A comrade from Mumbai sent us this report on recent riots in India. Italy, India, the youth is getting restless…

An intense stand-off erupted between unemployed youth and the government forces recently in Patna, capital of the state of Bihar. The intensity of the clashes makes it unique, as there have not been many clashes of this scale in urban centres of India in recent decades; but the dynamics behind it are in no way new or isolated. This essay will try to open up these complex dynamics behnnd government organised recruitment exams and what they mean in a context like India’s.

The Railway Recruitment Board (RRB) conducts the exam every few years to enroll new employees into the railways (this is exclusive of many contracted positions such as caterers, sanitation, etc.). Specifically, these exams were for the Non-Technical Popular Category (NTPC) Group D, which is meant for recruitment of the helpers and manual working employees. The last recruitment based on RRB-NTPC exams was done in 2018, when more than 36,000 candidates were recruited out of 12 million applicants (as per their own website). This showed a discrepancy, as before the exam the RRB had announced a total of 100,000+ vacancies. This time, the notifications for the exam and recruitment have been appearing since 2019, but the exams were delayed citing Covid till 2021. Again, over 12 million applicants gave their name. Students gave the first rounds of written exams between December 2020 and July 2021, out of which 700,000+ students were declared eligible for round 2. This announcement came 15th January, 2022. Once recruited, the candidate would have become a government employee with a fixed job and a pay scale that starts at double the salary of an average contract worker.

After the results were announced, the board changed rules the last minute for Group D because of which 12 million applicants would have had to appear for more exams within 2 days. Further, many of the Group D applicants argued that the more highly educated workers had also qualified at their level, which left an uneven ground. It seems that once again, the Railways is reluctant to recruit. This is understandable, as there is a massive disinvestment underway in railways too, as well as the poor fiscal health of the world economy.

