Reflections on ‘uneven and combined development’ and ‘class composition’

For PDF: UCD_CC1

From a perspective that puts the working class into the driver’s seat of social emancipation we find ourselves in a contradictory situation. During the last decades workers, as in people who have to sell their labour power to survive, have become the majority on the planet. When Marx, from his armchair, called for ‘workers of the world’ to unite, workers were actually a tiny minority globally, islands in a sea of independent artisans, peasants and forced labourers. Only today can we really speak of a ‘global working class’, but to the same degree that ‘being a worker’ has become a global phenomenon, ‘the working class’ seems to have disappeared.

Some people will jump to the conclusion that this invisibility is due to its lack of political agency, the fact that the working class doesn’t act as a conscious political force anymore. While this is true, it is tautological, meaning, it doesn’t answer the question of why workers seem to have lost the social and political cohesion to act as a class.

Other people react to this invisibility by stating that today’s working class is too fragmented to coalesce into a social force. They characterise the working class largely by the massive increases in informal employment, ‘over-educated’ unemployment, precarious jobs in smaller and often non-industrial workplaces and by being on the move between rural and urban areas or between countries. They write about patch-works and separation. But instead of acknowledging that their individual efforts to analyse such a vast a subject as ‘the global working class’ are reaching a limit, they invent new and fashionable categories, such as the ‘multitude’ or the ‘precariat’. However, our initial reaction to this point of view is primarily empirical. What about the massive growth in global industries and supply chains? Instead of atomisation we find a counter-current of industrial ‘concentration’ the re-forming of bigger workplaces – and the ‘industrialisation’ of labour in many sectors. Bank branches have been replaced by massive call centres, book shops by huge Amazon warehouses, small clinics by large hospitals and a myriad of small manufacturers by massive industrial complexes like Foxconn.

The idea that the world is dominated by ’surplus population’, which is largely excluded from value production, is equally flawed. Anyone who has a bit of insight into modern slum-economies will know that, for example, nearly half of US almonds are processed in slums in North India or that car part production reaches into Mexican shanty towns. Some point out that we now face a ‘working class north and south’, saying that the global north has pretty much been de-industrialised, while the south has become the new workbench of the world. On an empirical level, this is equally questionable. We can see that industrial centres or areas of marginalisation can be found in both halves of the globe. An analysis of anti-imperialism that is either based on the idea that certain areas operate as mere suppliers of raw materials or that certain areas gain extra-profits from unequal exchange with less developed regions makes less sense nowadays. Countries like China, Saudi Arabia and India would also have to be classified as ‘imperialist’ when it comes to the grab of minerals or land in Africa for example, and Sweden would be the world’s most imperialist country when it comes to gaining through unequal exchange.

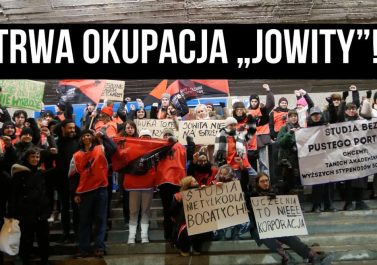

All this is not a question of who has the monopoly over the right way to interpret statistics. Questioning easy answers such as the ‘multitude’ or the ‘north and south’ divide purely through empiricism also remains limited given the fact that, despite the tendency for larger numbers of workers to come together in workplaces and across supply chains, the struggles we have seen do display a certain separation. Since the early 2000s we have seen street protests and square occupations that were led not by workers who were already organised in groups by working together in specific companies and sectors, but as the ‘precarious poor’ who criticise a repressive and corrupt state of austerity. However, we can still trace a ‘global strike wave’ in the background of these movements, primarily in the new industries in China, India, Brazil, but also in those countries where street protests and square occupations took place, such as in Egypt and Tunisia during the so-called ‘Arab Spring’.

This separation of ‘precarious poor on the streets’ and more organised workers’ struggles reflects real material divisions, not just a lack of political consciousness. Nevertheless, until they both come together, both sides will remained contained and burnt out. On the one side, the street protests were beaten within a political vacuum, as fighting the police, occupying public spaces or even toppling a government doesn’t solve the material problems of being an impoverished worker. On the other side, the strikes might have been able to enforce material demands and to impact on state power, but didn’t develop into a social focal point. Unlike in previous revolutionary cycles, the strikes didn’t develop to a scale where the interruption of production would show the wider working class that this production process could be taken over in order to change the whole way we organise our lives.

Furthermore, although protest movements erupted in various places simultaneously – most recently in Chile [1], Bolivia, Ecuador, Sudan, Iraq, Iran etc. – the movements largely remained focused on their national governments. Neither the ‘global condition’ of being a mobile, precarious worker nor the global integration of production alone seemed to have been a sufficiently cohesive force to link these movements internationally. [2]

The reaction of the left to these movements and their contradictory nature has been sketchy. Facing the challenge of developing political strategies to overcome the material hurdles for an international unification of working class struggles, many on the left seek to bypass these challenges by promoting an ‘electoral unification’ and a parliamentarian road towards gradual social change. We have written about the shortcomings of this strategy extensively [3]. Therefore, here it is sufficient to say that this strategy doesn’t take into account the fact that many of the recent working class movements erupted in countries of ‘21st century socialism’, where the left in national government was not able to overcome the structural constraints imposed by global capitalism, and in the process, weakened working class movements’ in terms of their independence and autonomy.

Another reaction by the left to the movements’ limitations is denial and the refusal to consider the necessity for strategic debate. Here we can distinguish three main tendencies: nihilist insurrectionism, meaning, we just have to fight harder and more ‘radically’; helpless programatism, meaning, we have to repeat our political message of working class unification until everyone gets it; and industrious ‘keep on organising’, meaning, we just have to work harder in our working class neighbourhoods and workplaces. For the few comrades who do try and understand what ‘the global working class’ actually is [4], the theoretical and conceptual framework seems inadequate to deal with the amount of empirical data and multiple facets of global working class lives and struggles today.

We have addressed some of these questions in the last chapters of our new book, ‘Class Power on Zero-Hours’ [5], but we want to use the fact that many of us currently have more time than usual to propose common work around the question of strategy. We suggest four main steps:

- Revisiting the only two genuine working class strategies that came out of the two revolutionary cycles 1917-1923 and 1967-1979: ‘uneven and combined development permanent revolution’ and ‘class composition’.

- Based on a better conceptual understanding we want to analyse the regional material differences and commonalities of recent movements in France, Chile, Sudan and the strike wave in China. We think that these four regions can serve as archetypes for the current composition of global capital and working class, representing different stages of development.

- In order to understand the challenges of a working class ‘take-over’ of the means of production under the current conditions we want to engage in a theoretical and empirical inquiry into a) the division of intellectual and manual labour and b) the (international) dimension of cooperation, for example in the form of subcontracting and supply-chains, in some of the essential industries, such as agriculture, energy, machine manufacturing.

- Finally, based on new insights into the material challenges for working class unification we want to discuss what an ‘international working class organisation’ could mean beyond having a common historical program. We want to discuss how such an organisation can be useful in practical and strategical terms and what a ‘Communist Program’ could mean in terms of measures, rather than demands.

