We hosted a discussion meeting with comrades who took part in the Wapping printer dispute. Below you can find the initial blurb, the recording of the meeting and a longer comment from a comrade about how class relations have changed since then.

*** Blurb

Wapping ’86: ‘Picket’ Bulletin and the New Technology Golem

* The defeat of the News International print workers is sometimes talked about as if the outcome was inevitable, due to new printing technology. Is this true? What does it tell us about automation and workers’ power thirty five years on?

* ‘Picket’ was an independent workers’ bulletin that ran to 43 issues during the dispute. It became a key source of information, by and for strikers and supporters. What made it successful early on, and why didn’t it become a focus for organising independently of – and when necessary against – the print unions? What does it take to produce a decent political strike bulletin today?

Two connected themes for a public meeting and discussion, opened by a printer who was involved in the picketing around News International’s Wapping operation, and in publishing ‘Picket’.

Related questions which could be explored:

• Was Wapping a strike, a lockout, an attempted occupation – or a combination of all three?

• How could the strike have ended differently, and what would that have taken? Could the workers have ‘won’? What did they think winning meant?

• News International pulled off a ‘bait-and-switch’ on its workers and the print unions, by which it provoked a strike on its own terms, while transferring production to the new Wapping factory without a hiccup. Did the workers really get taken by surprise? If so, why? • Before the dispute, Fleet Street print workers had a reputation as an ‘aristocracy of labour’ commanding fabulous pay and conditions, and wielding real day-to-day shop floor power. Is this true? Were potential allies put off by their exclusiveness, nepotism and pride in the job? To what extent did other workers and local working class people identify with and support the strike?

• Printworkers were organised into a complex network of well-resourced unions that used closed shops to leverage wages, conditions and access to jobs. How did the unions play to their striking members, and how did they help organise defeat? • What tactics did the strikers and pickets use, and how did they evaluate the effectiveness of those tactics?

• Are tech workers the new printers?

Background reading:

‘Picket’ issues 1-43. If you don’t have time to plough through, check the tone and content of some of the early issues and compare them with the late ones:

http://libcom.org/history/picket-bulletin-wapping-printers-strike-1986-1987

Short timeline of the dispute:

https://libcom.org/history/1986-1987-wapping-printers-strike

‘Paper Boys’ – personal account of the dispute written a year after it ended. The tone and views are fairly typical:

http://marx.libcom.org/history/paper-boys-one-man%E2%80%99s-account-picketing-wapping

*** Recording of the meeting

https://bit.ly/32joqM8

*** Comments after the meeting

I would like to continue the discussion that we opened in the Wapping meeting. A comrade has just posted an article about Heathrow workers fighting each other to save their own jobs. Do the events at Wapping in 1986 have any relevance to the present?

Before coming to the Wapping printers strike just a brief history ‘re-cap’ in very shorthand form.

The 1917 Russian revolution lead to many of the best working class militants around the world leaving the social democratic reformist parties and joining the new communist parties. The subsequent degeneration of the revolution and the communist parties (CPs) gave new life to the reformist parties and most of the communist parties themselves adopted the ‘parliamentary road to socialism’. A growing revolutionary consciousness in the working class was snuffed out.

In Europe at the end of WW2 capital had to rely on both the CPs and reformists to maintain social control but to make this possible welfarism and an acceptance of trade union representation were necessary. In the UK and most of Europe the post war period was marked by the welfare state, full employment and workers gaining rising living standards by regular battles over increased wages and shorter working hours.

My own understanding of the profitability of capital is not great but while this period saw a growth of industrialisation it also saw growing financial crisis with the US dollar – which had emerged from WW2 as the global dominant currency – forced to go off the gold standard in 1971, a real sign that at the heart of the world’s leading economy things were not going well.

In 1973 the UK coal miners began an overtime ban to gain a wage increase. After months of power cuts and a three day week in industry the Tory government of Heath called an election on the basis of ‘who rules the country’ – the miners or the government? Labour came in to pacify the working class while the assault on the union’s power continued to emerge. Thatcher won the leadership of the Tory party saying that Heath should not have taken on the miners without being prepared to see it through to victory. She spent many years, first in opposition and from 1979 as PM, preparing to defeat the miners and break the strength of the unions.

