(Written in 1998, translated from: Wildcat Zirkular no.62 )

We translated this older article for a critical reflection of a talk by Michael Heinrich. Comments welcome…

In the 1990s, a critique of capitalism spread throughout the German political left, which calls itself ‘value-critical’ and claims to be the most radical critique of current social conditions. After Seattle, Prague, etc., more people today are again concerned with a radical critique of society as a whole. In their search for theoretical tools, the first thing they come across in this country is this ‘value critique.’ But it leads to a dead end, because it itself remains trapped in the mystifications of the ‘market economy’ or the ‘commodity society’ that have been successfully re-established by the ideology of neoliberalism over the last twenty years. When neoliberalism extols the market and the transformation of everything into commodities as a remedy, ‘value critique’ merely turns this argument around and thinks that with the critique of the commodity it has already done away with capitalism – a fate it shares with the Situationists’ critique of the commodity, which has also been attracting renewed interest in recent years. Above all, however, the ‘value critique’ is a practical dead end, because its theoretical critique remains meaningless for what we do and how we live. It can be limited to being a radical ‘attitude’ or ‘posture.’

‘Value critique’ was first advocated by individual groups such as ‘krisis’ or ISF (Freiburg), but it can now be found as a claim or jargon in many publications and has become a kind of ticket for ‘being radical.’ Its theoretical core consists in the fact that the commodity character of products and their value are placed at the center of critique. This is a departure from ‘workers’/labour movement Marxism’ (the old socialist and communist parties and trade unions), which has turned Marxism into a theory of the struggle for distribution between the opposing interests of the working class and capital. Here, ‘value’ is considered the basis of the social structure (‘the socialisation of and through value [Wertvergesellschaftung]’), while the class character of society is treated as a mere phenomenon of competition within the logic of the market.

Ironically and polemically, we call this thinking, ‘New German Value Critique’ [Neue Deutsche Wertkritik] (NDWK), which alludes to Marx’s ‘German Ideology’, in which he polemicised against an idealistic ‘critical critique’ typical of left-wing intellectuals in Germany during his time. In this lies a parallel to today’s ‘value critique’ in Germany, whose concept of ‘critique’ has always been detached from existing circumstances and, as ‘critical critique’, only pleases itself. It imagines itself to be outside the conditions most people actually face and, for this very reason, remains trapped in the false ideas that this society produces.

In the following, we do not want to deal with this or that particular variant of ‘value critique’, but to show why this ‘value critique’ is not a critique of value, does not overcome the errors of ‘workers’ movement Marxism’, but only repeats them, albeit from a different standpoint. This is not about any particular theorems of ‘value critique,’ but about mystifications of the kind that accompany capitalism every day.

The totality of capitalism initially presents itself in such a way that all things and relations become commodities – and this already offers us enough cause for criticising and hating these alienated social relations. But the commodity form itself does not explain to us why social relations are like this and where the starting point of their overthrow can lie. The enigma of the commodity form consists precisely in the fact that it conceals the real connections and foundations of capitalism. It is a moment of alienation and, at the same time, a dense fog that obstructs the critique of relations and their overcoming. It is therefore no wonder that the ‘critique of value’ knows only two equally impractical ways out of this dilemma: either it leaves the overturning of relations to an objective law of economic collapse (crisis), or it indulges in cultural pessimism that denounces all practice as ‘wrong’.

The commodity form is not the whole of capitalist society and value is not the universal key to its critique. It is the wrong expression for a historically particular and contradictory way of social reproduction of life, and it can only be understood in the context of these historical forms, which are by no means eternal. Today, many of these particularities no longer strike us as weird, they do not jump to the eye, but have been trivialised into normalities. The following historical sketch is therefore not intended to present a ‘historical derivation’ of capitalism, but to outline the peculiarities of capitalism, which point to the connection between commodity form (value) and mode of production. This shows that something like ‘value’ as a category and as a real relation can only exist under the conditions of a mode of production, which is based on the opposition of the producers to their own conditions of production and the opposition to their own sociality – on relations which necessarily include the commodity form and which, at the same time, disappear behind it.