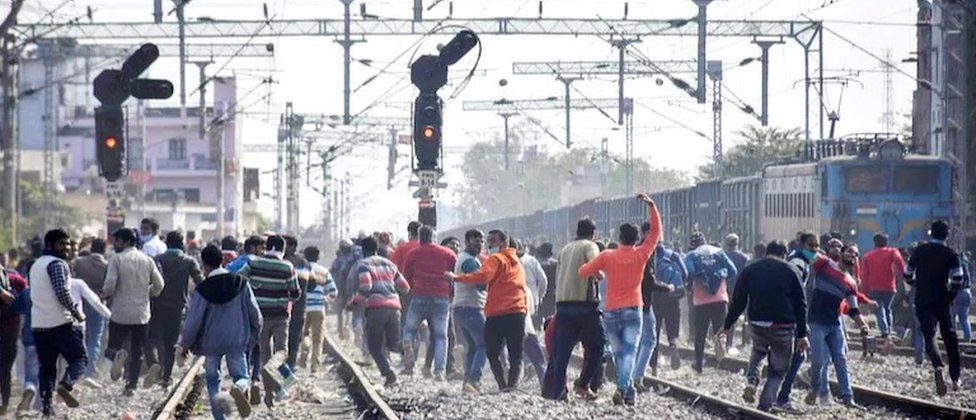

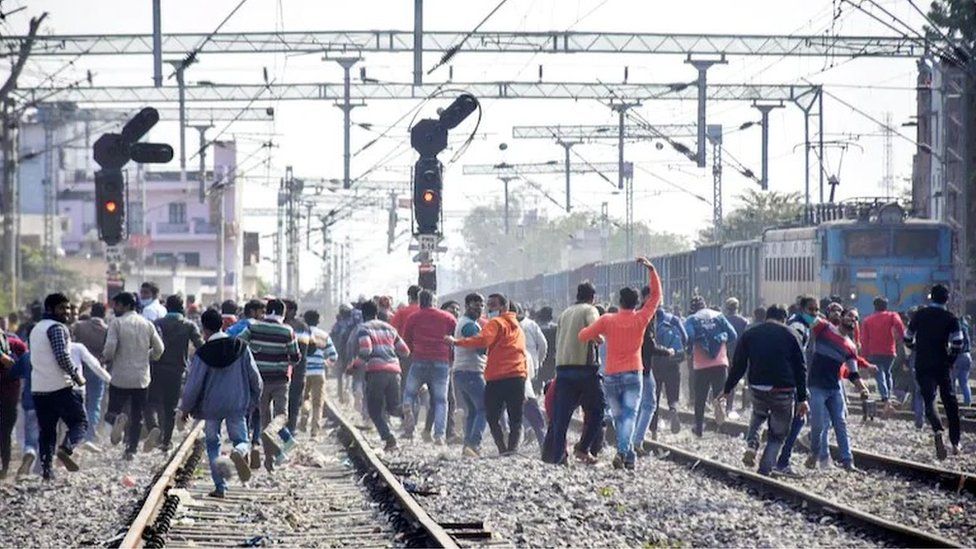

But protests started erupting from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, and candidates alleged some irregularities in the procedure. These two states account for the bulk of the applicants for these exams. These two states are also among the labour basket of India. The protests did not draw much attention as they began with “peaceful” gatherings at railway stations. Once the mass became critical, police tried dispersing them, and clashes began. It was an organised attack-counter attack between police and unemployed youth, and it led to trains being burned at a number of places. Elections are near in Uttar Pradesh, so the agitation intensified even more with opposition ruling class parties chipping in. Citing the anarchy and violence, the railway board suspended the exams altogether and has set up a committee for investigation of the problem, which assures to bring out an amicable solution by mid February. In their circular they noted “Such misguided activities are highest level of indiscipline rendering such aspirants unsuitable for Railway/Government job. Videos of such activities will be examined…and candidates/aspirants found indulged in unlawful activities will be liable for police action as well as lifetime debarment from obtaining Railway job.”

The protests have continued to gather more students. It sheds light upon how massive the coaching economy to train candidates for these exams is in the middle of the precarious conditions. There has been a presence of coaching class teachers and staff at the protests, and in the aftermath, the police has leveled charges of instigation against a coaching class head popularly known as Khan Sir. Khan Sir created success with the Youtube-to-Business outreach model for coaching students for public exams, and has classes all over northern India now. There are many more big and small coaching centres in towns. The students often flock from the neighbouring villages to the towns and cities where coaching classes flourish. It was seen during the 2019 UPSC protests in New Delhi also that coaching classes are places where candidates organise in case of any irregularity. Needless to say, along with the coaching economy, there is a rentier economy too that flourishes in these cities, and that also contributes to the mass character of the candidates, who often live in close vicinity.

Another factor to be considered is that over the last few years – especially after lockdowns – the mode of coaching is increasingly shifting to an online one where companies like Whitehat, Akash-Byjus, Udemy, etc. are eating into the share of the smaller coaching centres around. This could account for how active and concerned coaching classes are about these irregularities and how they come to become directly involved in protests whenever an anarchic situation arises. The existing economic arrangement seems to undergoing a lot of pressure. In the recent doctors’ strike that took place in New Delhi, it was not only coaching classes, but also resident doctors themselves who were demanding that process for doctor recruitment be continued without any hindrance, while it was the organisers of the exams (a govt. run body) which was stalling.

This anarchy no doubt stems from the changes in global capitalist relations. On the one hand, there is a vast population of skilled labour force which saturates government recruitment exams very disproportionately. This is an aspirational class for whom the government job seems like the most accessible route to a secure middle class life. The recession has sealed the bottleneck of these jobs. Further, there is a move towards disinvestment and a general change in labour relations. Those in power wish to extend the already dominant temporary work regime, and are antagonising the class entrenched in the older labour situation. Banks, teachers, state and union services, medicine, defense, airlines, telecom – every now and then protests arise against the manner in which the government is not following its own protocols!

This also shows that the so-called private sector does not really have a different plan to reorganise each and every sector which it is inheriting from the government (far from having plans for sectors which have not yet been touched). The Indian state, though its subsidiary enterprises, continues to be the de facto organiser of much of the general services which are crucial to the functioning of the economy, and this situation does not seem to change anytime soon, given the lack of any strong alternative. The situation is further deterred by increasing austerity.

The highly surplus nature of the working class along with a deepening recession shows the extent of anarchy in the functioning of everyday life. There is a pressure from the skilled, educated workforce to keep the status quo running, even when the managerial apparatus is unable to do so. There is nothing new about these irregularities and clashes over recruitments; what is new, however, is the increased precarity which the pandemic has brought about and how it has pushed a large number of the workforce towards the brink. These eruptions are only likely to increase in the coming future.