We reproduce this informative and accessible article from a comrade currently living in China, a tech worker, who is trying to get to grips with the US-China trade war. China’s economy has come under the spotlight again during the Corona epidemic. Conspiracy theorists think China released the virus into the world in order to accrue economic advantages – although we’re not sure what figures they are basing that on! Some commentators have implied that China’s authoritarianism in response to the outbreak was exemplary, thus sidestepping the thorny issue of being a police state! China caring more about ‘people over profit?’ – that’s a new one! While Corona wreaks havoc on economies around the world, there is understandable fear and uncertainty about how the crisis will play out. To gain a fairer assessment of the state of capital, we only need look at the preceding trade war between the global super-power and its upstart challenger to see that things were already coming to a head. Taking a closer look at the US-China trade war gives us an insight into capital’s unsolvable contradictions and helps break down the myth that capital is in a strong position. It has never been weaker. The question then remains: will the global working class struggles, in particular in China and the US, find a way out of the mess?

The original appeared in the German magazine, Wildcat, in Winter 19/20 and a subsequent English translation followed on the Chuang blog. [1] This version is slightly different again, combining an original translation with some additional comments from the author’s Chuang text. We printed another great article from this comrade a few weeks ago about China’s response to Corona, which can be accessed here:

https://angryworkersworld.wordpress.com/2020/03/25/the-corona-crisis-a-letter-from-a-comrade-in-china-did-china-buy-time-for-the-west/

[1] http://chuangcn.org/2019/12/trade-war-or-redistribution/#sdfootnote14sym

Redistribution or trade war?

In January 2018, the US government imposed the first import duties on a number of Chinese goods, including washing machines and solar panels. This evolved into a tit-for-tat escalation of tariffs applied by Washington and Beijing, punctuated by transient ‘truces’ for negotiations. The tariff war has involved into escalating conflicts over technology, investigations of US-based Chinese researchers, intensified scrutiny of overseas Chinese living in the US, and even the realms of culture and sports. Now, there is also a budding currency war (in which the ECB is also playing a major role, with negative interest rates pushing down the euro). The depreciation of the Yuan by 10 percent since the outbreak of the trade war is: an attack on Chinese workers’ real wages; a direct transfer of income from Chinese consumers to the export industry where consumers experience declining purchasing power; and exporting businesses increase sales of their goods through cheaper prices.

In the global crisis 2008/9, “Chimerica” or the symbiotic relationship between China and the US ended: China had sold manufacturing goods to the US and hoarded US dollars which were invested in US government bonds. This supported low interest rates and a real estate boom and enabled US consumers to buy even more Chinese goods. After the crisis, Obama promoted containment through free trade agreements like the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with Europe, and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) around the Pacific rim, both excluding China. After both trade deals failed, Trump is now focusing on a confrontational approach to China, and is resorting to bilateral negotiations, rather than large, multilateral trade deals, as well as tariffs to put pressure on China (and to some extent on Europe). Confronting China, and slapping tariffs on foreign goods, also helps convince his electorate in US rustbelt communities and rural agricultural regions that he would win better conditions for them.

But the goals of US-China policies haven’t fundamentally changed under Trump, likewise the military strategy for the Pacific has essentially stayed the same. Whether this is intended to produce a decoupling from China and a thwarting of this rival nation’s economic development, or whether it is about greater profit-sharing in this development, depends on the course of the conflict. At any rate, the strategy to ignore the WTO and rely on its own weight as a sales market in bilateral negotiations, is not new. Already before Trump – between 2000 and 2006 – the number of bilateral trade agreements quadrupled. Trump’s protectionism is supposed to be a means of enforcing improved market access to China for foreign companies and free trade in the global economy, but the end result may be continued protectionism and declining world trade.

With the introduction of tariffs and restrictions against Chinese companies (like the ban on communications giant Huawei), the USA is acting like the aggressor. Up until last year, the Chinese government had always been willing to compromise, give in or hold out and make promises. The central question that will guide me through this article is: why haven’t they avoided the escalation this time round? And why are they choosing this course of action at this point in time?

In order to understand this change in strategy, we must firstly see how wages (and wage increases) were financed up to now. After all, economic and trade policy are fundamentally determined by this dynamic.

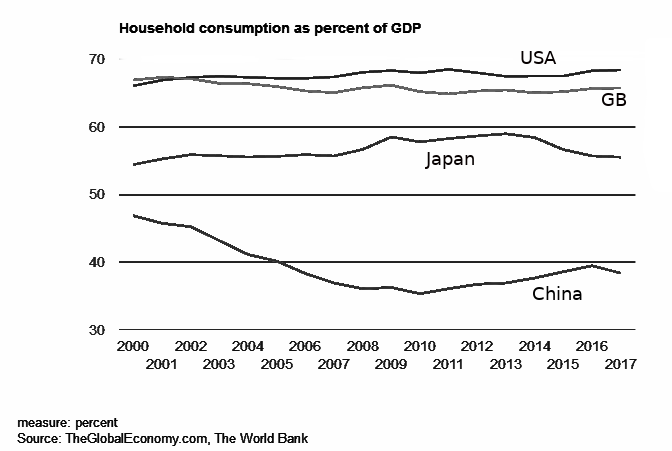

The Chinese Model: Investing not spending

China’s growth model has been based on high investment rates since the end of the Mao era. With the reform and ‘opening up’ of the economy (officially announced by Deng Xiaoping in December 1978), investment as a share of GDP has grown dramatically. And with China’s entry into the WTO and rapidly increasing exports (surpluses), by 2008 it has risen to almost 45%. At the same time, the share of private consumption as a proportion of GDP fell. (GDP is calculated as the sum of private and state consumption, investment and export surpluses.) If export surpluses and high levels of investment occur simultaneously, the share of consumption must be extraordinarily low, and this is indeed the case in China. Until the end of the 1980s, the share of private consumption was just over 50%. But in the 1990s it dropped below that. From 2000 onwards it fell especially quickly and reached 34% after the onset of the financial crisis in 2010. Such a low share of consumption is regarded by many analysts as historically unique.