The main changes she made were preparations in the state forces for a war against the working class and legislation that made any kind of trade union solidarity action illegal not so much by jailing strikers but by bankrupting the trade union bureaucracy. Thatcher’s preparations for this war were motivated by the needs of capital to put an end to the post war settlement that had allowed the working class, via its unions, to push for improved conditions. And coupled with this (though again my knowledge is limited) was capital’s need for greater mobility – to be able to go anywhere in the world in search of profit, to pitch cheaper, unorganised labour in one part of the world against workers in the then industrialised countries.

End of historical background.

I worked in factories during this period and took part in the general ‘militancy’ of the 70’s. For example in 1973 I took home £50 a week as a skilled sheet metal worker. By 1983 I was earning £130 a week. Strikes, overtime bans etc were a regular occurance. Working class activity was not limited to actions over wages and conditions. When the first signs of the end of the post war settlement emerged the unions did take united actions. In 1972, when dockers were trying to defend their jobs and conditions against the new use of containerised shipping 5 dockers were jailed for ‘illegal’ picketing (new technology will appear again and again as a way of employers breaking their dependence on unionised labour) . In the aircraft factory where I worked the shop stewards planned a mass meeting to propose all out strike in support of the 5 dockers. Similar meetings were taking place across the country and there would have been a general strike by evening but the government backed down and freed the jailed men.

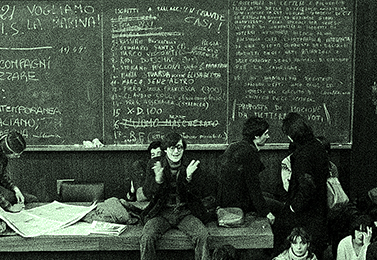

When the Labour government of the mid 70s tried to bring in laws curtailing the power of the unions it was stopped by a huge protest movement. (This widespread industrial militancy was matched by a radicalisation in every sphere of life – amongst students, in art, in sexual politics and remember this was not long after the huge anti-vietnam war protests and the 68 events in Paris)

However in the 70’s something new began to emerge – employers who would not bargain with the unions and who would get backing from other representatives of capital in a show of ‘class solidarity’. They were helped in this by the end of the period of full employment. The Grunwick strike of 1976 saw a small employer refuse to accept union recognition and getting political, legal and financial support from other bosses. The newspaper owner Eddie Shah did the same in 1983.

So, with growing unemployment a fact of life, Thatcher pushed the miners into their year long strike against pit closures in 1984. This saw both the escalation of working class militancy and also its inadequacies. Thatcher – on behalf of capital and with most of the personifications of capital backing her – had spent years preparing for a showdown, not just with the miners but via them with the whole working class. It was impossible to say this attack came out of the blue and yet the working class, within its trade unions and the union’s political party, Labour, had made zero preparations. On the contrary by 1984 most of the labour and union leaders were ready to tow the line, accept the new laws that more or less made working class solidarity impossible.

While Thatchers’ attack on the miners was clearly an attack on the entire trade union movement the miners were left to fight alone for a whole year. No-one from the miners union, including Scargill, called for solidarity action. Scargill, far more militant than the other union leaders, went into battle enthusiastically but clearly thought that it could be won in the same way that fights had been won over the previous 40 years.

In my own factory when I put down a resolution to call for the 8,000 London metal workers to come out on strike in support of the miners, union officials came along to argue that the miner’s didn’t want solidarity strike action as this would stop everyone donating to their strike fund. Of course what these officials were scared of was their union funds and offices being seized by the state which would happen if we had gone on solidarity strike which was now illegal. Overnight their salaries, cars etc would have vanished. So while the miners unsuccessfully battled daily with the state forces to try to stop coal movements the rest of the union movement carried on working, just chucking money in the strike fund which did nothing but prolong a hopeless battle.

Previously, in 1973, when the miners had fought the police for several days to try to shut down a coal depot they succeeded when thousands of engineering workers joined their lines and the police gave up. |But now, whipped into line by the new laws, other union bosses worked to prevent similar solidarity action and Scargill refused to challenge them or criticise the Trade Union Congress which refused to back the miners.