1. The historical formation of the concept of value

‘Value’ is not a particular concept of the left or of Marxists, but first of all a general category of thought in capitalist society. Although bourgeois economics has abandoned a special theory of value, it cannot do without this term in its descriptions (‘value creation,’ ‘value chains’ ‘value adjustment’ etc.). The discussions about value and the formation of a special science of ‘value phenomena’ in the form of the political economy have been taking place since about the beginning of the 18th century and reach their conclusion in the first half of the 19th century.

In these discussions a completely new opposition or contradiction increasingly comes into focus. In everyday language, ‘value’ was and is used both for a subjective appreciation in the sense of usefulness and for an objective attribution of an abstract, monetary value. The distinction between value and wealth, between exchange value and use value, between an abstract measure of value and the abundance of material wealth, gradually emerges during this period, with both sides constantly being confused. For they exist only together, in a contradictory unity: something that has a value expressed in money must also have some utility. The issues in dispute are, for example: which society or nation is richer, the one that produces a lot of goods, or the one that has a lot of money?

In the historical process, the two sides separate and eventually come into sharp opposition. At the beginning of the 19th century, the contrast emerges strikingly in the first industrial crises: people starve, not because too little food has been produced as in earlier agricultural crises, but because too much has been produced, which therefore no longer achieves the necessary value – as a price – on the market. Today we have become accustomed to this paradox of the capitalist crisis. At that time though, it was the striking expression of the fact that wealth could suddenly have two completely different meanings.

The concept of value, in its sharp distinction from use value, presupposes a historical process in which these two quantities have come into a real opposition with each other. Only then can this opposition be held and determined in the mind. Concepts like ‘value’ are socially valid, objective thought-forms – they do not simply contain a false conception of the world, but express real inversions. Once established, the concept of value can already be ‘discovered’ in the commodity as the elementary form of this social contradiction – however, this historical and practical process of separation is always presupposed and consciously-unconsciously thought along.

In everyday life and in the pragmatically oriented sciences, human practice disappears and with it the basis that allows us to form concepts one way or another in the first place. We don’t need to know why we can handle abstractions like ‘value’ or ‘work,’ we just do. Such abstractions become natural categories for us, we take them for granted. Critique means to return these natural categories to what they arise from: to human practice. It is a matter of showing their connection with what we do, instead of explaining our actions from these categories. When the New German Value Critique speaks of ‘socialisation of and through value [Wertvergesellschaftung]’ or ‘commodity subjects,’ it is not providing a critique of the categories, but rather reproducing their appearance of naturalness by explaining the real relations from these categories, rather than revealing how they are grounded in a particular human practice. Value is determination of wealth-but maddeningly in opposition to what wealth means directly to individuals, namely, the disposition of the pleasurable things of life and happiness. Value is an abstract wealth that can abstract from people’s misery and still masquerade as wealth. What are the historical peculiarities in the production and reproduction of our lives that make such a folly possible in the first place?

2. Capitalist mode of production and value

Commodities and money have been around much longer than capitalism, but it is only with the development of capitalism, to be more precise: industrial capitalism, that the concept of value moves to the center of discussions. This is already an indication that it cannot be sufficient to fix the category of value to commodity or money. On the contrary, abstractions such as exchange, commodity, or money abstract precisely from what the respective historical content of these categories is, that is, what the determining element of this abstraction is. We speak of money in the Middle Ages as well as of money today, but the practice behind it is completely different – and so is the respective money! Goods in pre-capitalist societies have an exchange value, but no value. There is no ‘law of value’ as a regulating principle of production, which, in turn, is determined by completely different relations.