The following graph shows that the share of private consumption in Japan, Britain and the USA has stayed roughly the same over the last 20 years. India’s private consumption moved between 57 and 60% of GDP; in China it was already much lower than these economies in 2000 – and has fallen even further since then. (How people in Japan, the USA and UK maintains its level of consumption/standard of living despite falling real wages is another question: taking on more jobs, debt…)

The high level of investment, especially state investment, was thus financed by the fact that wages constituted a very low share of total economic output. During the export boom and growing export surpluses, the Chinese central bank bought up the dollars earned by domestic exporters with Yuan. This rapidly growing money supply financed increasing levels of investment. Normally a rapidly growing money supply leads to a devaluation of a country’s currency. But thanks to the high export surplus, the central bank had room to manoeuvre and, conversely, had to weaken the appreciation of the Yuan by rapidly increasing the money supply. So printing money had two advantages: it financed the boom in investment and it helped exports because of the lower value of the Yuan. This was, of course, paid for by Chinese workers, whose share of the growing wealth shrank steadily, while individual income and private consumption have risen in absolute figures since the 1980s. So factory wages for migrant workers rose by around 5% every year between 2000 and 2009 – while nominal GDP rose by almost 19%, so almost four times as fast.

The state set the framework for this gigantic redistribution (from bottom to top) primarily through three measures: downward pressure on wages, compulsory savings at low interest rates, and subsidies.

* Redundancies in state-owned enterprises meant social benefits were lost, the social wage decreased, and pension and health care costs were passed onto the workers. Wages in the industrial centres were kept low by absorbing surplus labor from the countryside, which stemmed from the baby boom years of the Mao era, also known as the ‘demographic dividend.’ Migrant workers’ reproduction costs fell due to the Hukou system (a household registration system), which excludes rural residents from social benefits like healthcare, education or housing rights in the urban centres where they live and work. Even today, about 50 million workers’ children do not grow up where their parents’ are working, but on their grandparents’ (cheaper) land. In addition, independent trade unions and other organisations remain prohibited, as they have done since the 1950s.

* Also, even during the boom years with the growth rate in double digits, (savings) interest rates were significantly lower than the growth and profit rates. Small investors, and in particular wage earners who have to put money aside for if they get sick, buy a home, educate their children and make provisions for old age (private savings rate in China is 30%; in Germany it’s 10%), have lost considerable sums of money to borrowers, i.e. companies and the state.

* The provision of relatively cheap land and even lower levels of compensation for former peasant farmers represents another important form of subsidy for companies who buy up cheap land for development. And finally, allowing environmental destruction and the pollution of proletarian living space is also a form of state subsidy to businesses.

2008 crisis

The growth model came to its first deep crisis with the crash in exports, as that investment could no longer be financed through export surpluses. The American half of Chimerica was closer to the heart of the crisis. At first it looked as though China still had the greatest room for manoeuvre in this situation: As early as 2009, massive debt-financed infrastructure programmes were launched, which together accounted for almost a third of GDP – historically one of the largest crisis rescue programmes ever, without which the global economy would not have come out of the hole so quickly. As a result, between 2009-14 the share of investment as a share of GDP once again shot up to 48%. During this time, three times as much concrete was used inside China within three years as in the USA in the whole of the 20th century!

The low point of private consumption (as a percentage of GDP) in 2010 coincided with a massive strike wave (starting at the Honda transmission plant in Guangdong), which followed two years of wage stagnation. Strikes, increasing demand for workers in the booming construction industry, and higher minimum wages led to private consumption as a share of GDP between 2015 to 2015/6 to rise to 39%. The wage gains of migrant workers since 2010 were also reflected in the ratio of wage to GDP growth, and between 2011 and 2014 they were above nominal GDP growth. Between 2011 and 2014, wages grew at 9.5% per year above the nominal GDP growth of 8.2%. For the longer period between 2005-16 the picture is as follows: GDP grew almost fivefold; factory wages almost tripled to $3.60; GDP grew annually by 15.5% and wages by 10.4%.

At the beginning, growing profits as well as (slower increasing) wage levels were both financed by the export surplus. Since the 2008/9 crisis this was kept going through increasing levels of debt, with total debt rising from 2007 to 2014 from 158 to 282% of GDP. Meaning that for every percentage point of growth, debt rose by more than 2 percentage points. But it was precisely during this phase that workers were able to fight for wage increases above GDP growth levels. Therefore, debt-financed growth couldn’t be continued. In Guangdong, for example, after the 2010 strike wave, some experimentation with company unions, company elections and wage negotiations were allowed to take place. But that only lasted a couple of years. Since the 2015 stock market crisis, the government has been mixing strategies – between reducing debt levels, encouraging some debt-driven economic development, combined with repression. It is taking an increasingly heavy-handed approach against labour NGOs, and the demands for wage increases, or the payment of wage arrears.

2015 stock market crisis

From 2013, in order to raise additional funds to sustain investment driven economic development, the financial sector was liberalised. As a result, there was a brief equity boom with price gains of over 100%. This imploded in the summer of 2015, causing, amongst other things, capital flight. Foreign exchange reserves melted by around 900 billion dollars. At this point, since 2016, the Chinese government ended their efforts to internationalise the Yuan and they tightened up their capital controls again.

