemployed and people working unpaid at home. While supportive of the latter, Senza Tregua emphasised the primary need for ‘workers’ decrees’ as concrete impositions: bringing sacked work-mates back into the factory against the will of the employer; housing occupations and ‘proletarian shopping’; direct attacks on fascists and company security; local ‘taxation’ of the bourgeoisie in the form of reappropriation of wealth. In Rome the workers’ committee at the polyclinic imposed free clinics and an actual change in the law that took away the power from the semi-mafia, semi-fascist ‘barons’ of the clinic hierarchy – perhaps a ‘non-reformist reform’ in a proletarian sense. Senza Tregua framed this as a strategy of growing dual power as a phase of transition, whereby the growing was primarily conceived as a territorial expansion that would eventually culminate in a civil war situation.

In hindsight we can see that these concepts of transition and of what a revolutionary moment would look like were fairly old school and perhaps lagging behind the actual revolutionary practice of the movement. The movement constituted itself not only as a force to impose decrees and not only as a force that would slowly undermine the control of capital and the state over universities, workplaces or working class neighbourhoods. The movement also constituted itself as a productive power, through the generalisation of knowledge within its own practice, e.g. in assemblies of workers and students, or doctors and porters or assembly line workers and technicians. Producing the movement itself, its practical structures, its media, its critique of management and to a certain degree official science (critique of mainstream medicine, nuclear power etc.) was a potentially transitional act, necessary to positively supersede the ‘dual power impasse’ that the movement was facing.

Unfortunately, this ‘productive element’ of the movement was only theorised as ‘self-valorisation’, a concept that shied away from both the question of state power and from large-scale workers’ control over the main essential industries. Therefore, the Italian concept of ‘revolutionary transition’ experienced a fatal bifurcation.

On one side, there was the idea that ‘the class imposes the management of affairs on capital’ while undermining its power in concrete terms and appropriating wealth; after overestimating the political scope of ‘wage struggles’ during 1969, this was a kind of hippie-ish or termite-like understanding that would avoid the winter palais moment of unifocal confrontation and focus on changes of the actual relationships and generation of counter-knowledge. It had a certain appeal to see what was happening, e.g. the widespread questioning of authority and professionalism, as a ‘revolution’ in modern capitalism, but this ‘strategy’ was slowly undermined by restructuring, cultural isolation and the use of the capitalist crisis.

On the other side was the primarily ‘negative’ concept of expanding workers’ decrees and ‘refusal’ territorially and destroying the capitalist state, without a clearer strategy and vision for a productive takeover. Without such a vision, the strikes started to run empty, the calls for a ‘return to normality’ became louder also from within the class, to which this concept of transition could only react with military escalation – most of Senza Tregua ended up in armed groups such as Prima Linea. The question of the role of a centralised class force during the transition was answered only in a traditional political sense in the form of the ‘proletarian dictatorship’ of the most organised elements of the class to defeat the class enemy – but not in relation to the role of such a central force in the process of undermining the material barriers for social participation, e.g. through the socialisation of knowledge, the end of the isolation of the household and so on. These barriers won’t all be brought down through a revolutionary upheaval itself, which explains and justifies the role of a centralised and politicised force during the transition that has to make itself redundant as much as possible in the course of it.

There is a return of the concept of ‘dual power’ today, with fairly large conferences in the US and debates within the libertarian milieu, though it seems that ‘dual power’ has degenerated into a general mish-mash of any kind of ‘rank-and-file’ organisations that also take care of material needs of the class, such as tenant unions, cooperatives or rank-and-file unions, plus, of course, Rojava – without any major strategy apart from ‘expansion’.

Dual Power: A Strategy To Build Socialism In Our Time (dsa-lsc.org)

Post Gathering Retrospective | Dual Power 2022

The moment today

The widely acknowledged necessity of some sort of ‘green transition’ has opened some doors, and the advanced parts of the movement are going beyond the limits of ‘green technical expertise’ that just looks for alliances – workers being one possible ally amongst many others. At the same time, we see how green liberalism is the spearhead not only of neoliberal green austerity that calls for an attack on working class consumption levels, but also of re-militarisation for a green democracy.

In this moment, struggles like at GKN in Italy have an organic vanguard position, starting from the solid grounds of working class self-organisation and technical productive knowledge, but reaching out actively and practically to the wider critical science, the green movement, campaigns for free public transport and to the precarious parts of the class with a concrete ‘green’ class program, that aims at forcing the state to finance a worker-led transition. Of course this struggle might well end up limited to running a crowdfunded bike part factory, but the wider aspiration that was formulated and practically fought for is of importance.

Both the pandemic and the climate crisis have demonstrated that a working class-led transition or alternative plan to the incapability of capital and state cannot be some kind of bricolage of half-knowledge generated in social centres or isolated occupied factores. The thorny issue of the relation between expert knowledge, the science workers and the wider working class is currently under theorised and only touched upon practically on the lower-skilled fringes, e.g. amongst so-called tech-workers.