The great process of change, from the beginning of the 18th to the middle of the 19th century in Europe and America, leads to the generalisation of the commodity form and to the formation of value. This is connected with three closely interlocked ‘revolutions’, which have their starting point in England: a commercial revolution at the beginning of the 18th century, which resulted in the failure of John Law’s banking experiment and in the bursting of the first great speculative bubble, the South Sea swindle in 1719/20; the English agricultural revolution from about 1700 to 1750; and the Industrial Revolution starting in 1770/80.

It is not a matter of any historical logic, there is no inevitability of the processes. It is what happened in a rather unique and partly mysterious constellation; it’s a matter of what people actually did. Today, we can see in it the historical preconditions of worldwide capitalism, but there is no causality or determinism that derives from it. This process has preconditions even further back in time, above all the formation of a world market since the 16th century – but none of these manifold preconditions can logically explain why, since the 19th century, starting from a singular process in England, it comes or should have come to the dominance and enforcement of capitalism. History consists of the fact that people go beyond the given, change themselves together with the circumstances – which, in turn, eludes the schematism of cause and effect.

Agricultural revolution: social wealth in food and poverty as proletariat.

Between 1700 and 1750, the introduction of new methods, technologies and varieties of crops in agriculture increased the productivity of agricultural labour in England to a degree that had not occurred in previous millennia. For the first time in human history, a situation arises in which 80% of the population is no longer engaged in the immediate production of its food, but is ‘set free’ for other forms of production. Above all, this release means that they are forcibly separated from their immediate conditions of production, the soil. The agrarian revolution comprises two complementary moments: the increase of yields by fundamentally new methods and tools, and the expulsion of a part of the producers from their land. Just as in the rest of Western Europe, the English peasants had to free themselves from serfdom. They were strong enough to defend this freedom, but they were too weak to retain ownership of the soil as a means of their subsistence. With the enclosures of communally owned land, they become proletarians – free but destitute. The wealth of increased agricultural production (England then becomes one of the largest exporters of grain in Europe) is alien to them.

Industrial Revolution: the power of dead labour

This separation from the means of production forms the basis of the Industrial Revolution, which means, above all, that productivity becomes increasingly dependent on past labour. For a society to build machines and factories means to withhold a considerable part of the total annual product from annual consumption, to ‘save it up’, as it were, in the hope of increasing production in the future. This also gives rise to a new and expanded form of division of labour: agriculture produces food and raw materials for industry and those who work in it; industry produces tools and implements for agriculture and, in turn, for the development of industry; and, above all, entirely new goods are produced, historically mainly cotton cloth and iron tools. While in agrarian societies, production for one’s own needs (subsistence) dominated, production for others now comes to the fore. From the beginning of capitalism individual production processes entered into a global dependency in a comprehensive system of division of labour. Production only now becomes social in the modern sense of the word, but this social character [Gesellschaftlichkeit] exists in a doubly contradictory form.

Money as an abstract expression of the social character of labour.

Labour becomes a totality of labours, all of which are connected and interdependent, but not in the sense of common or consciously cooperating labour. Instead, individual labour relates to other labour only through a division of labour and the general commercial exchange of the products. Because of this contradictory nature of the social character of production, its social character can be expressed only as an abstract general form [Allgemeinheit] – as money. Money becomes the immediate and necessary mode of existence of social labour and expresses the totality of this global division of labour. In this whole context, the respective labours acquire a double meaning: they are concretely useful labours and at the same time a mere part of this totality of labour, i.e., abstract human labour.

In this second capacity, labour is the basis of value. Even if money had existed for thousands of years, it is only with this multiplication of products, – and with the production of new needs and the dependence on these needs, and the whole reproduction of a global system of division of labour – that money becomes the expression of abstract labour, the expression of value. Money expresses both: the access to this potential and unlimited wealth, which has only become possible through this new mode of production (therein lies its fascination) – and the alienated, social and unsocial, isolated, separate character of this mode of production. Money, or the lack of it, represents at the same time the separation and exclusion from this wealth. Money does not cause social contradictions, but it is these contradictions that give money its seemingly supernatural power.