The 2015 stock market crisis marked a dramatic turning point, as the relative growth of consumption and wages was curtailed – since then no-one can realistically talk about a strategy of increasing internal demand! Despite government propaganda to the contrary, no actual re-balancing towards the domestic consumer market has happened since then. The anti-corruption campaign launched under Xi has forced the party bigwigs to be more cautious in their business dealings, and growth in government investment has declined. The government is trying to sell the slowing investments as deleveraging (debt relief); but in reality, debt as a ratio to GDP continues to grow, just more slowly.

Moreover, “private household” debt is accelerating. Between 2015 and 2017 it has risen from 39 to 49% of GDP and reached 55% in the summer of 2019. This seems low in comparison to the USA where private debt is 76% of GDP. If, however, private debt is compared to average disposable income, a more relevant comparison than with GDP, we see that private households currently have a debt level of around 126% of their income (for the USA this ratio is 98%).

Since autumn 2018, the government has reacted to the slowdown of economic growth again with an expansion of infrastructural investment and increased new borrowing. Total debt stands at between 300 and 315% of GDP, depending on the calculation, and the Bank of International Settlements expects an increase of seven to eight percentage points in 2019.

And although the number of (mainly private) company insolvencies is increasing, most loans are always rolled over when they’re due. All of this is happening against the backdrop of a shaky banking system. In the course of the restructuring of bad loans, interesting details have been made public: Chinese banks, for example, sold off more bad loans in 2018 alone than they had listed in their books! Probably nobody knows exactly how many bad loans are still hidden in the banks’ books.

The situation today

The statistics about China’s economic development need to be taken with a pinch of salt. Nevertheless, they clearly show that the absolute and especially the relative share of consumption in China is still very low and has been stagnating for years – despite all the propaganda of strengthening the domestic market.

* The share of consumption is stagnating at 39%, which is about 29 percentage points lower than the USA (68% according to the Federal Reserve in St. Louis). In absolute terms, private consumption at the end of 2018 was 19,853 yuan (or about $2,971) compared to per capita GDP of 64,644 yuan (9,675 dollars). By comparison, at the end of 2018 the USA had a GDP of around $57,170 dollars per capita and private consumption of $42,415 per capita (i.e. a share of 74%, the deviation from the above percentage figure is due to different methods of calculation). So while China’s GDP per capita has reached about 17% of the US level, private consumption per capita is only 7%. Germany is also financing its export surpluses through a relatively low share of private consumption of GDP, which fell from 58 to 52% between 2007 and 2018.

After having slightly decreased after the crisis, inequality in China has increased again in recent years. In 2018 the Gini Coefficient reached 0.5, on a par with Brazil and Columbia. Rising inequality again puts pressure on consumption (as a share of GDP) because the rich buy designer handbags and expensive watches, but consume significantly less as a percentage of their income.

* Foreign direct investment in China fell in relation to GDP by over 3% between 1999 and 2012. Today it stands at around 1.5% of GDP. It doesn’t play the same role as ten years ago.

Exports have also lost considerable importance. Before the global crisis they peaked at 31% of GDP. Since then this share has been falling, and since 2014 exports have hardly risen at all, even in absolute terms. Their share of GDP stood at 19% at the end of 2017. Imports as a share of GDP show a similar trend but is characterised by stronger ups and downs as a result of growth slumps in 2015/2016 and 2019; its share of GDP was 18% in 2017.This means that imports and exports in relation to GDP in China are roughly on a par with India’s exports of 19% and imports of 22%. Germany’s extreme export-orientated economy accounts for 47 and 40% of GDP respectively, France for 31 and 32%, and the USA for 12 and 15%. China’s foreign trade surplus fell to 0.4 percent of GDP in 2018 and is estimated to turn negative in the coming years.

* State infrastructure programmes are becoming increasingly inefficient. Just to name one example amongst many: the utilisation rate of China’s metro system (passenger per kilometre) is only two thirds the international average. Since the subways in the major cities are very busy or overcrowded – half an hour of queuing during rush hour is not uncommon – this means that many newly built subway lines in other cities are grossly under-utilised. This is not due to the lack of people, but because subway construction is oriented towards investor interests and land development plans.

* Investment is very unevenly distributed across the regions. While for some time many economically backward provinces were able to catch up with higher growth, over the past few years they can at best just about keep up with the coastal provinces. They cannot hope to speed up and bridge the gap. In the future, they will probably fall further behind the major industrial centres and become even more dependent. US tariffs have made it even less attractive to relocate production facilities from the more expensive coastal areas to the interior of the country.

The governments of many poor provinces are heavily indebted compared to the national average of 60% of provincial GDP: Qin- hai (80%), Gansu (85%), Yunnan (115%), Guizhou (170%). Last year, plans for the development of three big regions were publicised: the region around Shanghai, the Greater Bay Area with Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Guangzhou and Macau, as well as the region around Beijing and Tianjin. Immediately, house prices in these regions shot up. This continues the redistribution of wealth in favour of property owners in the metropolitan areas. Migrant workers don’t often go back to their villages, rather to developing cities near their former villages. Everyday consumer goods are only slightly cheaper there than in the bigger cities, but the wages are lower and the schools are worse. With falling investment in infrastructure projects, jobs are becoming more difficult to find.