The TUC stood by doing nothing, the Labour Party disowned the strike and these bodies were held in such contempt by the mass of miners that they were unable to play their usual role in ending a strike. This time the job fell to the communist party. Kim Howells, a Welsh miners official and CP member (later a Labour MP) argued that the miners should return to work without a deal but with their banners ‘held high’. After a year on strike the miners went back and within a short time the industry had vanished.

The unions no longer had to be consulted by the bosses. At this time I worked in an artificial limb factory with a highly skilled and highly paid workforce. A new international conglomerate bought the factory and in a short space of time had developed new technology to make it possible to produce a limb by people who had received 16 weeks training not the five years that existing craftsmen and women had. It was obvious to some of us that a clash was coming but both the union and most of the workforce said ‘they can’t make limbs without us’. A couple of years down the line the factory was shut and production moved overseas. For six months the workforce picketed an empty factory. Who gave a toss?!!!

This was the background to the Wapping printers dispute, when Rupert Murdoch, owner of the Sun and The Times and other papers around the world, got rid of his Fleet Street printers – one of the most highly unionised group of workers in the country. Again there was no shortage of evidence about what the bosses were, preparing. I was in the Workers Revolutionary Party that had a daily paper printed by traditional methods employing skilled members of the print union. Gerry Healy, the party leader, secretly set up a new print shop, trained party members to use the new computer type setting equipment and others to do offset litho printing and then got rid of the old workforce saving the party thousands of pounds a week. If a two-bit sect leader could do it what was to stop an international tycoon?

Again, like Thatcher, Murdoch prepared for the war, setting up his own fleet of delivery lorries and constructing a new printshop outside of the traditional Fleet Street. He also brought the extreme right wing leader of the electricians union, Frank Chapel, into his plans, offering all the new jobs to his union. Again the workforce was totally outmanouvred and once again there was no significant solidarity action. The lorry drivers and the electricians crossed the picket lines – something that would have been unimaginable 15 years earlier.

So I am trying to describe the end of an era, the end of period of capital’s acceptance of trade union negotiations in any real positive sense. The space that capital had allowed for the reformist union leaders to strut the stage was shut down and their obedience to the state took priority. From there on unions became something that just tried to mitigate the attacks on their members. As they increasingly failed and as more and more production moved overseas, union membership plummeted and their ability to have any impact on the bosses plans became more or less zero.

At the time of these events, as I said, I was in the Trotskyist movement and so saw events through the lens of the Fourth International (FI). Since its creation in 1938 the FI had seen the working class globally as a militant force held back and ‘imprisoned’ by its reformist and stalinist leaders. In both the miners’ and printworkers’ disputes we had been very aware of the preparations of the state and the bosses and the changes within the realm of capital that was pushing them. However we saw the defeats only as the result of betrayals, of rotten leadership. The WRP had seen its role during these events as exposing this rotten leadership and, on paper, changing it. In reality all we did was try (and fail ) to recruit workers to our party who agreed with our analysis of the rotten leaders.

Looking back I think we need to look at what had actually happened to the working class itself during these post war years. Yes, the reformism of the Labour and union leaders did what it had always done, act as the agent of capital within the working class but what about the class itself? When the USSR collapsed I and others thought that this would open up the way for the soviet working class to make itself felt. What we all didn’t even begin to comprehend was what 70 years of brutal anti-working class dictatorship had done to the outlook and consciousness of the soviet workers. I think we made the same mistake in the UK and Europe. What had 40 years of reformism, welfarism and a cascade of commodities done to the outlook of the working class?

In the post war period it appeared that reformism and union militancy worked. Things just slowly got better. The union militancy of the printers, for example, led to conditions and wages no worker could ever have dreamt about in previous eras. Yet this was a militancy that had less and less to do with a fundamental change in society and less and less to do with the class as a whole. In the union movement politics was left to the Labour Party, all talk of socialism was strictly for sunday picnics.

While 40 years of union actions did see more and more commodities being stacked up in workers’ homes it hid an ever growing political complacency and a ever growing fragmentation of the class. For example in Rolls Royce where I worked the panel beaters, the most skilled people, had a premium on their hourly rate compared to other metal workers. To them, keeping this differential was more important than the unity of all workers in the factory. When there were outbursts of large parts of the class, like the protests against Labour’s anti-union laws, this was the dying gasps of a movement trying to retain the status quo and particularly the union bosses trying to hold on to their bargaining powers at the bosses tables. In no way was there any reflection on whether the way union militancy had worked would continue to work.