But how and in what form does production take place within this contradictory social relation based on the division of labour? The idyll of ‘simple commodity production’, in which individual producers exchange their products, has never existed as a social system. Where mass commodity production begins, it is always already based on the opposition of the producers as proletarians to their conditions of production. Legally [!], this opposition presents itself as ‘private property’ of the means of production on the one hand and as the figure of ‘free wage labourers’ on the other. This legal relation further evaporates into the abstract realm of the ‘free individual’ and their human rights, which expresses the liberation from relations of immediate and personal dependency that were previously connected to the access to land (e.g. through serfdom, being indentured). At the same time, this legal ‘free individual’ definition disguises our new objectified dependencies due to the separation from the new, industrial conditions of production. What this legal form signifies is that the social character of labour itself is contradictory. On the one hand, the fact that we generally depend on a (now global) totality of labour, on the other hand, that we’re not (yet) able to relate collectively and communally to this production process, i.e., to be dominated by one’s own production instead of dominating it.

Capital as a mode of existence of a contradictory form of socialisation

The second contradiction, which is related to the mode of production on which the generalisation of the commodity form is based, is the process by which value becomes independent from the labour it originates from. As value, abstract labour is already objectified [vergegenstaendlichte] labour. The special feature of the new mode of production, as it asserts itself with the Industrial Revolution, lies in the fact that this objectified labour does not simply represent consumable wealth, but itself becomes again, as machine and factory, the essential basis of the production of wealth and its increase. The original separation from the soil, which was always contested, thus develops into a much more drastic separation: namely, our separation as individual workers from the wider social existence and relations of labour, which is the source of enormously increased production of wealth. It is no longer the natural conditions of agricultural productivity from which we are separated, but it is ‘produced productive power’ and our own social context or existence that is hostile to us. Past labour flows into the reproduction of every society, but here, for the first time, past dead labour becomes the calculated factor of an accelerated increase in production. Dead labour, value, becomes the purpose and content of producing – capital. The content of producing is not simply value, but valorisation. Value, as expressed in money, is only a thing-like [dinghafte] fixation of this process of valorisation. Value cannot exist outside this constant processing of value, i.e., of valorisation.

Value as a special form of wealth, and which is opposed to the wealth of the good things of life, appears only where this process of turnover or transition [Umschlagsprozess] takes place. ‘Value’ presupposes the process of becoming independent and opposed to living labour; it thereby presupposes the antagonism of dead labour as capital vis a vis proletarians. And just as value exists only as capital, which presents itself alternately as money, commodity, or means of production, so abstract labour exists only under the conditions of exploitation, that is, of the subordination of labour to the valorisation of capital.

But labour as value is already objectified labour. And the fact that this objectified form of abstract labour appears as value presupposes a certain opposition between objectified and living labour, without which the category of value could not appear at all. Now it becomes clear why, in the course of the 18th century, material wealth enters into a contradiction with abstract, value-related [wertmaessiger], monetary wealth. This is because the relations and means of production as capital, as dead labour, become independent vis-à-vis the producers and oppose their own category of wealth, namely value, to material wealth. The measure of wealth is not the good life of the people, but the usefulness for this process of exploitation, to which everything is subordinated.

Capital as the reified expression of the class relation

Capital is therefore not a ‘thing’, but a relation, more precisely: a dynamic relation, the constant process of separation and antagonism between proletarians and conditions of production. This separateness presents itself as a factual, object-like relation, but it can only exist as a social antagonism, as a class relation. The capital relation presupposes the existence of a class of propertyless proletarians, just as, on the other hand, the detached, seemingly independent conditions of production cannot exist without the conscious will of the capitalists. With the New German Value Critique it has become fashionable to justify the insignificance of the class antagonism by saying that ‘class’ is merely a category ‘derived’ from general concepts such as value and capital and remains entirely within the essential dynamics of capital. Such thinking worships the fetishism of the commodity and of capital. This is a result of the social relations themselves. This fetishism can only express the real relations in a twisted form. In describing capital or valorisation as ‘automatic subjects’ or independent structures, this form of ‘critique’ reduces all the relations of people in the production of their lives to mere reflections of a transcendental thing. Instead we have to maintain that we could not even think about concepts like value or capital if the antagonism, the antagonism of the class relation, were not already assumed.