These are big questions, so we are not in a hurry and we want to address them with as many comrades as possible. If you are interested in taking part in the debate, e.g. through Zoom meetings, drop us an email:

In the meantime, we start by making some points about the first point in the list above: revisiting the concepts of ‘combined and uneven development’ along with ‘class composition’. We do this in order to try and take what could be useful from both for a better conceptual framework to understand today’s increasingly complex situation.

———

1) Revising the concepts of ‘uneven and combined development’ and ‘class composition’

The history of working class movements throws up the more obvious material problems of unification, such as state borders, language barriers etc.. The underlying problem, which is often framed in political terms by nation states, but also finds ideological expressions in religious or other forms, is the unevenness of capitalist development and the subsequent divisions this creates within the working population.

During the early periods of capitalism, the unevenness of development meant that revolutionary movements had to find ideas and practices to unite smaller regions or sectors of (industrial) wage workers with the quantitative majority of poor artisans and peasantry or plantation labour under the colonial regime of slavery. The question also emerged of how workers’ struggles in less developed ‘despotic regimes’ could relate to more advanced working class movements in ‘bourgeois democracies’.

With the general development of global capitalism, uneven development largely expressed itself as a division between workers organised within industrial labour and workers in various conditions outside the industrial centres. Industrial workers more directly experience the collective nature of their work as well as the fact that social productivity under capitalism is turned against those who produce. This experience is less immediate amongst other workers, who will rather experience the stark levels of inequality, consequences of impoverishment, state repression or (domestic) marginalisation. To remain rather schematic, industrial workers will be more likely to develop a sense of collective social power and ideas to transcend the current way of producing, while workers who are more marginalised are more likely to focus on the need for wealth redistribution and/or (violent) confrontation with power structures. [6] As long as these two experiences remain separate, insurrections not only die, but the material conditions for the majority of workers are undermined.

While the unevenness of development has a political content and is managed by the nation states to a certain degree, it is largely determined by the capitalist process of accumulation and the class struggle within. The general tendency towards urban and industrial concentration creates the rural hinterland. Reacting to workers struggle by re-location and dismantling industrial strongholds creates the rustbelts. The general constraint to find more profitable conditions means that the patchwork of development and under-development changes constantly across the globe. This imposes both barriers and conflicting rhythms onto class movements.

Revolutionaries have been able to denounce the absurdity of development and productivity under capitalism fairly easily: gains in social productivity, for example, through the implementation of new technologies, lead to under-employment for many and exhaustion for those who have work. Under-employment puts pressure on wages, which in turn means that despite the potential to ‘work less and have a better standard of living’ workers work more and are relatively poorer – relatively in comparison to what the stage of development could provide us with, but often also relatively in comparison to previous generations. This is materialist propaganda that demonstrates that a better society is not mere utopia, but an actual possibility.

It is good propaganda but, to a certain degree, helpless. If the two poles of the revolutionary contradiction – an increase in social productivity on one side leads to an increase in relative poverty on the other – would meet in a single experience, the system would explode. The problem is that this experience is instead diffused within the global working class (meaning different groups experience it at different times and in different ways) and mediated by nation state measures and ideologies. This mediation by nation states in turn has become the focus of revolutionary ‘strategy’, in the form of anti-imperialism, Third-World-ism, national liberation movements etc.. By focusing on the level of the nation state, these ‘strategies’ have helped disguise the system’s underlying revolutionary contradiction.

Revolutionaries have been less prolific when it comes to forging strategies for working class movements to overcome the (regional) barriers of uneven development – beyond calling for all workers to unite in this or that organisation or peoples’ army. To put it bluntly, the movement has only brought forward two different strategies. Unsurprisingly, these strategies were formulated in the two main revolutionary cycles of the 20th century:

(1) Leaning heavily on previous works by Parvus/Helphand, the experience of the 1905 revolution in Russia in the aftermath of the military defeat against the Japanese army led Leon Trotsky to elaborate the concept of ‘uneven and combined development’ as the material basis for a ‘permanent revolution’. His main concern was whether a socialist revolution was possible in under-developed Russia and what significance the relation with workers’ struggles in the more industrialised European countries would have. Reflecting on the outcomes of the October Revolution in Russia in 1917 and the revolutionary upheavals in China in 1925 – 1927, Trotsky developed the concept further.

(2) The ferment for the social eruptions of 1969 to 1977 was the rapid industrialisation of northern Italy in the 1950s, along with the mass migration from the south and the new assembly-line based organisation of production that clashed with an established ‘skilled’ working class with deep historical experience of communist organisation. In their efforts to understand the relationships between the industrial cores in the north and the role of under-development in Italy’s south, as well as the new assembly line workers and a new generation of technical engineers, comrades around journals like Quaderni Rossi or groups like Potere Operaio developed the concept of ‘class composition’.

In the following we give a brief overview of both these concepts and their historical context. We then want to look at their similarities and differences and finally discuss to what degree they have use value under the changed global condition of capital and class today. We are not aware of similar efforts to contrast these two concepts historically, which primarily demonstrates how isolated the two political tendencies – Trotskyism and so-called ‘Operaismo’ – remained from each other, despite the fact that both concepts met a very similar fate once they were taken out of a revolutionary context and became floppy sociological and anthropological formulas.

* Uneven and combined development

Marx laid the groundwork for the concept of ‘combined development’. In 1847 he wrote (in his still ‘humanist’ fashion):

“To hold that every nation goes through this development [of industry in England] internally would be as absurd as the idea that every nation is bound to go through the political development of France or the philosophical development of Germany. What the nations have done as nations, they have done for human society.” [7]

Marx was acutely aware of the fact of how uneven development impacts on working class struggles. We can see this in his writings on the antebellum slave-holding economy in the southern states of the USA or on the significance of workers’ struggles against British despotism in Ireland for the workers’ movement in the colonial heartland. While these writings could still be interpreted as a mere endorsement of ‘national liberation’, devoid of class content, Marx went further in his exchange with the Russian revolutionary Vera Zasulich. In his letters he states the possibility of the remaining collective structures of the Russian countryside, the so-called Mir or Obchina, interacting with the revolutions in the advanced industrial regions of western Europe, where the best of two worlds could come together, and the Russian countryside could avoid having to go through the quagmire of capitalist development. The idea that different experiences or stages that exist within the class, such as advanced industrial development and forms of simple horizontal collectivity, can fuse and that something new could come out of it, is complex and was lost on many amongst the following generation of ‘Marxists’. Marx himself might have contributed to this, for example by depicting the development of capitalism in England as an archetype for the development of other nations in the Communist Manifesto.

At the beginning of the 20th century, with certain exceptions such as Kautsky or Luxemburg, the official leadership of ‘Marxist’ social democracy applied an insular analysis to the situation in Russia. They saw Russia’s general backwardness, the non-democratic form of the state and the predominance of semi-feudal relations in the countryside, only within the context of the confines of the nation’s borders. Thus, they came to the conclusion that Russian society would have to undergo further capitalist development in order to ripen for a socialist revolution. This analysis contributed to severe political and practical consequences. Plekhanov, the leader of Marxist social democracy in Russia, continued his efforts to forge an alliance with the ‘democratic bourgeoisie’, which weakened the revolutionary forces of the working class when these ‘democrats’ turned into reactionaries during the October Revolution. Leaders of the SPD in Germany could justify their support of the German war machine in 1914 by arguing that a war against the Czarist regime in Russia would help overcome the country’s backwardness and therefore constitute a step towards socialism. Apart from people like Parvus/Helphand or Trotsky there were not many voices which questioned this national and stagist point of view. Amongst the anarchists it were primarily those comrades who emigrated abroad who developed a wider horizon about the prospect of social revolution. Otherwise anarchism too didn’t manage to overcome the limitations of Russian social revolutionaries and their provincial view that the revolution would be centred on the peasantry and their alleged desire to return to the good old Russian ways of ploughing a field. In the best case scenario they would suggest a workers’ and peasants’ alliance, failing to address the issue of backwardness and isolation.

