Mutual aid, social reproduction, and crisis in South London

Introduction

We set up Croydon Solidarity Network six months ago. Our aim was to firstly follow a model of workers inquiry with respect to the working class of Croydon, and secondly to experiment with forms of organising within the area. We envisaged this as being rooted in workplace organising, but also extending to other issues affecting the class, from housing, to state violence, to family life. The pandemic has put some of our plans on hold, but in other ways it has accelerated our work. Here we take a first opportunity to look beyond the workplace at the question of social reproduction and the role of ‘Mutual Aid’ groups.

Much has already been written about the groups that popped up across the UK in response to the pandemic and lockdown. As with a lot of leftwing analysis, these articles have often started and ended with a focus on organisational form and the activists involved in the mutual aid groups. We think that we should at least start from the subject of working class social reproduction during the pandemic and look at what kind of organic mutual aid may have existed in working class circles. Only from that basis does it make sense to look at the formal mutual aid groups and what their potentials and limitations have been from a class power perspective. Therefore, for this article we spoke to around two dozen warehouse and retail workers in Croydon, as well as several of the main activists involved in the mutual aid network.

Coronavirus and social reproduction in Croydon

The crisis has hit Croydon hard, even by the UK’s woeful standards. Recent figures from Public Health England put Croydon as the local authority area with the fifth worst death-rate in the entire country, and double the national average. (Two of the authorities with worse death rates are neighbouring Lambeth and Lewisham.) The Labour-run council is on the brink of bankruptcy, with a £62million pound budget deficit. So far, it has responded by announcing 400 job cuts, imposing a recruitment freeze and stopping all ‘non-essential’ spending. Domestic abuse is running high in the borough, with 562 reports in the first six weeks. There is an increase in funeral poverty, due to the sharp rise in deaths and by mid May the number of food banks and soup kitchens in the area had quadrupled. Clearly, there is a lot going down that’s making life hard for working class people in Croydon, as well as the neighbouring areas that we explored for this article.

We wanted to look at some of the experiences of community support and reproduction of people in the area, and their familiarity with the Mutual Aid groups. In carrying out the background research for this, we spoke to just over 20 workers in warehouses and food outlets in the wider Croydon area. The workers were a diverse cross-section in terms of gender, country of origin, race and age. These conversations were not as in-depth as we would have liked, and 20 is not a huge sample size, but this at least gives us some sense of the problems people are dealing with, the reach of Mutual Aid groups amongst the workers we are focusing on, and what kind of essential support workers were aware of or using in their neighbourhoods.