The New German Value Critics see the world through the neo-liberal lens of the ‘market economy’. When criticising the commodity form, they ignore the content of this form. What circulates in the commodity through exchange for money is not simply value, but essentially surplus value. As a general form of wealth, the commodity is a commodity which has been produced under capitalist conditions. Its production as well as its exchange are subordinated to valorisation. Commodity and money are only transformed forms of capital, which, through this circulation, not only reproduces, but increases its value. It’s precisely because the relation to social wealth is only established through the commodity form, that circulation presents itself as a sphere completely separate from production. The New German Value Critique criticises the ‘Marxism of the workers’ movement’ for considering circulation only quantitatively as a problem of distribution and emphasises its qualitative side with the commodity form. But both consider circulation in isolation and ignore the production process. With the commodity form and the exchange form of the relationship between capital and wage labour, the ‘value critique’ thinks that it has already said everything about production. This is reminiscent of the workings of bourgeois economics and its equilibrium models, in which the factory is a ‘black box’ in which the singular notions of the factors of production (‘capital’ and ‘labour’) unite in a mystical way for the benefit of the gross national product.

The factory as the reality of the determination of value [Wertbestimmung]

The generalisation of the commodity form is based on industrial production, in which the conditions of production confront the producers as dead labour, as value becoming independent, as value that has become independent. The socially determining form of this opposition is the factory, with its despotic command and the subordination of the individual workers to a machine complex. What is decisive for this revolution is not that the majority of labour becomes factory labour – which historically has never been the case – but that all other production becomes dependent on industrial factory production and incorporated into its system. Social labour here becomes quite palpably ‘abstract’ labour, and it is here that the determination of value as an expression of abstract human labour is first realized. Workers become indifferent to, and abhor concrete or particular labour, while the development of production is based on the constant change between various particular labours (or ‘jobs’), all of which are regarded only as being something different of the same, average labour (or ‘different day, same shit’). The factory is not based on particular concrete labour, but on labour par excellence.

The history of the factory is the history of the continuous subjection of the proletarians to the capital command and of the constant conflict over the extraction/extortion [Abpressung] of labour. It begins historically with the exploitation of women and children, because at first only they can be subjected to the working conditions of the factory by making use of the (patriarchal) social hierarchy – this is still true today for all new industries in the world, e.g. in Asia or Latin America.

While on the level of circulation, in the exchange of labour power for money (wages), the impression of justice and harmony can be created, within production the ‘consumption of labour power’ takes place: Transformation of labour power into labour, appropriation of foreign labour by capital, subordination to the detached/separated conditions of production. There is no justice and no harmony. This detachment [Abgetrenntheit] must be constantly reproduced, and the whole despotic, servile character of the production process, with all its constraints, regulations, disciplining, overseers and punishments, is the necessary mode of existence of this detachment. Machinery and technology, in their concrete form, are themselves methods and means of subjugation; the despotic character of the capital command is inscribed in their concrete form. The history of technology does not follow an abstract and neutral criterion of increasing productivity, but is always linked to its role as a technology of domination. It follows the principle of the fragmentation of labour for the purpose of its controllability.

Nevertheless, the factory command cannot be understood simply as a technique of disciplining; it moves and exists in an insoluble contradiction. The factory is not mere disciplining, but it must constantly develop the social character of labour, the all-round connection of labour, in order to fulfil the purpose of capital valorisation. With the same means by which it seeks to subjugate living labour, it thus constantly creates means that increase the destructive power of the working class in its opposition to the extraction/extortion of labour. Historically, this is not a linear process, but it proceeds in cycles of constant recomposition of the working class and its struggles. Accordingly, when people look at the contradictory unity of disciplining and workers’ power they tend to emphasise one side or the other, depending on the historical phase. To insist and emphasise in one’s theoretical and political practice that this unity of contradictory moments is still valid cannot replace the concrete investigation of their development, but without this critical conceptualisation the investigation will not get beyond empirical stocktaking.