Two historical experiences led Trotsky to question official Marxism’s crude nationalist and stagist vision: the defeat of the Russia army by Japanese forces in 1905 and his participation in the 1905 working class uprisings in Russia. Japan won the war primarily due to the country’s industrial power that was able to produce a modern war machine. The rapid development of the local industry contrasted sharply with the general ‘backwardness’ of its state form. The his disconnect between state form and industrial development called into question the predominant view that each country would undergo the same gradual change from a feudal/monarchist-agrarian to capitalist/democratic-industrial social formation. The 1905 workers’ uprising in Russia’s manufacturing centres demonstrated that the objective tension between a developed industrial structure within a state, and an administrative structure still dominated by landed aristocracy, could create a revolutionary subjective opposition. Trotsky analysed Russia’s ‘uneven and combined development’ within the international state system it depended on.

He rightly pointed out the contradiction that the backwardness of the Czarist regime was, to a certain degree, fortified by international relations with the more developed states in western Europe. In order to secure its position in the state-system, from the early 1860s onwards the Czarist regime was forced to build a modern (arms) industry, being compelled by what Trotsky called the ‘whip of external necessity’. Given that the state was dominated by a landlord class that would oppose the taxation of an already under-developed agrarian sector, the industrialisation was primarily financed by borrowing foreign capital from France and other western nations.

“Historical backwardness does not imply a simple reproduction of the development of advanced countries, England or France, with a delay of one, two, or three centuries’, noted Trotsky: ‘It engenders an entirely new “combined” social formation in which the latest conquests of capitalist technique and structure root themselves into relations of feudal or pre-feudal barbarism, transforming and subjecting them and creating peculiar relations of classes” [8]

While intensifying the exchange and interdependence with the capitalist state-system, the industrialisation process also aggravated the internal tension within Russian society, primarily through the creation of a modern industrial working class. Industrial development in Russia had peculiar characteristics. It happened more rapidly, but more importantly, it jumped over the stage of small manufacturing and artisan production. This meant that industrial units in towns like St.Petersburg were on average much bigger and equipped with more modern technology than their western counterparts and employed workers who were, more often than, not thrown directly from the fields into a modern industrial production process. Furthermore, the concentrated new industrial working class was not as surrounded by ‘bourgeois institutions’ as its western counterparts. Skipping the artisan stage meant that traditional trade unions played less of a role in mediating and channelling workers’ initiatives. Apart from the fact that the economic structure didn’t support the development of a large middle-class, the Czarist regime had also suppressed ‘bourgeois freedoms’ and associations. The working class grew faster than their containment.

This structural power combined with the social outcomes of a debt-financed industrialisation process. In order to sustain it, the state needed to export grain in order to service its foreign debt repayments. When international grain prices fell, this led to greater pressure on the peasantry to deliver more grain without providing them with the means to increase productivity. Peasant unrests became more frequent and will have had their impact on the new peasant-workers. This situation exploded in 1905, when the new working class demonstrated that it could develop advanced political forms of organisations, such as the councils. Trotsky said that in Russia:

“The proletariat did not arise gradually through the ages, carrying with itself the burden of the past, as in England, but in leaps involving sharp changes of environment, ties, relations, and a sharp break with the past. It was just this—combined with the concentrated oppressions of czarism—that made Russian workers hospitable to the boldest conclusions of revolutionary thought—just as the backward industries were hospitable to the last word in capitalist organization.” [9]

The analysis of the objective factors – the international interdependency of the class relations in Russia, the ‘combined development’ of modern industry in an under-developed political framework and rural society – and his experience with the subjective expression during the 1905 uprising led Trotsky to break with the predominant social democratic position that Russia was only ‘ripe’ for a democratic revolution, not a socialist one.

“The vanguard position of the working class in the revolutionary struggle; the direct link it is establishing with the revolutionary countryside; the skill with which it is subordinating the army to itself – all of these factors are inevitably driving it to power. The complete victory of the revolution signifies the victory of the proletariat. (…) The latter, in turn, means further uninterrupted revolution. The proletariat is accomplishing the basic tasks of democracy, and at some moment the very logic of its struggle to consolidate its political rule places before it purely socialist problems.” [10]

He counteracted the argument that the industrial working class in Russia was numerically too small to lead a socialist revolution by breaking the national framework of thought. He maintained that Russia was the weakest link within the international state system and that a revolutionary insurrection of the local industrial working class could be a spark for an international chain reaction. Given the vast and under-developed rural hinterland in Russia, a socialist revolution there would necessarily depend on the revolutions in more developed countries in order to survive. The small core of urban industrial workers in Russia would need to connect to the developed cores in the west and use their support to build bridgeheads in the sea of Russian agrarian misery. Just as the global transition to industrial capitalism was uneven and combined, so too would be the further transition beyond capitalism.

We think that in this historical moment the concept of ‘combined development’ and its conclusions in the form of a ‘permanent revolution’ constituted the most advanced internationalist and working class political strategy. At this point of the argument any serious comrade would ask themselves if and how this ‘advanced position’ relates to the rather problematic, if not counter-revolutionary role Trotsky would later on play during the course of the Russian Revolution. Before the revolution he laid out the most basic measures workers would have to undertake.

“Abolition of the standing army and police, arming of the people, elimination of the bureaucratic mandarinate, introduction of elections for all public servants, equalisation of their salaries, and separation of the church from the state – these are the measures that must be implemented first, following the example of the Commune”. [11]

However, during the revolution, Trotsky would go on to become the prime mover in re-establishing a standing army and to reintroducing wage and managerial hierarchies within the factories. This article is not about the internal and external defeat of the revolution in Russia, but we wanted to raise this blatant contradiction for future discussions. At this point we limit ourselves to briefly describing the further progression and degeneration of the concept of ‘uneven and combined development’.

During Trotsky’s lifetime the revolutionary upheaval in China in 1925-27 seemed to prove the concept’s validity. Trotsky saw a chance here for working class political and organisational independence, based on the combination of rapid industrialisation and China’s increased interrelation with industrial powers, such as Japan. During the uprising, using the command over the Comintern, Stalin ordered the local Communist Party in China to subordinate its own organisation and demands to those of the bourgeois nationalists in the Guomindang to form an anti-feudal alliance for a ‘national revolution’. As it turned out, the insurgent but disarmed workers, who had formed councils in the industrial strongholds, and the Communist Party militants themselves, were slaughtered by their ‘progressive bourgeois allies’, who understood more about the revolutionary dynamic of workers’ struggles than the party leadership in the mother country of the international ‘Communist Movement’.