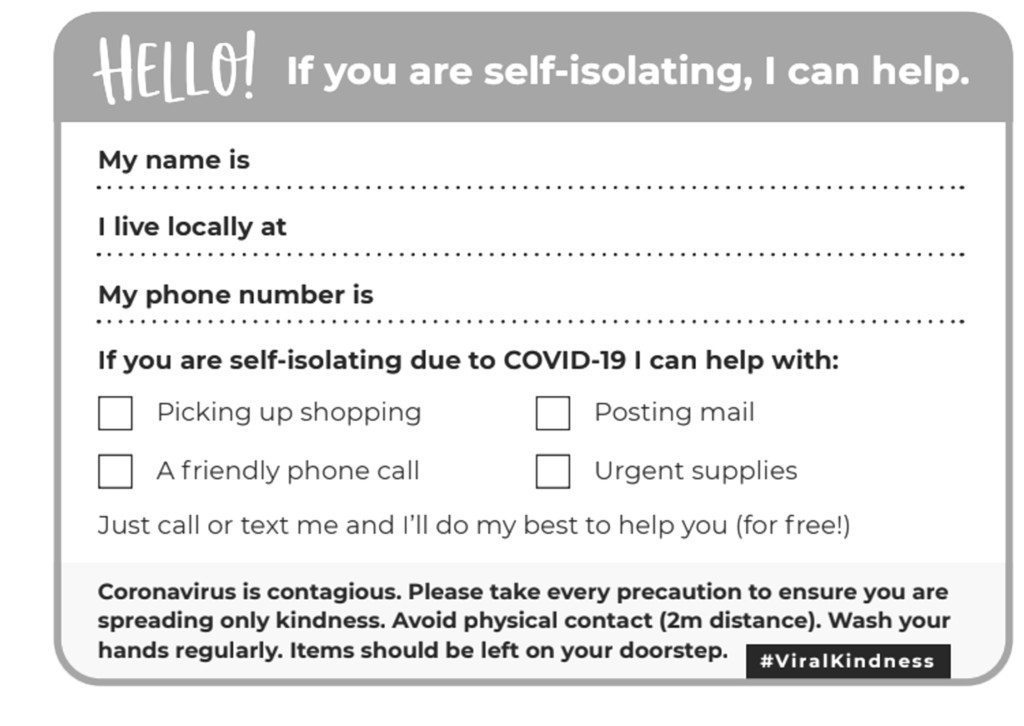

Of the workers we spoke to, around one in four workers had heard in some basic way of the mutual aid groups. Some had received a flyer through their door, while others had seen or heard something on social media. Of those who had heard of the groups, none of them could tell us in any detail what they did. One person was worried that they were a scam because his 80 year-old father had received scam calls during the lockdown.

Workers brought up various problems that they had been dealing with during the pandemic and lockdown. Inability to pay rent was very common, as was difficulties with paying bills and for food. Hunger came up too. There were also issues around family breakdown, and people having to move out of the city. And the backdrop to this is often job losses, unemployment or the threat of unemployment.

When asked about what forms of neighbourhood/community support workers either used or were aware of, people mainly listed local soup kitchens and food banks as the main sources of support. Others listed churches and mosques as offering support and food deliveries. One person’s sports club raised money for affected members. Another person associated community help with the council.

On a more positive note, one person spoke of a pre-existing whatsapp group for her area that was used to pool collective resources and information and to coordinate support. Meanwhile at one warehouse, a group of Polish workers used a whatsapp group to collectivise online shopping and coordinate other support. But the most common thing people mentioned was simply family. There seemed to be a major barrier between people being ready to ask or give help beyond their close family circles.

Again, these explorations aren’t as deep as we would have liked them to be. It’s hard to build trust with people to go beyond basic or even light-hearted conversations about the lockdown and surviving the pandemic. But what’s clear is that trust and organic connections are the common threads in the types of support that workers brought up. It’s the soup kitchens that have been in the area for years, the church groups with a regular and fairly deep basis, and the family ties that somehow provide the most basic level of trust and security in an otherwise divided class landscape. These are the characteristics that need to be replicated by any serious neighbourhood organising effort. And as discussed above, the issues currently facing the class are vast and severe – domestic abuse, hunger, homelessness, unemployment. This is the highly challenging but realistic departure point from which we need to look at any large organising efforts like the mutual aid groups.

Background to the mutual aid groups

The first mutual aid group was set up in Lewisham as a Facebook page, by a few individuals with links to leftist/autonomist organising across south London and beyond over the past decade. One of those individuals went on to set up the mutual aid UK umbrella group, encouraging the establishment of groups across the UK, sharing resources including leaflet templates. On the website, Covid-19 Mutual Aid UK states:

“Mutual aid isn’t about “saving” anyone; it’s about people coming together, in a spirit of solidarity, to support and look out for one another.”

It’s difficult to estimate how many groups have formed, or how many people have become involved but it’s certainly in the thousands. The Croydon Mutual Aid Facebook group has nearly 4000 members, whilst Lewisham has over 6000. However, it’s in the street or ward level groups that people are organising themselves. At the height of the lockdown, most wards in Lewisham had their own group, with less coverage in Croydon but still a substantial part of the borough covered.

Unlike Lewisham’s ‘political origins’, Croydon was set up by a healthcare worker who saw the forthcoming need for community support, mainly around the delivery of food and prescriptions, specifically for people who may feel unable to leave the house due to age and/or underlying health conditions. That healthcare worker quickly stepped back, and a group of admins/coordinators emerged who were loosely linked to one another via Labour Party membership and organising. The involvement of Labour Party activists is, perhaps unsurprisingly, a common theme across Lewisham, Sydenham and Croydon, but differs from other areas where the local Labour Party structures actively set up or took over mutual aid groups, for example in Wandsworth.