3. Summary: The Appearance of the Market Economy

The general compulsion to buy, and thus the generalisation of the commodity form, do not emerge from ‘the commodity’ or the market form as such, but from the detachment and antagonism between the conditions of production and the producers. Their poverty or lack of property in principle forces them to sell their labour power in order to be able to reappropriate by purchase the food they themselves produce. The wage relation, as which this detachment presents itself, leads to the generalisation of the commodity relation – not vice versa. And in this generalisation the commodity is no longer simply commodity, it is merely the transformed form of capital. The essence of the commodity and the riddle of value can only be deciphered if the semblance of ‘simple commodity circulation’ is broken: everything that comes to the market today in terms of commodities is a transit form in the circulation of capital – and only in this circulation of capital does what we call value exist. The fact that exchange relations are determined by value results only from the fact that not simply commodities are exchanged, but commodities as products of capital. Their circulation serves the realisation of the surplus value embodied by them, which in turn appears, in relation to the capital advanced, as the rate of profit. Mediated through competition, in the exchange of commodities the unity of capital presents itself as the general or average rate of profit. Only in this reference of value to itself, in the unification of the rate of profit, lies the reason why commodities have to be exchanged in certain relations of value, and the fetishism of the commodity is completed.

In the category of value the relation between capital and class is always already contained. It is one of the characteristics of capitalist socialisation that this relation (between value and class) makes itself invisible through the forms (money, commodity, market etc.) in which it expresses itself. From the individual standpoint as a buyer, that is, from the average standpoint of a critical critic, the reference to the total labour of society appears first and foremost as commodity and market. Through the commodity form and its value form as price, it has become unrecognisable from which process they originate and on which relations the forms of commodity and price are based. The commodity form of the products thus constantly creates the image of a market economy or commodity society, in which our context appears to us as the sum of exchange relations between isolated individuals. It does not matter whether I think this is good or bad. A critical attitude towards the ‘market economy’ – to which the concept of ‘socialisation through and of value’ [Wertvergsellschaftung] only puts another label – confirms this false appearance and inevitably leads to illusions about how this social relation can be abolished.

Where does that leave Marx?

Any discussion about commodity, value or capital today is of course closely related to Marx’s critique of political economy. At first glance, the systematic structure of this critique in Capital seems to agree with the disciples of ‘Value Critique’, who think that they have already discovered the essence of value with the analysis of commodity society. For this is how it starts: the commodity is taken, a mysterious value is determined for it, which refers to its character as a product of labour, but which appears in value as a material property. And because this applies to the commodity par excellence, to which all people must relate, we are dealing here with a general human phenomenon of alienation and fetishisation of relations. Isn’t this much more radical than just lamenting the unjust distribution of the product between entrepreneurs and wage-earners? In this way the question is already wrongly posed. The ‘New German Value Critique’ constantly strives for the opposition between a bourgeois humanist philosophy of alienation (to which it relates itself) and the ideas of injustice of the social-democratic workers’ movement (in which the protagonists of the value critique recognise their own Marxism-Leninism of the 1970s and 1980s, and which they want to leave behind).

Marx’s goal in his critique is quite different: namely, to criticize and overcome both modes of reaction to capitalism as themselves still ideological and twisted expressions of the fundamental class relation. For him, anti-capitalist romanticism and trade-union fantasies of redistribution are only two sides of the false manifestations of capitalism.