996

Authoritarian management styles are not getting better either. At the beginning of 2019, an online discussion sprang up about the 996 work system that is widespread amongst Chinese tech companies. ‘996’ stands for: from 9am-9pm, 6 days a week. It’s not only in factories that overtime is widespread – it’s the same in offices. The 996 system was developed in software companies around 2014, when the demand for programmers exceeded the supply and companies were ready to pay higher wages for longer working hours and to offer good chances for career progression. With the sharp withdrawal of venture capital in 2018, many software companies began to sack employees. The overtime stayed, but wages no longer rose so much and opportunities for advancement dwindled. This may well have contributed to the fact that the middle class suddenly became angry about wages and working conditions. Despite the online discussion having so many lively and numerous voices, nothing practical came out of it. Among the most well-known companies operating the 996 system or defending it in the public debate are Huawei and Alibaba. It is significant that the same tech bosses who want to protect their future profits with self-driving cars and computer chips, like Jack Ma, former boss of Alibaba, are the most vehement defenders of unpaid overtime and the 6 day working week.

‘996’ shows how Chinese bosses intend to apply the same management system used in Chinese factories to software production. While wages in tech are higher, and they rely on cheap incentives like free pizza while workers stay in the office until 9.30pm, the aim is the same: the extraction of absolute surplus value through the hiring a young workforce and the maximal expansion of the working day. Given the fact that hours worked are already high, it will be difficult to compensate for rising wages through intensification of work. The management in companies like these is authoritarian or, in the best case scenario, paternalistic; decisions are made at the top, whoever is below follows them, and is considered inexperienced and unimportant. So programmers, like workers in general, often change jobs, to improve their pay little by little. The redundancies in the industry are now making this strategy more difficult. You don’t have to believe in the illusion of horizontal hierarchies to see the inefficiency of such management in software manufacturing. In programming, where the training period and the share of internal project communications are relatively high, you won’t get far if people are constantly coming and going and only managers are talking in work meetings, even though they are not involved themselves in working on the actual code. This is a common problem in the software industry in other countries, too, as new, so called agile management forms were introduce to engage programmers in the whole development process. Even though buzzwords like “agile” are common in the IT industry in China, as the 996 debate shows, these are often only fashionable names for unchanged authoritarian management. Overtime usually results from poor project management, but when those who work the longer hours are given no choice but to sacrifice their free time and are discouraged from giving feedback, little will improve. At present, the costs arising from such inefficient work organisation can still be offset by venture capital, the large Chinese market and low wages in other sectors. The 996 debate thus shows how little bosses in China are willing to move away from authoritarian labour relations, even as new industries emerge.

From labour surplus to labour shortages

The number of (internal) migrants hasn’t increased much in recent years, at around 280 million people. Their average age has risen from 34 to 40 years old; over 50s now make up almost a quarter. With older people, you have more experience in dealing with fraudulent bosses. In terms of wages and their increases, there are clear differences between industry and logistics on the one hand (which rose by 6.8% to around 4345 yuan in 2018) and services and the hotel and restaurant industry on the other, (which rose by 4.3% to just over 3000 yuan in 2018). Since 2018, the average wage for white collar and higher skilled workers has grown by around 7%.

Fewer and fewer young people are willing to work in the factories, which is reflected in the higher wage increases in industry compared to the service sector. Every year, over 8 million university graduates enter the labour market, who have invested a lot of time and hard work into their degrees, which brings with it higher job expectations – like the fact that the wage increases we’ve seen over the last couple of decades will continue. The rapid growth of online commerce and internet services such as food delivery, taxis etc. have provided some extra jobs for a while, with new, venture capital subsidised jobs in the service sector. Now, however, growth rates are collapsing here too.

Workforce numbers are now shrinking and this will only accelerate in the next few years. Between 1978 and 2010 the so-called working age population (15-64) grew by around 80%, or annually by 1.8% – from 580 million to 1 billion. Since then, it has stagnated and since 2015 has shrunk slightly. This rate of shrinking is gradually accelerating. Between 2015 and 2040 the working aged population will have declined by around 100 million to 880 million and will then fall annually by 1% a year. The decrease is particularly marked for the younger age groups: 15 to 29-year-olds will decrease by 75 million or almost a quarter, 30 to 49-year-olds by 100 million, also a quarter. It is estimated that by 2040, half of all Chinese people will be over 47 years of age and 22% will be 65 or over, which is comparable to Germany today. Official pension age stands at 55 for women and 60 for men. The government haven’t yet dared to raise it. Birth rates are low despite heavy social pressure on young couples to have children. The most important reasons are expensive housing costs, expensive education costs, job insecurity and discrimination of women at work. Even if birth rates rise sharply, this still won’t alleviate the decline in the labour force by 2040. Bringing foreign workers into the country isn’t possible on this scale and would pose completely new challenges to the political order.

Population policies, most significantly the one child policy, have led the Chinese extended family, nucleus of social care and control, first to its historical peak, and now to its decline. The increase in life expectancy and the high birth rates during the Mao period have led to an enormous increase in the number of living relatives and marriage had become the inevitable norm; around the year 2000, over 96% of the population had been married at least once in their lives. That, and the wealth gains of the boom years, has allowed Confucian traditions and family values to flourish over the last 10 years. People in their 50ties, 60ties and 70ties have on average larger networks of living relatives than a 50 years ago. And the wealthy also often celebrate these networks through opulent weddings, funerals etc. But this is a specific and limited historical phenomenon. Because of the surplus of men and in view of the declining divorce rate, a quarter of all men are expected to still be single at 40 in 2030. The positions of power in society and patriarchal families are still predominantly held by men from generations with many children and living relatives. But they are getting old, and with them the extended family will gradually disappear and inevitably die off. In 20 or 30 years, the networks of living relatives will be significantly smaller due to the low birth rates and fewer siblings in each generation and this will likely bring changes for a society which put so much emphasis on family relations.