Mutual aid activists report that it quickly became clear that borough-wide mutual aid was not going to be effective, and what was needed was a more local response. In Croydon there was an emphasis on establishing street level groups and then using the central group to point people in the right direction as and when they got in touch. In Sydenham, 400 people joined in the first fortnight, which was difficult to manage at ward level. Initially, Sydenham attempted to do this themselves, with around 20 admins emerging and beginning to put things in place. However, the contact we spoke to in Sydenham said that in hindsight this may have been the wrong approach. A dynamic that set in, was people waiting to be given something to do and deferring to a leadership that did not exist. Neighbouring Forest Hill had instead pushed everything towards street level, which seemed to improve participation.

From our personal experience, and backed up from the interviews with the admins/coordinators, the focus has mostly been on food distribution and collecting prescriptions. Groups leafleted houses in their street or ward providing contact details to either get in touch to help, or to let the group know if support was needed. Other activities included dog walking and posting items. In short, tasks that people who were shielding did not feel able to do.

Class composition: who uses and who provides ‘mutual aid’?

It is difficult to generalise, but in Sydenham there seems to be a propensity of white-collar professionals being the most active. This includes people from caring professions (social care, therapeutic backgrounds) and lawyers. In Croydon, it depends from ward to ward, but certainly many have similar professions to that of Sydenham, mixed with other wards where pre-existing housing associations have taken on the role of mutual aid groups. In the neighbouring street level group to where some of us live in Lewisham, there are mid-level managers from the private sector and a classical music composer. In fact, this street level group has seemed to become dominated by discussions around how to collectively buy organic food produce and organise socially distanced cocktail parties. In short, there is a distinctly middle class feel to some of these groups and this is reflected in their activities and attitudes.

However, it’s not a uniform picture. For example, in Bellingham. Most of those going out to get food or perform tasks are middle aged working class women who have lived in the area for their whole lives. Bellingham, unlike Sydenham, has not seen gentrification occur on a large scale. Home to what was, until recently, the largest housing estate in Europe, Bellingham is dominated by high rises, small shops and the busy road that takes traffic out of Lewisham towards Bromley and beyond.

In terms of who then looks to access support, the activist that was spoken to in Sydenham said that they had limited contact from the residents of local estates despite extensive leafleting, and his hunch was that either those people were going through the local food banks, or were mistrustful of the mutual aid group. The likely result is that those in Sydenham who were looking for support from the group, were probably mostly within the (lower) middle class bracket, whilst working class people either continued to go out regardless of whether they felt it was safe to do so, or had to look to the local council for food package deliveries via the food bank. Interestingly, this division came to the fore within the Croydon mutual aid coordination group, where one individual questioned whether mutual aid should get involved where people were facing an issue that preceded covid. The individual cited those accessing universal credit and the unemployed as those who should be left to follow the same avenues of support they had accessed prior to the pandemic. This point was apparently shut down and did not go on to reflect how Croydon continued to practice, but the fact it came up perhaps shows an attitude that some may hold. It raises questions about distinctions of the deserving versus underserving poor.

Mutual Aid, solidarity or charity

In theory, mutual aid groups offer a radical alternative, to how communities are organised but the fact this occurs within the broader structures of the state and capitalism produces shortcomings. A consistent theme from the interviews seemed to be people deferring to those structures. Whether it is becoming bogged down in discussions on GDPR, or volunteers waiting to be told what to do by some kind of authority. A trend also seemed to appear in which there were distinctions between volunteers and ‘service users’. The mutual aid whats app groups often do not include those who are requiring support, and instead the groups form a place in which requests are brought and then allocated. We would see a pure form of mutual aid as not differentiating in this way. It seems that mutual aid groups come to mirror a model closer to charities rather than something more radical. In fact, some mutual aid groups outside of London have had discussions about how to formalise themselves as charities and apply for charitable status.

There have been debates within various mutual aid groups as to whether it’s acceptable to buy alcohol and tobacco products for those shielding. Largely it seems that groups have accepted that this is fine, but the discussion has become more complicated in cases where groups have managed to source money to provide a ‘emergency fund’ of sorts. In Croydon, some money was accessed from the local council (this actually is contrary to the advice given by the UK mutual aid coordination group) and local charities. The result is that quite quickly, the volunteers became involved in gate keeping, i.e. decisions on what people should or shouldn’t be allowed to get. Speaking to the contact in Bellingham, over time they had regulars, usually elderly or with pre-existing health conditions. In Sydenham, the group became aware that a local care home was struggling to get together enough food to feed the residents. A discussion was had within the group about whether they should intervene and attempt to get together food for the home. There was some discomfort about this, as the home was ultimately owned by a private company, but then on the other hand the residents were in need of food.