At the same time, the increasing militarisation, concentration of wealth/power, deepening of the crisis and lumpenisation of the bourgeoisie are showing us that the transition won’t happen by convincing ‘society’ with a technically sound alternative – the necessity of mass militancy to enforce a working class plan is more pressing than ever.

It will primarily be the role of workers in the essential industries to enforce, as a medium step, the end of bullshit service jobs and unnecessary polluting industries through ‘worker decrees’ and the redeployment and retraining of the liberated workforce under worker control and drastically reduced working times. The degree of social chaos and disorganisation amongst the class may not allow for such a ‘productive combination’ of working class intelligence and dual power as an intermediate and relatively controlled phase of transition – but it would be a best case scenario.

Lasst uns aufstehen! – Das Fabrikkollektiv GKN | labournet.tv

Some possible tasks

It is significant to discuss what historical role ‘programs actually played’, from the Gotha to the Manifesto to the various programs of revolutionary syndicalism, and what kind of role a program could play today.

I think it would be fruitful to revisit the ‘Italian experience’ of the 1970s from a programmatic point of view, as it was the high-point of class struggle in recent times, but has primarily been analysed regarding levels of self-organisation of the class, less regarding its programmatic efforts and concept of revolution.

We could proceed by reflecting on our own stage of debate and re-read, amongst other things, ‘the Contours’ and ‘Insurrection and Production’ for blind spots when it comes to intermediate programs.

We could then look in more detail at the various current ‘programs’ from municipalism, to ‘European minimum rights’ to green transition to debates about dual power and formulate a productive critique.

We could engage in a basic empirical analysis of the employment share between essential labour and socially/naturally unnecessary labour in Europe and the main working class composition within the essential sector and its global dependence.

We could finally look at the situation of concrete current struggles and working class organisational initiatives in Europe, their most advanced tendencies and their various impasses. Here, the balance sheets produced by comrades who experienced actual movements, such as in France, will have a central significance.

We could try to synthesise a type of manifesto from this, a ‘balance sheet of the strike wave’ that anticipates a wider future program. We could use it for wider propaganda with concrete organisational proposals, e.g. an invitation and structure to collectivise ‘struggle analysis’, and as an introduction to our circle.

All this could easily be a lifetime engagement and fill books, but perhaps it would be possible to constrict ourselves to a work-plan of six months and a pamphlet of 30 pages.

We could primarily address the vast amount of grassroot initiatives that aim at ‘working class organisation’ and are interested in a wider debate, but that lack a political compass and umbrella.

It could also be a test if we can work together as a wider structure and clarify differences and shared views.

——-

Footnotes:

[1]

“As a first approximation, it means the global program which can unify, as a “class-for-itself”—a class prepared to take over the world and reorganize it in a completely new way—the wage-labor forces currently dispersed in the (somewhat diminished but still central) classic “blue collar” proletariat, the dispersed and casualized sub-proletariat, and those elements of the technical, scientific, intellectual and cultural strata susceptible to allying with such forces. These are, in “inverted” form, the forces actually comprising what Marx called the “total worker” (Gesamtarbeiter).”

What follows in conclusion, then, is a program for the “first hundred days” of a successful proletarian revolution in key countries, and hopefully throughout the world in short order. It is intended to illustrate the potential for a rapid dismantling of “value” production in Marx’s sense. It is of course merely a probe, open to discussion and critique:

- implementation of a program of technology export to equalize upward the Third World.

- creation of a minimum threshold of world income.

- dismantling of the oil-auto-steel complex, shifting to mass transport and trains.

- abolish the bloated sector of the military; police; state bureaucracy; corporate bureaucracy; prisons; FIRE; (finance- insurance- real estate); security guards; intelligence services; cashiers and toll takers.

- taking the huge mass of labor power freed by this to radically shortening of the work week

- crash programs around alternative energy: (in the long run, if possible) nuclear fusion power, solar, wind, etc.

- application of the “more is less” principle to as much as possible (examples: satellite phones supersede land-line technology in the Third World, cheap CDs supersede expensive stereo systems, etc.).

- a concerted world agrarian program aimed at using food resources of North America and Europe and developing Third World agriculture.

- integration of industrial and agricultural production, and the breakup of megalopolitan concentration of population. This implies the abolition of suburbia and exurbia, and radical transformation of cities. The implications of this for energy consumption are profound.

- automation of all drudgery that can be automated.

- generalization of access to computers and education for full global and regional planning by the associated producers

- free health and dental care.

- integration of education with production and reproduction.

- the shift of R&D currently connected with the unproductive sector into productive use

- the great increase in productivity of labor will as make as many basic goods free as quickly as possible, thereby freeing all workers involved in collecting money and accounting for it.

- a global shortening of the work week.

- centralization of everything that must be centralized (e.g use of world resources) and decentralization of everything that can be decentralized (e.g control of the labor process within the general framework)

- measures to deal with the atmosphere, most importantly the phasing out of fossil fuel use by 3 and 6