The old power base vs. emerging tendencies towards market liberalisation

The reform of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) has been stagnating for years. On average, profits from SOEs have risen, but their profitability differs a lot. Some are more concerned with social stabilisation and job maintenance (in sectors such as steel, construction, transport, etc.), while others are very profitable and form state monopolies in the oil, raw materials, banking, tobacco and telephone network sectors. The state-owned automobile sector is also very profitable (although there is no technical monopoly here and there are a considerable number of joint ventures with foreign firms). In total the SOEs only contribute a little to job growth, although they make up 40% of GDP and make up about two thirds of the turnover of (stock market) listed companies. So, SOEs dominate through size and turnover, not through number and least of all through jobs.

The Chinese stock market is essentially a market of SOEs. Its further liberalisation would require the reform of corporate management, especially of state-owned companies, as investors want to be able to influence corporate decisions. So far, this power has been in the hands of the Chinese Communist Party, their interventions having increased even more in recent years. In addition to the influence exerted through legal means, public decrees and via state industries, private (Chinese or foreign) companies also now have to set up corporate Party committees, which increasingly interfere in company decisions. The establishment of company trade unions in foreign companies has recently been expanded too, albeit from orders from above. My department have also had a union committee for a few months now, the chairman is the head of the department. We get cinema vouchers or other cheap presents and the union committee now organises the annual works outing. Otherwise, it only exists on paper.

The financial industry appears to be more open for foreign investment and their desire for reform. Several foreign financial institutions are now allowed to acquire a majority stake in their joint ventures. The liberalisation amongst joint venture companies in other sectors, like the auto industry, shouldn’t be overlooked either. One part of the ruling class wants further integration into the capitalist system rather than a confrontation with the USA. Government-related and former government members utter covert criticism of the political course, seen as as a reversal of Deng Xiaoping’s reforms.

Have the dice been cast?

While the past is gloomy, the outlook is even gloomier. Who will pay for the gigantic mountain of debt accrued over the last ten years? And how should future wage increases be financed? The biggest dangers are a collapse of the massively overvalued housing prices and an increase in unemployment. For years, expectations have been raised that China will almost automatically have caught up and outperformed the USA by 2030. This depends on the rate of growth staying 4 percentage points above that of the USA. While this might be possible this year (in 2019), it can only be achieved by rapidly growing overall debt, so it’s questionable whether such a high growth rate can be sustained. To catch up by 2035, China’s growth would need be around three percentage points higher than the USA’s and to catch up by 2040 it needs a 2% higher growth rate. But by then, the effects of the demographic crisis on the economy – which is difficult to estimate – will already be massive. Having a “lost decade”, as in Japan, with very low growth rates, or a visible defeat in the trade war, would not go down well with China’s nationalist expectations. Population decline stands in the way of China’s role as a world hegemon – and will become even worse in times of trade wars. However, there are a few options left for future economic development:

– If the government were serious about increasing domestic consumption, wages would have to increase and wealth would have to be redistributed on a large scale by the state, from corporations and rich “private individuals” to the working class – while at the same time the economy would grow more slowly! But the ruling elite is not willing to accept such a massive loss of their wealth and power.

– Another option would be to the complete opening up of markets for foreign investors, in other words, the ‘shock therapy’ à la Eastern Europe after the fall of the Iron Curtain. A full opening up of markets, including the internet and media market (as apparently demanded by US trade negotiators), poses a big risk for the Communist Party.

– The reformist option would be to move up in the global value chains and open up new foreign markets by means of imperial geographical expansion – and this is where China encounters opposition from the USA.

Policies in the last few years clearly show that the third option of geographical expansion and moving up in the global value chains is being pursued. It is precisely this move that has led to the ‘trade war’ with the USA.

Industrial policies

‘Industrial upgrading’ in China is so far advanced that it is beginning to challenge the economic superiority of the USA. Productivity gains in toy, shoe, railway, construction machinery, automobile, household appliance factories over the last two decades are not as great a challenge for US industry as current industrial policy, which targets AI, semiconductors, biotechnology, 5G network infrastructure, cloud computing, aircraft construction, quantum computing, financial technology and others. Losing the advantage in those sectors would be painful for the USA – particularly in these times of weak global demand.

Industrial development plans over the last 15 years (like ‘Made in China 2025’) focus on the following sectors: machinery for agriculture; shipping and naval industries; electric cars; new generation information and communication technologies; machine tool systems and robotics; electricity; aerospace; new materials; railways; biomedical and medical equipment. The development of new powertrains, and new value chains like those around batteries for electric vehicles, is intended to establish new Chinese car brands. The growing demand for energy is supposed to be met through nuclear power instead of coal. The world’s biggest high-speed train network needs a lot of locomotives, as well as the mechanisation of agriculture tractors etc. China imports over $200 billion worth of semiconductors and computer chips annually, and the growing domestic air traffic needs Boeing and Airbus aircraft. Here, China’s industrial planners see an opportunity to increase their market share through import substitution in order to invest parts of the enormous investments profitably. With the developments in microchip production, AI etc. it will be the national champions of the last decade in particular that will benefit, companies like Huawei, Tencent, Alibaba and Baidu. Chip production is extremely capital intensive and is already suffering from dwindling profits.

The majority of the sponsored key industries are also relevant for the military. High-tech sectors, industrial promotion and the military have joined forced to form a military-industrial complex that is increasingly being promoted with the development of new weapon systems. The expansion of digital surveillance at home benefits the same high-tech sector.