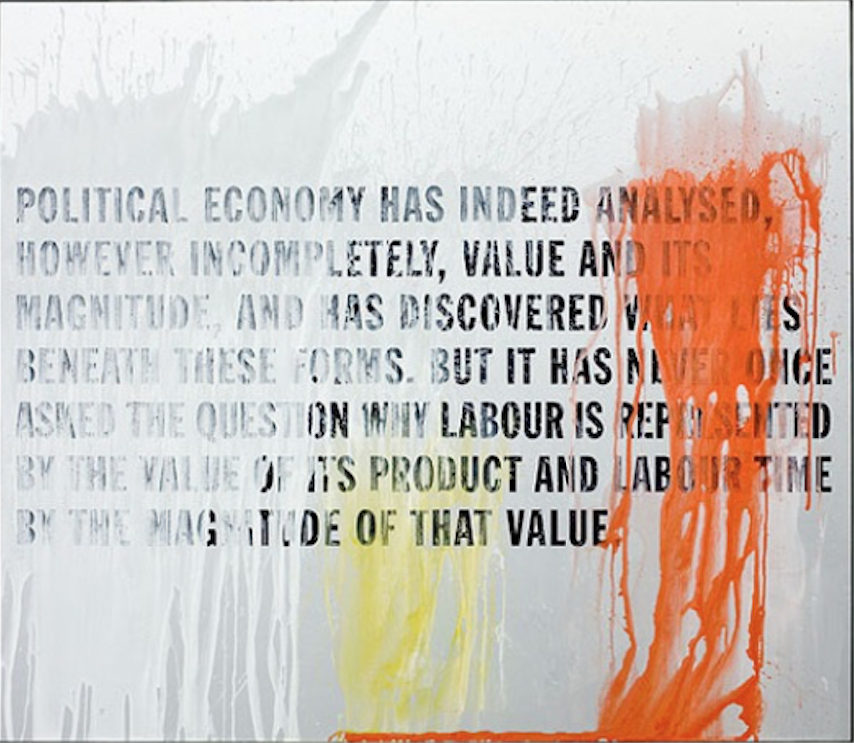

Methodologically, he proceeds in such a way that he takes the simplest and most elementary forms (categories) as a starting point and shows that they are false and untenable in themselves, that they are only the abstract expressions of underlying relations of production. The whole movement of commodities and money has no inner coherence in itself, but is only a facet of the movement of capital and the opposing relations of production enclosed in it. The ‘New German Value Critique’ overlooks precisely the critical nature of Marx’s mode of representation and thereby becomes ideology itself. Marx formulated more sharply when he criticised vulgar economics:

“We have seen that the conversion of money into capital can be divided into two independent processes, which belong to quite distinct spheres and exist in isolation from each other. The first process belongs to the sphere of the circulation of commodities and therefore takes place on the commodity market. It is the sale and purchase of labour capacity. The second process is the consumption of the labour capacity that has been purchased, or the production process itself. In the first process, the capitalist and the worker confront each other only as money and commodity owners, and their transaction, like all transactions between buyers and sellers, is an exchange of equivalents. In the second process, the worker appears pro tempore as a living component of capital itself, and the category of exchange is entirely excluded here, since the capitalist has appropriated for himself by purchase all the factors of the production process, material as well as personal, before the start of that process. But although the two processes exist alongside each other independently, they condition each other. The first introduces the second, and the second implements the first.

The first process, the sale and purchase of labour capacity, shows us the worker and the capitalist solely as seller and buyer of the commodity. What distinguishes the worker from other sellers of commodities is only the specific nature, the specific use value of the commodity he sells. But the particular use value of the commodities alters absolutely nothing in the determination of the economic form of the transaction, it does not alter the fact that the buyer represents money, and the seller a commodity. Hence in order to prove that the relation between the capitalist and the worker is nothing but a relation between commodity owners who exchange money and commodities with each other for their mutual advantage and by virtue of a free contract, it is sufficient to isolate the first process and keep holding onto its formal character. This simple conjuring trick is hardly witchcraft, but it forms the whole of vulgar political economy’s stock of wisdom.” (in ‘Results of the direct production process’)

F., Cologne