In our zoom meeting the question was asked if any links were made between the striking printers and the inner city youth who had rioted against Thatcher’s mass unemployment. But these were two different planets. There had been demonstrations in London by black people calling for a boycott of the Sun for its constant racism. For example in 1981, a story that mirrored the Sun’s treatment of the Hillsborough football fire, the Sun alleged that a house fire at a party in Deptford in which 13 young black people were killed was started by people at the party itself. The Sun printers and typeographers were printing this and an almost daily diet of racist shit. I’m not saying this in any ‘shock horror, what awful people’ kind of way but simply to say this is how things were. Again when the inner city riots of the early 80s took place the Sun churned out racist filth.

On one planet was the highly paid, job for life printers and on another the unemployed black youth – one of the parts of society that had never been included in the ‘everything slowly gets better’ . This didn’t rule out them coming together in changed circumstances but you have to acknowledge the existence of these two planets at that time. Neither group would have had the slightest concept of the other as a potential ally, rather as alien beings. The class as a class had ceased to exist.

So the world changed and the forms of struggle and organisation that had helped the working class get good deals ceased to work and there was no reflection or critical thinking about this. And given that a feature of this period was the wholesale destruction of British manufacturing and transference of capital overseas there was no internationalism – that again was left for the fringes to toddle of to Cuba and make glowing reports of how wonderful everything there was.

If anything the very ‘success’ of the trade union push and shove to get a better deal in the post war period led not to a strengthening of the working class – as a class fighting for the class as a whole – but to its fragmentation and degeneration. Could the miners and printers have ‘won’ – yes they could but this would have required the class to begin to act as a class. For me at the time this was prevented by the rotten leaders but if this was the only problem then why was there no signs anywhere of people pushing back against these rotten leaders? Where did workers disregard their union bosses and take solidarity action? Nowhere. In my factory we only won 25% of votes for strike in support of the miners and ever day down the line that percentage would have been less and less. Every defeat, and there were many, convinced people that a fight against the bosses was pointless and of course, in a sense, they were right. If production can be moved to China whats the point of going on strike in the old way to defend your jobs.

Its instructive that the only serious defeat inflicted on Thatcher came when the working class took to the streets not organised by the unions or the labour party but in the poll tax riot. And in some ways that defeat was the beginning of the end of Thatcher but not Thatcherism which was continued by Tony Blair and the Labour Party who rode in to fill the void when the Tory party began to implode at that point.

Now its 20 years or more since all of these events and yet when we discussed the Tower Hamlets strike someone said ‘what can you do if the workers are not really up for a fight?’. A Heathrow worker sends the reports of workers fighting each other for jobs. Do those defeats of the 1980’s still carry weight? Haven’t new generations of workers taken the place of the people who suffered those defeats?

What those defeats made possible was the move of industrial capital out of the UK. And they broke a certain continuity of ideas and organisation. For example in my work I would often be training an apprentice. They would start work and complain about having to go to the union meeting. But they had to go or lose their job. Slowly they would get to see the point of us all sticking together and so on. That continuity of class organisation was broken by the destruction of manufacturing. That sense of solidarity has gone. But then it wasn’t really the defeats that ended it, rather it was a form working class activity that itself degraded these ideas, that couldn’t sustain itself when faced with a new form of ruling class attack.

Of course there are many factors behind the present ‘passivity’ but what’s for sure we cannot go back to the old militancy which many old lefts dream of and reminisce about. The whole of the Corbyn ‘dream’ was based on this illusion. The world has changed. And it leaves today’s militants with a great problem. Capital is no longer able or willing, on any sustained, permanent, basis to make concessions as it did. Anything that it has to concede in the face of a fight it will immediately seek to take away again. Its ability to move to any part of the globe undermines any long term fight that is not internationalists in forms of organisation.

So we cannot simply ‘rebuild’ the trade union movement. The workers movement has to rebuild its class consciousness and class consciousness today has to start with a recognition of the world as it is – globalised, destroying the conditions for life and totally incapable of being reformed.