Growing militarisation

Simply to secure China’s demand for raw materials, Chinese state-owned enterprises have invested considerable parts of their export surpluses abroad. In addition, there are numerous other foreign investments (China’s foreign investments of around 1.5 trillion USD are just behind those of Germany or France) as well as government programmes such as the New Silk Road, industrial parks, ports etc. But since 2017, China’s foreign investments have been declining and investments in the New Silk Road are also lower than expected – at only 400 billion USD in the five years between 2014 and 2018 compared to the several trillion USD they were publicising. The future of China’s investment in the New Silk Road depends on its (positive) trade balance.

China is now the main trading partner of 124 countries. This compares to only 85 countries for the USA. Evidently, this brings along with it the possibility for soft power and influence. In global capitalism, worldwide economic activities require either a co-operation with the ‘pax americana’ system including indirect tribute payments, or you have to have your own global military presence. China chooses the latter and is securing its ownership claims in terms of foreign investments and trading goods in an increasingly military fashion. In the South China Sea, artificial militarised islands are being built, weapons systems are being modernised, aircraft carriers, submarines, guided missile destroyers, ballistic missiles, fighter planes and the first overseas military base in Djibouti are increasing the radius of operations beyond the coastal waters. Work is also underway on new weapon systems such as hypersonic missiles, drones and swarm drones, and on weapons to destroy enemy satellites. The military has also visibly gained power in domestic politics. Xi has increased the military budget, organised large military parades and has recently increased punishment of critics of the military.

In diplomacy as well, the CCP has taken a more assertive stand. The clashes over the THAAD missiles in Korea, the three tourists in Sweden, the arrest of the Huawei manager in Canada, the NBA scandal, and the extradition law in Hong Kong show that more offensive diplomatic tones are also being struck. Beijing was able to persuade other countries to end their diplomatic relations with Taiwan. Beijing wants to enforce the principle of “one country, two systems” for Taiwan, despite it having failed in Hong Kong – and despite the vast majority of the population being against it too.

Wage pressure

The Made in China 2025 plan completely neglects the question of how to skill-up and adjust workers’ training in relation to industrial automation. Increased productivity is conceived of solely through investment in constant capital. There have been repeated government attempts to improve productivity and unit costs in existing labour-intensive industries through greater worker involvement and gradual improvements of the work process. But this is more complicated, takes longer, meets resistance, and is apparently too difficult to implement under the given state bureaucracy, it’s decision-making structures and the power of workers, such as relatively easy job-switching.

In the last few years, wage trends have been relatively stable, although much slower that they were before the stock market crash in 2015. It is difficult to say whether this trend will continue in 2019, as there have already been redundancies in a number of sectors. Minimum wage increases in 2019 in all the provinces have been much lower than previous years. Minimum wages continue to fall relative to the average wage. In the Pearl River Delta area they are only 23-27% of the average wage. In addition, the expansion of formal employment contracts is stagnating, not only in construction and blue-collar jobs, but also in a sizeable number of office jobs. Between 2012 and 2016, the total number of formal employment contracts has decreased from 44% to 35%, meaning that employers save money on social security contributions and compensation for things like occupational diseases etc.

We can see a massive fall in the social wage in sectors like education, apprenticeships, health and care work. The city of Shenzhen, for example, which has recently been designated as a future international model metropolis, only offers 47% of its secondary school students a place at a sixth form college (plus 10% at expensive private schools); compared to 67% in Ghuangzhou and 85% in Beijing. There is supposedly not enough land available to build more schools in Shenzhen, meanwhile 23% of offices stand empty, and more offices – amounting to 80% of the total office space – are currently being built. The resulting competitive pressure is causing a boom in private schools and tutoring.

In healthcare, it isn’t the public hospitals that are being improved, but rather investment opportunities for private hospital operators. Private health insurance is also another potential profit-yielding field because of the rapidly ageing Chinese population as well as the fact that many Chinese people have little to no health insurance. 50 million people have their private health insurance from Alibaba; almost none of them had had any kind of health insurance before. It’s not actually official insurance though so it’s totally unregulated.

The ageing population, where the average age is close to 37, which is on a par with the USA, is matched by a completely inadequate pension system. Employer contributions to the state pension were recently reduced from 20% to 16% while the employee’s contribution remained untouched. That is a de facto 4% wage decrease, but one which is not immediately noticeable. After this reduction in employer contributions, pension fund reserves for municipal employees for example, will be used up as early as 2027.

Since 2017, 600 selected state-owned companies are supposed to transfer company shares to the pension insurance companies in order to increase their pensions, But so far, only five companies have followed these government instructions – here you can see how successfully ‘redistribution from above’ is being implemented!

Repression

Along with the suppression of workers’ struggles comes the general repression against feminists, LGBTQ, punk concerts etc. The police, who banned our single mothers’ discussion meeting about the situation, explained to us that this year especially they have to check on young peoples’ activities. Xi’s anti-corruption campaign, the tightening of censorship, and control over the media and universities, are further examples of increasing influence that is neither legally mediated nor transparent or predictable. The introduction of the much discussed social credit system has been announced for 2020, which will mean more surveillance, data collection, blacklists for undesirables, blatant discrimination and all kinds of bureaucracy, and state coffers will fill up with fines. More than 17 million Chinese people are already blacklisted and shut out from buying plane and train tickets.

It’s still unclear who should pay the rewards for good behaviour and how disputes will be decided. This attack on the working class, which is aided by computers, seems like a nightmare. It is questionable whether a second regulatory system alongside that of the law, police and courts will be less corrupt and whether sensitive personal data will not be immediately stolen or manipulated through cyber attacks.