With the downturn of the revolutionary cycle after World War I the class content of the concept of permanent revolution became sidelined even within the Trotskyist movement. The focus was no longer on global production and trade and how they link the working class in regions of different stages of economic and political development. The theory turned into a schematic blueprint for revolution. It wasn’t surprising then that only a few revolutionary organisations were somewhat critical of the official representatives of the ‘national liberation and anti-colonial movements’ in the global south (Vietcong, Cuban revolutionary leadership) during the last global uprising in 1968. While being critical of the political leadership, the degeneration of the theory of permanent revolution meant that most Trotskyist organisations were not able to develop an independent practical strategy for the working class beyond calling for a ‘truly revolutionary leadership’. A working class strategy would have had to shift the focus from the political expressions of the uprisings to their material underbelly: how to connect the working class militancy in the industrial democracies, the industrial ‘socialist bloc’ and the small working class elements in the largely agrarian global south, in a phase where the global south was still largely a supplier of raw materials for manufacturing in the north?

By taking the concept outside its specific historical context, the explosive nature of the concept was defused. While political groups could use it as a blueprint for denouncing or encouraging political alliances, the declaration of ‘uneven and combined development’ as a ‘law of human history’ turned it into a ready-made formula for the academic field. Trotsky himself had facilitated this kind of appropriation by statements such as the following:

“The privilege of historic backwardness—and such a privilege exists—permits, or rather compels, the adoption of whatever is ready in advance of any specified date, skipping a whole series of intermediate stages. From the universal law of unevenness thus derives another law which for want of a better name, we may call the law of combined development—by which we mean a drawing together of the different stages of the journey, a combining of separate steps, an amalgam of archaic with more contemporary forms.” [12]

Today we can find thousands of anthropological and sociological articles in which the authors think they are saying something profound when using the term ‘uneven development’, merely to describe the fact that human societies influence each other.

Still, from a viewpoint that is searching for the possibility of international working class self-emancipation, the concept might still have a use value. More serious contemporary Trotskyists, such as Neil Davidson, question the attempt to turn the concept into an eternal law. Davidson states that the concept of ‘permanent revolution’ is only applicable to social situations where workers’ revolutionary struggle takes place under despotic non-bourgeois regimes and thereby contain both a democratic and socialist potential. In this sense the concept would be antiquated, unless extended to, for example, the relation between the anti-colonial struggles in Angola and Mozambique and the Carnation Revolution in Portugal in 1975. In this case, strikes and guerrilla activities in the colonies forced the Portuguese state to tighten the screw vis-a-vis the working class ‘at home’ in Portugal . The mobilisation and mutinies of largely working class conscripts to fight the anticolonial uprisings was the straw that broke the camel’s back, leading to the popular uprising that ended the dictatorship in Portugal. However, subsequent developments in both Mozambique and Angola (with the civil wars and ensuing dictatorships) calls into question whether there was actually a working class and ‘socialist’ core within the anticolonial struggle.

For Davidson the concept of ‘uneven and combined development’, while confined to capitalist societies historically, still has validity today. Let’s first see how Davidson argues why ‘combination’ only happens in capitalism:

“Until the advent of capitalism, societies could borrow from each other, influence one another, but were not sufficiently differentiated from each other for elements to ‘combine’ to any effect. In fact, it was the advent of industrial capitalism which initiated both ‘the great divergence’ between West and East, and—for the first time in history—the overwhelmingly unidirectional impact of the former on the latter which followed. As Rosenberg himself makes clear: ‘Imperial China sustained its developmental lead over several centuries; yet the radiation of its achievements never produced in Europe anything like the long, convulsive process of combined development which capitalist industrialization in Europe almost immediately initiated in China’ (Rosenberg 2007, 44–45). The detonation of the process of uneven and combined development certainly required sudden, intensive industrialisation and urbanisation. (…) ’In contrast to the economic systems that preceded it’, wrote Trotsky, ‘capitalism inherently and constantly aims at economic expansion, at the penetration of new territories, the conversion of self-sufficient provincial and national economies into a system of financial interrelationships’ (Trotsky 1974b, 15).” [13]

So what is the core of ‘combination’ then? We could summarise it as follows: Through the interaction within the global state and production system, certain states, which are generally less developed in terms of their political and administrative system, are forced, either economically or in order to stabilise their political regime, to introduce modern means of production in certain areas or sectors. This leads to a rapid transformation of the structure of the existing local working class, for example through new industrial concentrations or new means of communication. Struggles under these conditions have the potential to overwhelm the relatively unstable existing order, in particular if the ‘leap’ in development was achieved through dependency on (foreign) debt or a limited range of export goods, primarily in the form of raw materials.

Davidson provides some general examples where such a ‘combination’ plays a role today:

“We need not look far to find really striking examples of combined development today. In Saudi Arabia, a tribal system of politics has been grafted onto an industrialising society, so that the state, which owns the wealth of society, is itself the property of a 7,000-strong extended family of princes. The forcing together of the old and the new rarely comes in more extreme forms than this. And yet a significant fraction of the world’s energy supply rests on this peculiar political hybrid (and the events of 9/11 and after showed just how unstable and destabilising this hybrid could be).” [14]

This example might have more of a punchline if Davidson would add the fact that the local regime depends on millions of migrant workers from an array of Asian countries. Migrants even constitute the majority in some of the lower ranks of the state apparatus, for example many police officers are recruited from Pakistan. Their countries of origin either depend heavily on workers’ remittances and have been locations of recent civil war-type of situations (Nepal, Bangladesh) and are therefore relatively unstable, or rely on brutal political regimes to enforce local industrialisation (China, parts of India). Saudi Arabia is integrated into global exchange not only through oil, arms and finance. In countries like Sudan, investments from Saudi Arabia dominate large parts of the agricultural sector. The melting pot of migrant workers in Saudi Arabia, their massive significance when it comes to sustaining a despotic regime, the political tensions ‘at home’ could all turn into an explosive ‘combination’ of factors.

Davidson sees the urban working class in Al Alto in Bolivia as an example of the more subjective dimension of ‘combination’. He points out that the combination of having a large number of former miners with their experience of industrial organising settling down in town with already existing neighbourhood organisations has created the basis of a very politicised urban working class movement. This is indeed an interesting ‘combination’, but it doesn’t contain the dimension of international interdependence of both the state system and the production process as does the original concept. Similarly this example from South Africa, described in Beverly Silver’s ‘Forces of Labor’:

“For Mahmood Mamdani (1996: 218-84), the case of Apartheid South Africa provided a variation on the same theme. In 1948, with the victory of the Nationalist Party, South Africa abruptly shifted away from labor stabilization policies toward “the massive expulsions of Africans from cities and the vigorous policing of influx and residence” (Cooper 1996: 6). As a result, South African migrant workers, writes Mamdani, became “the conveyer belts between urban activism and rural discontent.” They “carried forms of urban militancy from the towns to the reserves in the 1950s” and then carried “the flame of revolt from the rural to the urban” in the 1960s, culminating in the 1976 Soweto uprising. In the decade after Soweto, the South African state was forced to move back to labor stabilization policies. It sought to “set up a Chinese wall between migrant and township populations” and to limit union organizing rights to resident urban labor while “tightening the screw of ‘influx control’ on migrants.” This boundary drawing strategy, in turn, helped turn a “difference” between migrant and resident urban workers into a tension-ridden “divide” (Mamdani 1996: 220-1).“ [15]

Another example Davidson uses in order to demonstrate the ongoing relevance of the concept is China:

“By producing the sudden rise of China as a great power, uneven development is driving a geopolitical revolution as the United States hurries to disentangle itself from Europe and the Middle East in order to concentrate on its famous ‘pivot to Asia’. At the same time, a new structure of economic interdependence has grown up that has already had major consequences for world development. As we know, from the 1990s onwards, China’s export-oriented model of development produced a tidal wave of cheap products that counteracted inflationary tendencies in Western economies. In addition, Chinese purchases of US treasury bonds helped to keep US interest rates lower than they would otherwise have had to be to finance the trade deficit. The net result of this was surely an extension of the global economic boom of the 1990s, and arguably much higher levels of sovereign and private debt when that boom finally collapsed in 2007–2008. The claim is not that China caused the crash. It is rather that international uneven development, with its deflationary effects and global trade imbalances, is a key ingredient of the economic crisis we are still living through today.” [16]

Here Davidson might stretch the concept of ‘combined development’ to such an extent that it ceases to describe more than the usual interdependency of nations within the world market, without being able to tell us more about the impact of (uneven) regional development on the class struggle. We will return to the question of how relevant the concept is when we contrast it with the discussions around ‘class composition’. The following quote from Davidson hints at the fact that both concepts are at least related:

“Take, for example, the Italian Mezzogiorno, where Italian unification was followed by a pronounced process of deindustrialisation, which led to a steady drain of capital to the North, with a long-term reservoir of cheap labour-power, cheap agricultural products and a docile clientele in the South; here the process of uneven and combined development led to similarly high levels of militancy to that seen in countries characterised by more general backwardness, the key episode being the revolt of the Italian in-migrants against their living conditions and low pay during the “industrial miracle” of the late 50s and early 60s. What is interesting about the Italian example, however, is that the process has continued, in different forms until the present day.” [17]

- Class composition

It is striking that Davidson uses the consequences of the rapid industrial development in post-war Italy as an example for ‘uneven and combined development’ when this development also became the social laboratory for the concept of ‘class composition’.

In Italy in the 1960s, comrades around journals like Quaderni Rossi and organisations like Potere Operaio tried to understand how the underdevelopment in the south of the country related to the rapid industrialisation in the north, and how this was not just an economic outcome of accumulation, but part of modern planned economic policies. They tried to understand how the experience of agrarian workers in the south with the landowners and their mafia informed their struggles once they had migrated to the north. They saw the assembly line as a weapon of exploitation that disciplined recently migrated workers from agricultural backgrounds and split them from the skilled workers of the old traditional socialist movement. They saw that the assembly line would turn into a means of communication of a new cycle of struggle, by generalising working class experiences from Turin to Liverpool and Detroit. The struggles in the core could develop a pulling effect right into the backwaters of the underdeveloped south, be it Sicily or Alabama.

Unlike the traditional Communist Party line – or current democratic socialist strategies – they saw the relation between a new generation of technicians (intellectual workers) and so-called unskilled (manual) workers not as one of an alliance between ‘workers of the head and workers of the hand’, which would basically enshrine the hierarchy imposed by the division of labour. Looking at intellectual’ and manual workers they saw that development and under-development, exists side by side within the same industry. Intellectual workers, such as engineers, have access to advanced social knowledge and technologies, whereas manual workers often use rather primitive tools. As long as this division of labour and developmental gap is not broken the working class could be pacified: the ‘intellectual workers’ would look for technical solutions to social problems and the manual workers would collectively reject, but not supersede the system of production. So instead of proposing alliances, the new comrades related to the working class background of a new generation of technical students, their feeling of alienation as intellectual workers, their double-existence as engineers with limited scope for creativity and as a managerial and supervisory force of the bosses. In turn they questioned whether modern industrial work was indeed ‘unskilled’ and purely ‘manual’ and discovered its social and creative dimensions, for example by pointing out how much modern factory production still relied on improvisation. Based on this they could propose forms of struggles beyond alliances between ‘intellectuals’ and workers. Their aim was to find forms which would undermine the knowledge hierarchy, like in common assemblies and political collectives. [18]

These comrades went beyond merely describing the differences and connections between various segments of the class, but they were looking for locations where struggles could lead to generalisation and organic class unity. Their hope was that the most advanced sectors, both in terms of social productivity and intensity of struggle, would be able to express the potential for a new society and radiate into the backward sectors of society.

Unlike the concept of uneven and combined development, the concept of class composition took Marx’s understanding of the ‘organic composition of capital’ as its starting point, rather than the international state system. The ‘organic composition of capital’ means the ratio in which capital brings together ‘variable capital’ (wages for workers) and ‘constant capital’ (raw material and machinery) in order to produce for profits. Marx pointed out that under the pressure of international competition on the surface level and class struggle at its core, for example the struggle of workers for a shorter working day, capital is forced to invest into machinery and other means to increase productivity. The ‘composition of capital’ changes permanently, primarily the share of ‘constant capital’ increases and the share of ‘variable capital’ shrinks. Official Marxism of the Communist Parties treated this process largely as an economic process or even as an ‘economic law’, with quasi natural characteristics.

Through Marx, the comrades around Quaderni Rossi rediscovered the political and antagonistic nature of this process – the class struggle within the seemingly ‘automatic’ process of capital accumulation. It is the struggle for higher wages and against the various ways capital tries to squeeze more work out of workers once their labour power is bought that is the prime dynamic forcing capital to change itself constantly. Workers’ collective power inside the production process has to be undermined by separating the work process into more ‘manageable’ chunks or by introducing new technology. Workers from new regions or backgrounds are hired to undermine existing collectivities. These changes of the composition of capital change the composition of the working class. In this way the comrades derived the concepts of ‘technical class composition’ and ‘political class composition’ from Marx’s ‘organic composition of capital’.

The concept of ‘technical class composition’ starts from the fact that we never face an abstract homogeneous working class. Workers are integrated to a larger, or lesser extent into the immediate production process. Within the production process workers cooperate more, or less, directly with each other. Depending on the sectors they work in or their specific qualifications their individual and/or collective power differs. The ‘technical class composition’ expresses capital’s main internal contradiction: in order to increase social productivity capital is forced to allow workers to cooperate as closely as possible – but a close cooperation of workers is dynamite in the belly of the beast. Workers use their productive and collective power to question the power and rule of capital. They ‘re-compose’ themselves politically, by finding new forms to struggle under given conditions; these struggles radiate within the wider working class and give rise to new political ideas about social emancipation. The comrades analysed the relation between particular forms of how exploitation is organised and how workers struggles unify and develop a political social vision as the relation between the ‘technical class composition’ and the ‘political class composition’.