An ongoing discussion within the Solidarity Network is how to avoid becoming seen as a ‘service’. Organising with the Pizza Hut workers, there were occasions where it was felt that we were being deferred to as experts in some way, who could solve the issues for the workers. We had to try and push back against this and attempt to move it into a practice of solidarity. This is perhaps what piqued our interest in the mutual aid groups and how they navigated this issue. An issue often faced early on in working class struggles is that people look to defer to agencies or organisations. Part of being disempowered is that there is an assumption that solutions cannot be found within the community or amongst their fellow workers. We find this in the trade union movement too. When leafleting at a Royal Mail depot in June, numerous workers would shrug and say, ‘I leave that to the union’.

Purpose and future

Beyond the provision of food, there has been some push within groups for other responses to need in the face of covid. For example, organising against landlords trying to pursue evictions and supporting workers whose bosses were using the pandemic to further attack conditions. These efforts to widen the action of the groups were met with unease by some of the participants. Comments were made about not politicising the group or prioritising an adherence to the mantra of ‘stay at home’ rather than going out to the street. At least in this corner of south London, this kind of mutual aid didn’t take off or become part of the fabric of what groups were doing. The Solidarity Network’s most significant direct contact with mutual aid groups came about during the Pizza Hut campaign. The actions that were organised, were posted on the Lewisham and Croydon mutual aid Facebook pages, and also in a few of the whats app groups. Initially posts were deleted by admins, and we had to get in touch directly with more sympathetic administrators to ask them to get that decision reversed. Once the posts were up, they did generate positive comments and engagement, but there were also several comments criticising the action. Again, the stay at home mantra ruled for these individuals. Sydenham made a decision as a group not to officially endorse the first formal action that took place in the neighbouring area, Penge. In the end, there were a few people who came to the action who had seen it via the mutual aid groups. However, a week later, we became aware that one of the Pizza Hut workers was struggling to feed himself and pay his bills. We got in touch with the local group, and within an hour they had organised a food packaged to be delivered to him. The response was proactive and very welcome given the circumstances.

This raises an interesting point though. It would seem that mutual aid groups have become centred on support with food and other matters related to sustenance. The loss of jobs, pay or even a home, less so. Food has become a safe place for mutual aid groups to operate within, it is not seen as contentious and the vast majority of the membership of the groups is ready to act when there is a perceived need. The reasons why this is seen as ‘safe’ are perhaps numerous. One may be the growth and acceptance of food banks since the financial crash. Another may be a more historical association with charity and Christianity, giving to the poor whilst failing to challenge the conditions that have created the situation in the first place. Unfortunately, the possibility that the groups can fall into a service user model, whilst not challenging the conditions, could be seen as reproducing the deficiencies, or even violence, of the state. Charities can often be found in places where people are in need and have little to no hope of the state intervening, but by becoming involved in those areas they to an extent paper over the cracks. This is done instead of, or in conflict with, that need being met with working class solidarity and empowerment.

All the admins that were spoken to as part of the research for this article, had ideas for what could become of mutual aid. This included a food cooperative model (see Cooperation Town) and linking up with the London Renter’s Union. However, those spoken to also acknowledged that moving to these kind of practices will require an ongoing process of education amongst other active members within the groups.

Conclusion – how does the working class reproduce itself in times of crisis

At the time of writing, the lockdown has been significantly eased by the government, and the public seem a few steps ahead. Packed beaches in Bournemouth, Liverpool fans congregating to celebrate their first league title in 29 years, and a rave in Croydon slowly coming to an end at 6am. Mutual aid groups appear less active, with less and less people shielding and an element of normality returning. It may be that the moment is about to pass, and this begs the question are mutual aid groups rooted? Will their structures exist in a post-covid world? Undoubtedly the struggles that some people face in feeding themselves day to day will remain, perhaps in even greater numbers than before the pandemic. But the capacity of food banks has expanded over the course of the crisis, and as previously stated, those accessing such sources of support didn’t seem to see mutual aid as an alternative. Relationships have been built though, amongst neighbours and within communities, and these could be fostered further and used to do something new and exciting.