On top of that, there’s the continuing failure of the authorities to guarantee food and drug security or disease control. Despite a series of state measures to keep prices low, pharmaceutical companies have been able to increase many drug prices significantly.

To summarise the policies on minimum wages, repression and privatisation, it looks like the state tries hard to keep real wages low, although average wages are still increasing significantly (at least until 2019).

The worst swine epidemic of all time

The worst effects were seen in the African swine flu, the worst animal disease in recorded history. They’ve supposedly had it under control since August 2018 but it is still spreading today.

Half of all the pigs in the world are bred in China. In 2018, 56 million tonnes of pork were consumed here. Hog stocks fell by 40% because of the disease, which is more than the total consumption of pork in the whole of Europe. In 2019 production fell by an estimated 12 million tonnes; worldwide pork exports account for around 8 million tonnes; even if China bought up everything, it wouldn’t be enough to fill the gap. By the end of 2019 pork stocks are expected to fall by a further 50-60%. It will take years to get production back up to what it was because the stock of breeding sows has also fallen by around 40%. While pork consumption is down by 10-15%, the price of meat has risen by well over 100% in some cases. In Nanning, pork has already been rationed.

Share prices of China’s biggest pork producer have risen significantly because prices are rising, subsidies are flowing in and, in the wake of swine flu, the concentration of pig farms is being massively pushed forward.

Pork consumption also has a symbolic meaning. Since the beginning of the reform and opening up of the market, pork consumption has been systematically increased, followed a little later by milk consumption, so that everyone feels that things are moving forward and that their standard of life is getting better.

Culture war or Class war?

The Party itself continues to make propaganda of their construction of the affluent society. But the planners in Beijing have understood that they won’t really be able to surpass the USA. Their labour market policy since the stock market crash in 2015 is driving a privatisation of education and health, as well as a drop or stagnation in real wages, (partly through direct action against strikes and labour activists etc.)

On the other hand, nationalist propaganda and the pressure to make patriotic declarations of loyalty are on the rise, a trend that is particularly evident in the reaction to the protests in Hong Kong. State media portray the protesters as violent criminals and terrorists supported by foreign interests and spread memes that support the police, that can then be spread by avid users of social media. Mainly young, so-called ‘keyboard warriors’ support each other in setting up VPNs to overcome firewalls in order to launch joint campaigns in support of the police and against rebellious Hong Kong youth on the censored pages of Facebook and Twitter. Many celebrities and starlets, even Chinese rappers, join in. But the Chinese Communist Party cannot accept social movements – even nationalistic ones! When the controversial extradition law in Hong Kong was withdrawn completely and nationalists complained about it online, their posts were quickly deleted.

As ugly and alarming as this nationalist spectacle is, the question remains: behind the Chinese middle-class’ patriotic lip service, how many people are actually willing to make sacrifices for their country (especially if they live abroad)? Regardless of their expressions of loyalty, they will probably prefer to move wealth out of China if the Yuan continues to fall.

What is striking about the coverage of the “trade war” is how much emotion and personification is projected onto the two sides, not only in the propaganda but also even in the supposedly neutral analysis. ‘The USA is frustrated, the escalation is the result of disappointed confidence…’ The representation of countries as people, who feel, confide and decide like people, is deliberately distorting. Therefore, we have to firstly dispel some myths, which are also prevalent amongst parts of the left:

*The low wages in China are frequently explained by Chinese Maoists as the result of pressure from multinational companies. But their investments are now increasingly targeting the domestic market over production for export. Moreover, foreign capital represents only about one thirtieth of the investments in China. To attract foreign investors, opening the market and increasing transparency and legal certainty would be more important than wage repression. But this is the argument of the–

* democratic market reformers. The argument of those advocating a ‘democratic’ opening up of markets is that to attract foreign investment, market liberalisation, transparency and legal certainty would be the most important thing. They demand reform of state enterprises, rolling back high state taxes, privatisation, and “the end of the state’s grip on the economy!” The Chinese state owns around 27% of the total assets in China (slightly more than the annual GDP). During Mao’s time it was two thirds, but in comparison to Germany or the USA with approximately 0% after the deduction of state debt, there would still be some potential for privatisation. The people promoting market liberalisation are, of course, only thinking about their own pockets. They don’t seem to see that if state intervention and thus repression is reduced, they would be faced with stronger wage demands – and struggles to get them. This wage pressure from below would threaten to devaluate the state assets, which they intend to privatise.

* Maoists in the west and their anti-imperialist friends have talked for a long time about China’s status as a role model. Many even emphasise – against reality – how China is still socialist. Idiots like this lose their political significance. But many still refer to China as a pacifist alternative to US hegemony – another increasingly absurd position. Referring to the fact that Chinese companies’ profit margins are lower than their US competitors is just as misleading.

These Maoist arguments do not put the focus on the class antagonism within China, but point to a global antagonism between China and the West, and end up regurgitating the same arguments as the regime. But it’s not US customs taxes that are the biggest challenge for the ruling class in Beijing, but rising expectations of wage-earners in China, and the inability to meet these expectations with ever weakening profits.

China and the USA, like the rest of the world, are stuck in a deep crisis of over-accumulation, in which concentrated capital and available or potential productive capacity exceeds by far the strongest demand. The global slump in car sales and the enormous inequalities in income and assets are just two out of many examples of this. Trade disputes will – as we’ve seen over the last 15 months – continue to go back and forth because capitalists in both countries are trying to shift the disadvantages onto others. But the prerequisite for solving the conflict would be to solve the over-accumulation crisis. If new markets could be opened up overnight, offering everyone the profits of the boom years, then Trump and Xi would quickly come to an agreement. But such untapped markets don’t exist anymore. Another solution for over-accumulation would be the redistribution of wealth – or the destruction of capital in a trade war, or actual war.