Their research went beyond the contemporary production process and into history. [19] They were able to distinguish, for example, how a ‘technical class composition’ based on integrated industries and skilled workers in the early 19th century formed the basis for a ‘political class composition’ in the form of the revolutionary council movement: skilled workers knew that they can run integrated industries directly, and industries were often located close to the urban areas. This combination was the ground for a ‘councillist’ form of organisation and vision of social emancipation. The comrades saw that apart from brute state repression, it was the assembly line production and labour migration that undermined the ‘political composition’ of the skilled workers. The technical composition of the ‘mass worker’ of their own era – largely ‘unskilled’ workers in the factories for consumer goods – developed different forms of struggle and a vision of ‘communism’ that was more characterised by the refusal of work through ‘socialisation of work’ (“we all work, we all work less”) and a critique of empty individual consumerism than by the skilled workers’ ‘self-management’ of production during the council movement. Or to say it in the often more pompous words of Operaismo, Battagia in this case:

“The scope of analysis was the bond between bodies and instruments of labour, between workers’ outlooks and behaviours and the form of production. Between subjectivity and objectivity. This showed that the political behaviours, forms and needs expressed by the class struggle are materially shaped by the objective relation between labour and capital. Thus while the professional [skilled?] worker – faced with a merely formal subsumption of their labour by capital – struggled to re-appropriate the means of production and self-manage the factory, the mass worker struggles directly against the materiality of capital, its technical way of being, expressing a now real subsumption of work. According to this formulation, the revolutionary process is swayed by the class figure which tends to dominate in the capitalist organisation of work. The technical class composition specifies that section of the working class on which capital bases its accumulation, while the political class composition specifies the materially determined characteristics of class antagonism.” [20]

For these comrades the concept of class composition was not a sociological tool, but a strategic weapon. By analysing the objective and subjective factors they tried to anticipate which sectors or areas could prove as the new ‘weak links’ in the command of capital and radiating centres that could aid the unification of the class. The position of a ‘vanguard’ was less defined by supreme political consciousness, but by objective conditions of ‘centrality’ workers find themselves in. Acknowledging the central role of ‘the factory’ in the unification process of the class didn’t mean to ignore the rest of society, but trying to understand the links, e.g. in the way female factory labour gave boost to an independent working class women’s movement or the way the factory re-structured the sphere of domestic labour. A decade later Battagia reflects on the struggles in 1969:

“In our case, a section of the labour force made materially homogenous by a particular relationship to capitalist technology (the assembly line) and a consequent political behaviour: the demand for wages as income, the refusal of work and sabotage. It was precisely this homogeneity which allowed the working class of the Hot Autumn to become a “class composition”, drive the revolutionary process, impose its struggles onto society and force a profound revision of the traditional theoretical apparatus of class struggle. All of this was made possible by the powerful link between an objective fact (material conditions of exploitation) and a subjective one (political behaviour). The mass worker was a section of the class which could be recognised with extreme precision, which could be exactly quantified and from which driving political objectives could be identified with relative immediacy.” [21]

The notion of ‘centrality’ is essential for the concept of class composition, but that doesn’t mean that the comrades of Operaismo didn’t look at and recognise the importance of the relation between centre and periphery, for example between ‘the factory’ and the international context. One of the prime texts is Alquati’s ‘Capital and working class at Fiat: A centre within the international cycle’ in ‘Sulla FIAT e altri scritti’, written in 1967, a text that has never been translated into English. We rely on the German translation [22], but think it might nevertheless be interesting to summarise some of Alquati’s notions of the ‘centre’. He looked at the metal sector and describes its central position within the capitalist cycle.

The metal sector is the only sector which produces both the means of production adequate to the capitalist form of production, which is machinery, and commodities dedicated for consumption. This means that within the production cycle and the cooperation of the metal sector the combination of the collective worker takes place on a very extended level.The division of labour has a degree of sophistication which we usually only find on the level of the wider social division of labour. Alquati meant that within the metal sector we find all sorts of labour combined: intellectual (engineering and planning), skilled (technicians, mechanics), unskilled manual (assembly, maintenance), service (marketing) etc.., often in close spatial proximity, but also extending into society, such as the university departments. These things are significant if we want to know how workers can not only ‘fight capital’, but combine their various knowledges and abilities into a ‘creative’ revolutionary force that can reshape the way we live.

The fact that the metal sector combines the production of both means of production and consumption and that some companies exchange both between themselves also means that, historically, this ‘closed circuit’ created a specific dynamic which turned the metal sector into the driving force of mechanisation in society in general. Mechanisation also meant that factories of companies like FIAT became magnets for the rural-urban migration from the ‘backward areas’, through exploitation of ‘peasant-workers’ labour. In countries like England, France and Germany, this happened on an international scale. We can find the most complex and (internationally) extended form of cooperation within the metal sector, which meant that it became the sector with the largest and most intertwined workers’ concentrations. Alquati observed that the global integration of markets (FIAT exported trucks, tractors, diggers and military vehicles etc. to the so-called Third World early on and had a major impact on local markets) was now intensified by the global integration of production (FIAT had particularly close links with governments and engineering administrations in the so-called Eastern Bloc, to set up factories there). FIAT not only sold commodities to the so-called Third World, the company transferred productive/destructive capital in the form of ship engines, gas turbines, fighter-jet parts and manufacturing machinery.

The metal sector in general and the automobile sector in particular subsumes other ‘raw material processing sectors’, such as rubber, glass, plastics, oil, dominating whole national economies in the global south and connecting industrial with mining and plantation labour. These are ‘strategical raw materials’ and the trade and production relations immediately have a political dimension in the form of trade agreements between states, but also determining the policies of development departments and even military strategies. Alquati urged an analysis of the ‘relation between simple and complex labour on an international level, taking into account the different facets of technology and productivity. This in turn would have to be related to the reproduction costs in various regions.’

The text goes into much more depth and detail, but we can read it as a call to see the social and international dimension of companies like FIAT as a battle plan through which the working class can re-unify its political struggles internationally. The text was written before the major strikes at FIAT in 1969 and anticipated their social significance.

Still, the Alquati text can be taken as further evidence that the Operaismo comrades largely believed that the working class can overcome the divisions set by the uneven development and state system through the fact that the extended cooperation within the social production process can serve as lines of communication and veins for workers’ struggles. This seems understandable in a historical situation like post-war Italy where the integration between industry, society and state(-planning) was exceptionally dense. We are not aware of many texts from that era that would look at the wider global situation and its unevenness in development from a perspective of ‘class composition’. This will also be due to the fact that the Italian radical left’s main framework to think and debate ‘international relations’ was Lenin’s text on ‘Imperialism’ [23], while the Trotskyist left had minimal influence in Italy. This dependency and over reliance on Lenin’s concept is reviewed critically by Ferrari Bravo, an Operaismo comrade, in 1975. The text was translated recently by comrades around the Viewpoint Mag. Their introduction sheds light on the background of Bravo’s text:

“Before this essay, Ferrari Bravo had distinguished himself within operaismo by bringing his political perspective to bear on the margins – not only to the peripheral neighborhoods of Italy’s northern industrial triangle where southern Italian migrants lived, but to changing dynamics within the South itself. In “Forma dello stato e sottosviluppo” (“Form of the State and Underdevelopment”), Ferrari Bravo analyzed the partial industrialization of the South through the state’s Cassa per il Mezzogiorno (“Fund for the South”) as a political response to the increasing mobility of labor-power. This “plan” of reforms was designed to integrate cycles of workers’ struggles into the productive cycle of capital. In “Old and New Questions in the Theory of Imperialism,” Ferrari Bravo elaborates this research within the expanded frame of the world market, harvesting what he deems useful from Marx, Lenin, and subsequent theorists to develop a rigorous analysis of his current conjuncture. (…) Rather than mine the written records of Lenin’s 1917 intervention for scientific concepts – Ferrari Bravo suggests abandoning the categories “labor aristocracy” and “parasitism” to the gnawing criticism of the mice – instead he looks to Marx for a methodology and framework within which to pose this political question anew.” [24]