In his long 1977 analysis, ‘Food, Hunger and the International Crisis’, Harry Cleaver worked out that the alleged 1970s ‘food crisis’ stood at the centre of international class struggle. The inability of the Soviet authorities to feed their own working class led to massive grain imports – in order to produce meat. (“The demands of Russian and Eastern European workers, to which the state had to respond, were not for more bread, but for more meat.”) The loans that had to be taken out for this purpose initiated the erosion of the USSR. This, in combination of Reagan’s strategy of ramping up the arms race in the 1980s, was the straw that broke the camel’s (USSR) back. Today, the problem for China is pretty similar: the working class has fought for a certain standard of living, which can no longer be financed with the ‘extended workbench of the world’ economic model. If we look at China’s investment into trade routes and raw materials, we can see a broader parallel with the USSR and their massive levels of investment into the development of Siberian oil in the 80s. Both follow(ed) a strategy of ‘self-sufficiency’ as a political goal, which is compounded in the case of oil by China’s high import dependency. Will swine flu deepen the problems? Will the military’s hunger for oil become their Achilles’ heel and armament once again the nail in the coffin?

With an offensive strategy, the Chinese government is trying to combine global economic, political and military influence with downward wage pressure and authoritarian social- and work organisation (state, management). This leads to a confrontation with the USA. Added to this is the attempt by the rulers in Beijing to reduce the level of wages and consumption through currency devaluation and inflation, to distract attention through promises of great power and propaganda, and to suppress resistance through censorship and repression and reduce cultural exchange with foreign countries. So far, the resistance of workers has put a certain brake on their endeavours. Wage trends show that they are not really getting away with keeping wages down. Although wage increases are lower than in the boom years, the gap with GDP growth has narrowed considerably. Wages are again growing more slowly than GDP, but the gap has narrowed sharply compared with the export boom years of the 1990s, particularly in manufacturing. Profit increases like we saw in the boom years would require a cap on wage increases of about 2.5% instead of 6.8%!

This would obviously require more drastic means than the suspension of minimum wage increases and the closure of workers’ NGOs. At this point the Chinese Communist Party faces a dilemma because it doesn’t dare use capitalist’s otherwise popular weapon of increasing unemployment.

The way out is sought through propaganda. Chinese media projects a picture of strength and self-confidence. Xi explains that we are well prepared for the trade war, state TV shows anti-American films and conjures up the spirit of the Long March. Many Chinese people I’ve spoken to don’t yet experience any direct effects from the trade war with the US in their daily lives. But put in perspective, the trade war is about all our working and living, housing and eating, health care, education, and so on. All this is directly and largely determined by the very politics that try to escape from domestic contradictions into the imperial confrontation. This confrontation is undoubtedly the worst decision for the people of China: even if you take the nationalist argument seriously that China must build and defend its power and independence against other – capitalist – countries. The reduction in real wages and bad health and education systems are the price that people should, according to the Chinese Communist Party, be willing to pay for building a domestic micro-processing industry. The vast majority of people in China (and in America) have nothing to gain from either domestic chip development or military armament, and are excluded from the political decisions that led to the escalation. Instead they would benefit from the redistribution of wealth.

The timing of this escalation was not chosen strategically according to when the Chinese economy and the military would be ready – possibly too early and too late for both sides at the same time – but was set by the internal dynamics. Faced with the end of the growth model and the expectations of a wage-earning class, the ruling elites have to either enter a foreign political confrontation now, or fail when it comes to solving their ‘domestic’ class contradictions. Perhaps Xi and Trump will fail on both fronts?

*****

Useful texts and links used for this article:

1 Michael Pettis, The Great Rebalancing.

2 On wages of migrant workers during this period, see http://people.anu.edu.au/xin.meng/Surplus_Labour_final2.pdf and people.anu.edu.au/xin.meng/wage-growth.pdf

3 https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2015/wp15151.pdf

4 Since wage increases are nominal and not inflation-adjusted, we must also compare them with nominal GDP growth. For wage growth, see: http://www.ftchinese.com/story/001071536/en

5 Victor Shih, China’s Credit Conundrum, New Left Review, Nr. 115, Jan. Feb. 2019.

6 https://www.theglobaleconomy.com

7 https://blogs.imf.org/2018/09/20/chart-of-the-week-inequality-in-china/

9 Tom Hancock, China’s regions hit by infrastructure spending downturn, Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/1eb6d9ac-be6e-11e9-b350-db00d509634e

11 China Labour Bulletin, https://clb.org.hk/content/migrant-workers-and-their-children

12 South China Morning Post, https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3008273/chinas-white-collar-workers-earned-less-first-quarter-2019

14 https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3012049/was-moment-us-china-trade-talks-fell-apart

16 Worker Empowerment, http://www.workerempowerment.org/en/publication/362

17 Kevin Lin, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2019/08/27/the-end-of-chinas-labour-reform/

20 https://clb.org.hk/content/pension-contribution-rates-employers-across-china-cut-16-percent

22 https://research.rabobank.com/far/en/sectors/animal-protein/african-swine-fever-affects-china-s-pork-consumption.html

23 Mindi Schneider has written about the role of increasing pork consumption in China extensively.

25 http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201812/27/WS5c24446fa310d91214051414.html

26 Harry Cleaver, Food, Famine and the International Crisis, https://libcom.org/library/food-famine-international-crisis-harry-cleaver-zerowork

27 https://www.forbes.com/sites/edhirs/2019/06/06/china-is-betting-big-on-increasing-oil-production