Bravo starts by briefly summarising the main chain of thought in Lenin’s ‘Anti-Imperialism’: monopolisation of key industries in the global north; shrinking capacity of domestic markets to absorb output; accelerated flight into finance; capital export to the south and colonies where the main exploitation now takes place, in particular in raw material processing; global value transfer finances social peace in the north, and with the help of the trade unions local workers become increasingly ‘aristocratic’. He writes:

“Finance capital as hegemony of a banking oligarchy, of a class oriented to speculation and to income; capital export as swelling of social strata (even workers) who live by clipping coupons; imperialism as contradictory system of global domination on the part of a handful of rentier-states: this series of definitions specifies the theoretical and political axis of the popular outline.” [25]

He then criticises Lenin’s assumption:

“Here a rigid stagnationist interpretation prevents one from seeing, behind the falling rate of profit, the increase in the mass of profit; behind financial centralization, the enlargement and the real transformation of the industrial base that result from the great wave of “heavy” industrialization, which emerges between 1800 and 1900 in Europe and the United States, and of which the colonial partitioning is obviously an integral moment. And, on the other hand, conversely, the export of capital to the colonial world is well short of having the role that Lenin attributes to it, of propelling capitalist development to the periphery – this recognition will become one of the central themes of the subsequent literature on imperialism, oddly enough even for those who hold firm to the Leninist interpretation on the whole.” [26]

Bravo basically says that Lenin’s idea that production is just shifted to the south is too simplistic and that we have to understand the process as a more complex expansion and specification of industries on a global scale. Bravo continues by pointing out that Lenin’s (mis-)understanding of imperialism as being merely ‘parasitic’ and not a conflict-ridden process within the state system to restructure the global process of production and exploitation results in Lenin’s simplification about how the emerging global working class is divided into ‘labour aristocracy’ in the centre and ‘super-exploited’ workers at the periphery. Although not explicitly mentioning both of these concepts, we can see read an approximation of ‘uneven and combined development’ and ‘class composition’ in the following paragraphs:

“The “stratum of workers-turned-bourgeois, or the ‘labour aristocracy,’ who are quite philistine in their mode of life, in the size of their earnings and in their entire outlook,” [Lenin] is the strange fruit of the vast process of the concentration of production, of the increase of the scale of accumulation which also underlies and continually feeds the imperialist transformation of the system; and it is the extraordinary counterpart to the Leninist model – on which he gambles his entire political “career” – of the leadership [direzione] of the massified worker over the entire revolutionary process in the Russian subcontinent, in any case, of his holding fast to the workers in the factory, to their compact organization imposed by the very mechanism of the capitalist organization of work. (…) It should be noted that behind this lies a material mismatch [sfasamento] in the levels of global capitalist development that does not get posed as an explicit theoretical problem. (…) It is perhaps granting too much cunning to history and to Lenin’s own political intuition to project his dismissive judgment of the “aristocracies,” branded as a mere phenomenon of trade-union opportunism, onto these outcomes. But the fact remains that, on the theoretical terrain, in Imperialism this concept plays the role of falsely projecting onto capital those things which are clearly contradictions, limits, and delays of the organization of the class within the “advanced” areas of development – and, consequently, of reducing potential but actual phenomena of “integration” to the level of a merely ideological mechanism. But, even before that, the concept also “removes” contradictions and limits in the contemporary [for Lenin] Marxist theory of development. The tension – which is essential in Lenin, which is Lenin – within a general theoretical axis oriented in the direction of an insurmountable anarchy of capital, between the project of the party as a project of planning [progetto di piano] and the given possibilities of capitalist development in that phase, reaches the limit of its vitality. There the entire “collapsist” [crollista] tradition is renewed, for the first and last time, in the revolutionary sense – the war itself is, in fact, Zusammenbruch politics in action.” [27]

[add current situation]

A lot of heavy sentences, which boil down to a few basic positions. Firstly, that ‘uneven development’ and its divisive impact has not been analysed sufficiently from a working class perspective and the concept of ‘labour aristocracy’, which Lenin uses to describe these divisions, is too hinged on the ‘ideological abilities’ of a parasitic capital to integrate certain segments of the global class. In doing so, you undermine the potential for development in the south and gloss over the complexities of the working class in the north. Instead we would have to see this as a contradictory process of ‘class composition’. To be honest, it still remains rather abstract. But we found another little hint in this text which helps us to think about the relation between ‘uneven development’ from a ‘class composition’ perspective:

“This structure of international trade, therefore, rewards capital that has already reached – that has already been compelled to reach – the phase of exploitation in terms of relative surplus-value, and simultaneously it outlines an international division of labor that fosters, at its edges, the most exacerbated tensions of the method of extraction of absolute surplus-value. And so how far we are, even in the sharing of presuppositions, from the idyllic framework of international specialization offered by the theory of comparative costs!” [28]

Let’s remember the conceptual origins of ‘class composition’. The external and internal pressures, primarily the struggle of workers for higher wages and against the imposition of work drive capital into development. ‘Development’ expresses itself in a rising ‘organic composition’, meaning primarily, the increase of productivity by investing into machinery. Marx calls this intensification of exploitation the increase in the production of ‘relative surplus value’. But this process is not a one way street. A rising ‘organic composition’ of capital results in a lower rate of profit, which means that in a counter-move capital tends to get invested into areas or sectors with a ‘lower organic composition’, where exploitation is increased through ‘absolute surplus value’, meaning primarily through longer working hours. Here we can see that ‘uneven development’ – sectors which use the newest technologies next to labour intensive sweatshops – are not a sign of ‘backwardness’ or lagging behind, but actually express an outcome of ‘capitalist development’.

Before we look at both concepts together, we want to point out briefly that once taken out of the context of the revolutionary moment it was born in and superimposed over history, the concept of ‘class composition’ experienced a similar fate to ‘combined development’. The first phase of conceptual degeneration was ushered in by the limits of class struggles in the late 60s themselves. The 1968 uprising touched all spheres of working class life, from welding departments to the bedroom, but given the complex and dispersed nature of social production, the movement didn’t develop a clear vision of what a takeover of the means of production could look like. The shortcoming of the comrades who developed the concept of class composition was that they ended up either theorising this as a strength of the movement, for example by glorifying the ‘against work’ attitude of the struggles, or by trying to create a conceptual shortcut. Shortcut meaning that ‘class composition’ became a slogan of political vanguardism and adventurism: “the ‘technical composition’ (the material constitution of the social production process) doesn’t allow the class to recompose, so we have to recompose the class from above by leading an (armed) attack at the heart of the state.

One of the best known and few attempts to understand the ‘class composition’ after the downturn of the mass workers movement was Sergio Bologna’s text ‘The Tribe of Moles’, written in 1977. [29] In it he tries to ‘uncover the new class composition’ of the 1977 urban rebellion, comprised of unemployed youth, women’s groups, students, and workers in small factories. His text is a role-model in ‘materialist analysis’ of an otherwise diffused movement. So he looks at the new ‘party system’ of crisis, which is politically tied to international institutions such as the IMF and economically to the massive growth of suburban real estate. He criticises the left for focusing on the state as ‘politically autonomous’, while ignoring the fact that the state slowly erodes workers’ autonomy in the factories. He traces the connection between changes within the university, the new struggles of ‘precarious white-collar’ workers and the politics of ‘subjectivity’ like the feminist movement, but ends with a call to see the ‘new class composition’ in wider terms: “but once again we must go beyond the University, both as a base for the movement and as a point of aggregation, in order to identify the channels that can bring about a mobilisation of the entire mass of disseminated labour.”

Most comrades ignored this call to re-engage in materialist analysis and either retreated, or accelerated the ‘political and armed attack’. This was the immediate phase of degeneration and despair. From then on, the concept of ‘class composition’ was pretty much stripped of its inner cohesion and political content, namely the concentration and cooperation of workers, which predetermine the self-organisation of the class from its central core. Similar to ‘uneven development’, the concept became a sociological projection screen, merely describing the different backgrounds of workers or the structure of certain sectors without looking at the wider question of political unification. In the case of people like Negri, this ‘sociological’ element of the concept only served as a flimsy empirical layer on which to build ever more fashionable political ideas, in the form of the ‘social worker’, the ‘immaterial worker’, the ‘multitude’ and so on.

There is still a fair bit to learn from the theoretical and practical work of the comrades back then, but times have changed. While it might have been a cultural challenge for workers in the north of Italy to deal with newcomers from the south, today migration is a much more global phenomena. While assembly line workers and technicians might have gone to the same schools together, today we see a global division of intellectual and manual labour that is separated by larger geographical spaces. We have software programmers inSilicon Valley and Bangalore used for car plants and Amazon warehouses in Alabama and Foxconn plants in China. The ‘metal sector’, which combines the complex work of both machine engineering and long-lasting consumption goods like the car, has lost in social centrality, but not been replaced by a sector with equal qualities. These differences are obvious.

- ‘Uneven development’ and ‘class composition’ – two historical concepts

How do we begin to map out a conceptual framework to analyse these current complexities? We could proceed by looking at four main questions to evaluate the validity of these two concepts:

1. To what extent are the two concepts defined by their historic period and location? to what extent are they primarily describing different stages in general development of the capitalist system?

2. What is the shared perspective of the two concepts? Where do they describe the process of working class unification, albeit from different perspectives, which themselves are not reducible to the differences in the historical period in which the concepts emerged?

3. What are the political disagreements between the two concepts, beyond the question of difference in historical perspective?

4. What are complementary elements of the concepts which could still help us to think through the current empirical jungle which is the global working class?

The concept of ‘uneven development’ originated in an overall situation where many nation states were still defined by aristocratic or colonial regimes, but more importantly, by relatively low levels of industrial intertwinement and exchange. Under these conditions ‘combination’, the introduction of modern methods of exploitation of mass labour in an otherwise relatively backward regime, had a more explosive effect. Four decades later in western Europe, the state-system and industrial structure had become much more integrated. We saw (international) state departments coming out of the Marshall Plan and the Breton Woods Agreement, which engaged in monetary balancing of productivity increases and wage pressure or the drawing up of regional industrial investment plans. Instead of having a few ‘islands of development’, like the industrial areas of St. Petersburg, factory labour had penetrated much deeper into the social fabric and formed integrated clusters. These different stages of development partially explain why ‘uneven development’ focuses more on the relation between working classes within the nation state and ‘class composition’ more on the antagonistic constitution of the working class within the international process of production and exploitation. In these ways we can see that the concepts are clearly products of their times.

But this difference in perspectives also reflect different political outlooks. Unlike Marx, Lenin and Trotsky never really understood or appreciated the political nature of the production process – and therefore the material basis for workers’ self-organisation. For them the ‘revolutionary nature’ of factory work primarily consisted in the ‘disciplining force of the work process’ and the mere quantity of workers brought together under one roof. They were less interested in how the working class organised itself concretely, but how workers struggles could be manoeuvred on the global map of class war.

At the same time the concept of ‘uneven development’ hints at shortcomings in the analysis of the Operaismo comrades to envisage an international revolutionary process beyond ‘spreading strikes’ and wage demands within an integrated industry. The concept of ‘uneven and combined development’ tells us more about the different ways a ‘communist political program’ would be articulated in different regions, depending on their different levels of development – and the challenge to find ways of unification. Some poeple say that ‘Operaismo never solved the organisational question’. A partial explanation of the fact that the comrades never developed models of ‘associational power’ is because they focused too much on the strong organic links within the immediate production process as the main arteries of workers’ organisation. This unifocus led to a lack of conscious organisational structures that could bridge the gaps between industry and the periphery of the class. It is therefore not surprising that when confronted with a complex global situation with patchy industrial links, many Operaismo comrades fell back on a simplistic anti-imperialism (a la ‘United front of Detroit and the Vietcong’).

What both concepts have in common is that they base their political proposals for the working class on strategies that invert the development of capital into working class organisation and power. The concepts are based on ‘centres’ and ‘development’. This poses material limits for their crude application in the current situation, which is not characterised by clear ‘central sectors’ or rapid industrial developments in otherwise backward areas. Does that mean that we have to discard these concepts and, like many comrades do, portray the current structure of the global working class as an undistinguished empirical mess of atomisation? It might sound eclectic, but we think there are certain elements of these concepts that could be tested by applying them to analyse contemporary class movements that take place under different conditions of regional development. So for example, we could undertake a comparative analysis of current protest movements in France, Chile, Sudan and China, like we proposed in the introduction.To quote Mike Davis, whose analysis can often be too crude and apocalyptic, but still a step forward in the debate:

“At a high level of abstraction, the current period of globalization is defined by a trilogy of ideal-typical economies: superindustrial (coastal East Asia), financial/tertiary (North Atlantic), and hyperurbanizing/extractive (West Africa). “Jobless growth” is incipient in the first, chronic in the second, and absolute in the third. We might add a fourth ideal-type of disintegrating society whose chief trend is the export of refugees and migrant labor. Contemporary Marxism must be able to scan the future from the simultaneous perspectives of Shenzhen, Los Angeles, and Lagos if it wants to solve the puzzle of how heterodox social categories might fit together in a single resistance to capitalism.”

[30]

‘Class composition’ can tell us something about the (potentially) already existing organisational structures of the local class and about the need for ‘associational power’ to bridge gaps in the productive social fabric. ‘Uneven development’ can tell us more about how, for example, the wage demands of wildcat strikes in China and the protests against a corrupt regime and fuel price hikes in Sudan, where China holds majority assets in the oil industry, might ‘combine’ into more than just the sum of their parts. Unfortunately there are only a few current efforts to analyse the global working class beyond empirical description. Beverly Silver’s frameworks of ‘technological, product, spatial and financial fixes’ and ‘workplace bargaining and associational power’ are useful crutches, but remain too descriptive and focused on the ‘shifts in developmental centres’ rather than on the question how struggles under conditions of development and under-development could combine:

“Our analysis of the globalization of mass production in the world automobile industry in Chapter 2 concluded that the geographical relocation of production has not created a simple race to the bottom. Rather, we found a recurrent pattern in which the geographical relocation of production tended to create and strengthen new working classes in each favored new site of investment. While multinational capital was attracted by the promise of cheap and controllable labor, the transformations wrought by the expansion of the industry also transformed the balance of class forces. The strong labor movements that emerged succeeded in raising wages, improving working conditions, and strengthening workers’ rights. Moreover, they often played a leading role in democracy movements, pushing onto the agenda social transformations that went well beyond those envisioned by pro-democracy elites.” [31]